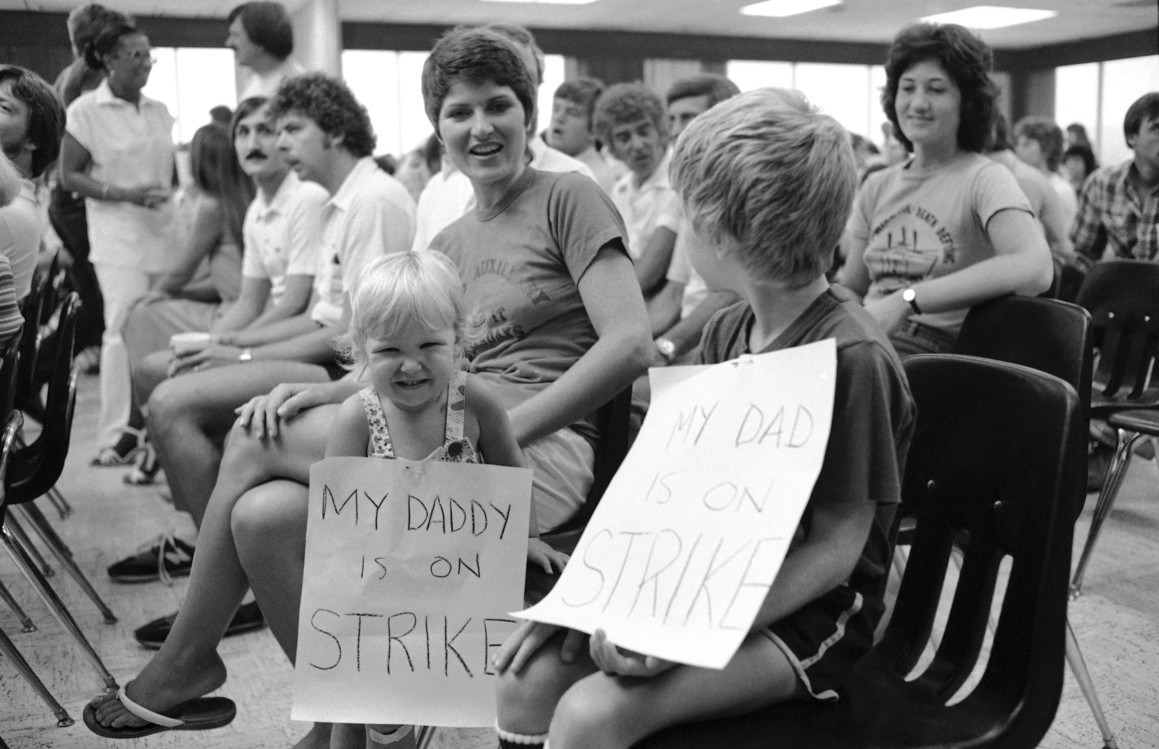

Above Photo: Members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization picket outside a Federal Aviation Administration air route control facility in Leesburg, Virginia, on Aug. 5, 1981. Budd Gray/AP Photo.

This week marks the 40th anniversary of an illegal strike by the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) that was decisively broken by President Ronald Reagan. That strike began on August 3, 1981, when more than 12,000 air traffic controllers employed by the Federal Aviation Administration went on an illegal strike after their negotiations with the administration failed to produce an acceptable contract offer. Within hours, Reagan appeared in the White House Rose Garden, flanked by Secretary of Transportation Drew Lewis and Attorney General William French Smith. If the strikers did not return to work within 48 hours, he announced, they would be “terminated,” fired and permanently replaced. The vast majority of strikers defied his order, and at 11 AM, Eastern time, on the morning of August 5, they were fired.

In my book, Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers and the Strike that Changed America, I told the story of this event, the most ambitious and expensive act of strikebreaking in U.S. history, one that I believe marked a turning point in American labor relations.

On this particular anniversary, I can’t stop thinking about a photograph I included in the book: an image of striking controllers who gathered for a rally at Eisenhower Park on Long Island on the morning they were to be fired. Reporter Jimmy Breslin attended and described how, as the strikers gathered, a federal marshal appeared and handed out copies of the federal injunction that ordered them back to work. They drove him out, chanting “We want a contract.” When the 11AM deadline for their compliance approached, the controllers and their families held hands and formed a large circle. Breslin was amazed to see “members of suburban white America,” as many of them were, and military veterans (as most controllers were) gather to defy the law in this way. At “the moment they were supposed to be fired on order of the President of the country,” he reported, “their right fists shot up in the air” in what Breslin called a “Stokely Carmichael salute.” These folks might be from middle America, Breslin wrote, yet that morning they “were perhaps the only people in the country with the courage to oppose the established order.”

The picture was taken just before the circle formed. It shows black and white controllers and their families bedecked with union buttons, proudly holding their picket signs and an American flag aloft, wearing tee shirts emblazoned with the slogan, “PATCO: leading the nation with striking results.” They gathered behind an unfurled bright yellow Gadsden “Don’t Tread on Me” flag, held like a banner between two kneeling strikers.

We saw the same flag at another turning point event this year, on January 6. The “Don’t Tread on Me” flag was quite prominently displayed during the violent assault on the Capitol that afternoon. In fact, the flag was so ubiquitous during the insurrection that one appalled newspaper columnist immediately took his flag down off the wall of his office where it had hung for years.

Created in 1775 by South Carolina politician and slave holder, Christopher Gadsden, the flag had played a prominent role in the American Revolution. “For most of U.S. history, this flag was all but forgotten,” writes graphic design scholar Paul Bruski. It began to make a comeback after the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976 (which might account for PATCO strikers deploying it 5 years later). Over time, though, it began to develop “some cachet in libertarian circles,” observes Bruski. Then the Tea Party of 2009 thoroughly embraced it, and it has been a constant presence at right-wing rallies since.

On January 6, the “Don’t Tread on Me” flag signified something very different from what it had stood for in Eisenhower Park 40 years ago. The contrast has me thinking about the sources and goals of social conflict, the meaning of solidarity, and the terrible toll these past forty years have taken on this country.

A good part of the damage has flowed from what workers lost after the PATCO strike: a robust capacity to come together to engage in effective collective actions to make demands of their employers. In other words, the ability to strike.

When PATCO strikers formed their circle in Eisenhower Park, U.S. workers still frequently and confidently wielded that elemental tool of working-class agency. During the 1970s, workers staged an average of 289 major work stoppages (involving at least 1,000 workers each) annually, slightly higher than the average of 283 during the 1960s. Workers’ ability to strike played a key role in keeping wages in line with rising productivity. Not surprisingly, when the relationship between wages and productivity began to slip in the mid-1970s, with wages lagging productivity for the first time in the postwar era, this slippage coincided with a dip in the annual average of major work stoppages, which was fell to 251 in the last three years of the 1970s. But after Reagan broke PATCO, that slow erosion became an absolute freefall.

Strike militancy declined more rapidly in the 1980s than in any other decade. Corporate America made sure of that. Inspired by Reagan’s bold action, a slew of private sector employers, including Phelps Dodge, Hormel, and International Paper, took advantage of the restructuring economy to provoke strikes and then hire replacement workers to force unions into big concessions. As workers sensed how dramatically the balance of power was shifting, the annual average of work stoppages plunged to only 35 per year in the 1990s. But the slide didn’t stop there. In the 2010s the average was 16, and there were only 8 in 2020.

The PATCO strike isn’t responsible for the entirety of this falloff, of course. A variety of other structural factors contributed to the long-term decline of U.S. strike militancy. Yet that pivotal strike provides an historical milestone against which we can measure the costs of U.S. workers’ loss of the ability to defend their interests through collective action.

One measure is financial. If workers’ wages had kept up with rising productivity during the past 40 years, they would be earning on average $10 more per hour, the Economic Policy Institute recently estimated. The explosion of income and wealth inequality that has been eating away at the foundations of our politics and culture would have been substantially arrested had workers been pocketing that lost money over the past four decades.

Yet dollars and cents alone can’t measure what’s been lost. The undermining of workers’ strike power also disabled what was once a vital instrument for building and maintaining social solidarity and for directing inevitable class tensions and social conflict toward democratic and egalitarian ends. Jack Metzgar, a Working-Class Perspectives stalwart, makes an important point about strikes in his stunning account of the mammoth 1959 steel strike, Striking Steel: Solidarity Remembered. Metzgar reminds us that the struggle was not ultimately about “pennies-per-hour” as much as it was about “defending the life and prospects” that workers had been struggling to build through the years.

What happens when workers no longer have the power to stage such a defense?

On January 6 we got a glimpse of what can grow in the vacuum created by the continued erosion of a robust tradition of workers’ collective action. The insurrectionists were not themselves primarily working-class, as Adam Serwer has noted. They skewed middle-class and included “business owners, CEOs, state legislators, police officers, active and retired service members, [and] real-estate brokers” among their number. Like PATCO’s strikers, they turned to collective action to challenge “the established order.” But both the form of solidarity they sought to invoke—deeply infused with white supremacism—and their goals could not have been more different. The insurrectionists weren’t seeking to shut down the air traffic system in order to win fairer treatment at work; they sought to overthrow the very processes of representative democracy.

The different uses of the “Don’t Tread On Me” flag in these two pivotal episodes separated by 40 years, makes clear that the diminution of working-class power over that span is the crucial yet often overlooked element that has most imperiled our fragile, multi-racial democracy. It suggests that we will not be able to successfully defend democracy from those who would undermine it unless we also find ways to empower workers once again to defend their interests effectively through collective action.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 16th, 2021

August 16th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: