If that’s not enough to unsettle the White House and its allies, consider this: Presidents have almost no power to ease the pain of inflation, and the voting public cuts presidents no slack at all because of that impotence. Look into the toolbox of our country’s chief executive and you’ll find it empty of effective tools, filled instead with devices now obsolete or laughable or meaningless or politically destructive.

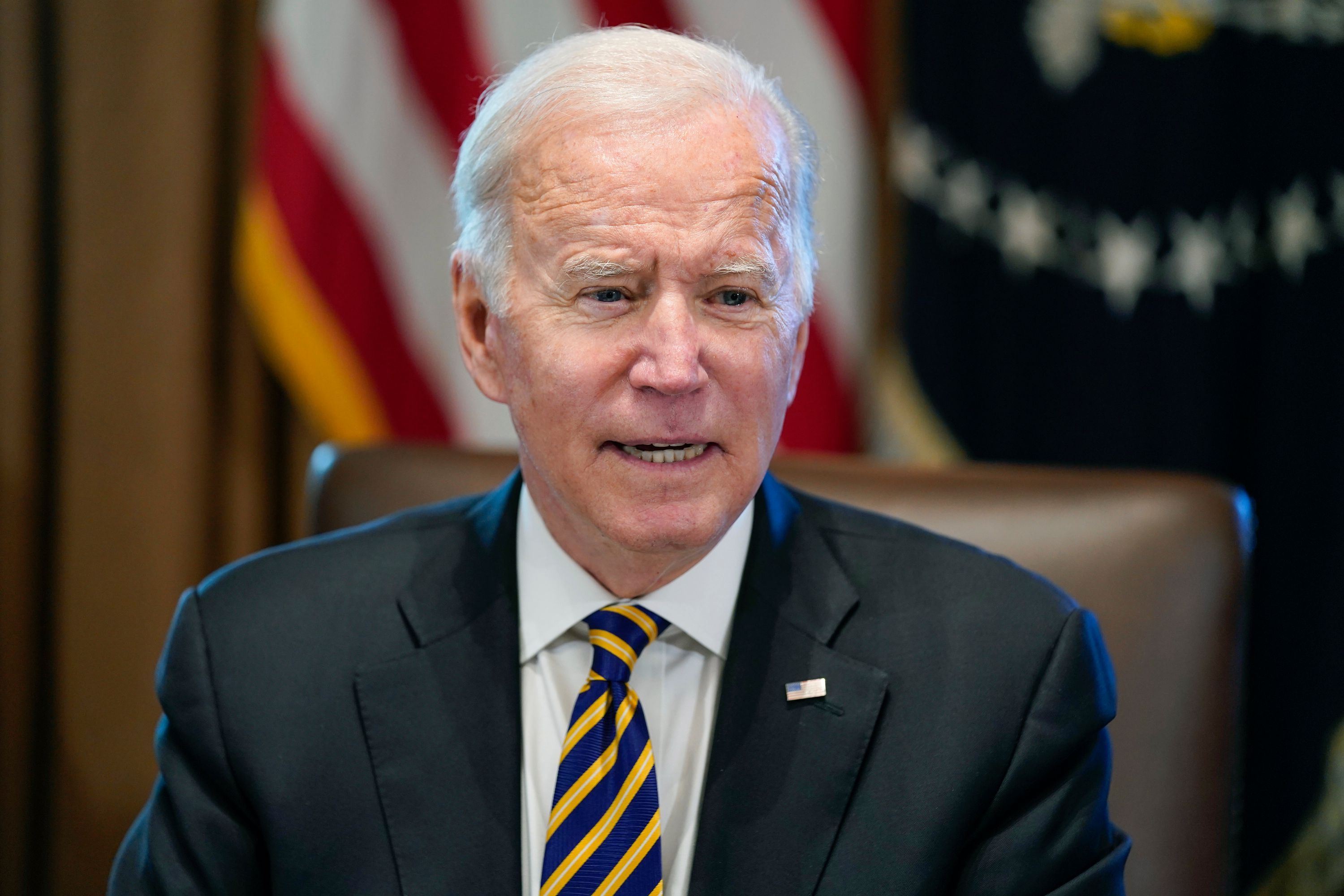

Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson were fans of “jawboning” — using their influence to persuade unions and companies to hold down wage and price increases. But those were days when large, powerful unions — the auto workers, steel workers, Teamsters — and large, powerful corporations like General Motors or US Steel could significantly affect the larger economy with their decisions. Who would Joe Biden “jawbone” now? The thousands of potential truck drivers whose absence from the road is helping to drive up costs? Asian factories where a microchip shortage has driven up the cost of new cars, which in turn has driven up the cost of used cars? The OPEC+ cartel, which has no interest in increasing oil production and may indeed be looking forward to $100 a barrel costs?

