A team of archaeologists and anthropologists from the University of Michigan found something highly unusual while exploring the underwater realms of Lake Huron in the Great Lakes region. Supervised by their team leader, anthropologist John O’Shea, they were digging on the Alpena-Amberley Ridge, a narrow land corridor occupied by Native Americans before it was permanently flooded 8,000 years ago. While sorting through a sample of rocks that showed signs of being altered by human hands, they found two shiny glass shards of obsidian that had apparently flaked off some sort of sharp-edged tool. Further analysis showed that this obsidian was from Oregon, pointing to little-understood ancient long-distance trade networks.