Richard Nixon tried a much more blunt instrument: In August of 1971, using powers that a Democratic Congress had delegated to him, he imposed a 90-day freeze on wages and prices. In the short run, it worked; but just as a temporary seal does not actually fix a leak, inflation resumed as soon as the controls ended. Inflation was running at over 11 percent by the summer of 1974, a drag on the economy that undermined Nixon’s standing even as the Watergate waters were rising. (As Bill Clinton would later demonstrate, a vibrant, full employment-low inflation economy is enormously helpful to a politically embattled president.)

When Nixon’s helicopter lifted off the White House lawn, Gerald Ford was left with the double-digit inflation. His response was, in effect, a pep rally.

On Oct. 8, 1974, the president addressed a Joint Session of Congress and reported: “There is only one point on which all advisers have agreed: We must whip inflation right now.”

What followed was a textbook case of presidential irrelevance. Noting the pain at the grocery store, Ford said: “To halt higher food prices, we must produce more food, and I call upon every farmer to produce to full capacity.” To check the rising cost of professional services, he said: “The administration will zero in on more effective enforcement of laws against price fixing and bid rigging. For instance, non-competitive professional fee schedules and real estate settlement fees must be eliminated. Such violations will be prosecuted by the Department of Justice to the full extent of the law.”

He also asked Americans to send him 10 energy-saving ideas, and finally, he displayed “the symbol of this new mobilization, which I am wearing on my lapel. It bears the single word WIN. I think that tells it all. I will call upon every American to join in this massive mobilization and stick with it until we do win as a nation and as a people.”

The red and white “WIN” button instead became a different kind of symbol. Alan Greenspan, then-Ford’s Council of Economic Advisors chair, later recalled thinking that the campaign was “unbelievably stupid.” New York Magazine, in a column ridiculing Ford, showed a clown with a “WIN” button.

But if you’re looking for a president who did in fact do something to tame inflation — albeit indirectly — it was Jimmy Carter. When he appointed Paul Volcker as chair of the Federal Reserve Board, he put someone in a position of real power who was determined to fully exercise that power, no matter the consequences.

With an inflation rate in 1980 of more than 13 percent — “It was the biggest inflation and the most sustained inflation that the United States had ever had,” Volcker recalled — he led the Fed to a historic tightening of the money supply. Interest rates rose vertiginously; at one point the prime rate hit 21 percent. The consequences were dramatic and ugly — a recession more severe than any since the Great Depression. Four million workers lost their jobs.

The “stagflation” — a toxic combination of inflation and unemployment — helped send Carter down to a landslide defeat in 1980. By 1982, the unemployment rate hit 10 percent, a number high enough to cost Republicans 27 seats in the House. By 1984, however, unemployment was moving in the right direction, dropping to just over 7 percent. Economic growth was over 7 percent, inflation had dropped to under 4 percent — and Ronald Reagan won a 49-state re-election.

The United Sates has not faced a genuinely worrisome inflation rate since, and that’s another source of pain for Biden and his party. Americans have had no experience in decades with prices rising across the board; a 6 or 7 percent inflation rate is nothing compared to the Carter era, but it looks particularly worrisome compared with the recent past.

So what can Biden offer? He can turn to the Strategic Petroleum Reserve — the refuge of presidents past — which holds what can fairly be described as a drop in the ocean of the nation’s energy needs. He and his team can argue that the just-passed infrastructure bill will increase productivity by making the transportation of goods more efficient. But that reality is years away, and the short-term impact — roads, bridges and rail lines closed for repair — would in fact create short-term inefficiency.

As for the “Build Back Better” bill — the inflation numbers may make it much harder to get that legislation through Congress. Larry Summers, perhaps the most prominent economist warning about inflation, supports the legislation. But Sen. Joe Manchin’s recent comments make it clear he’s in no rush to provide the 50th vote needed to pass it.

If Biden’s advisors are right, 2022 will see the lessening of inflation, as goods flow into the stores and automobile lots where cash-flushed customers will no longer bid up the costs of scarce items. But that’s more of a hope than a certainty; the White House description last summer of the “transitory” nature of this inflation seems a lot less convincing now, and the prospect of Christmas season with high priced or unavailable goods and sharply higher fuel costs does not bode well for the president’s already-sinking approval numbers.

There’s good reason not to put much stock in the Republican arguments that this inflation is all due to what Sen. Marco Rubio called “the left-wing lunatics” running the government, any more than Richard Nixon or Gerald Ford or Jimmy Carter were to blame for OPEC sending the price of oil through the roof decades ago. But that is cold comfort for Biden and the Democrats. Maybe somewhere in the past, there’s an incumbent White House party that performed well in an election where inflation was a dominant concern. But if you’re looking back over the last three-quarters of a century or so, you’re going to come up empty.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 16th, 2021

November 16th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: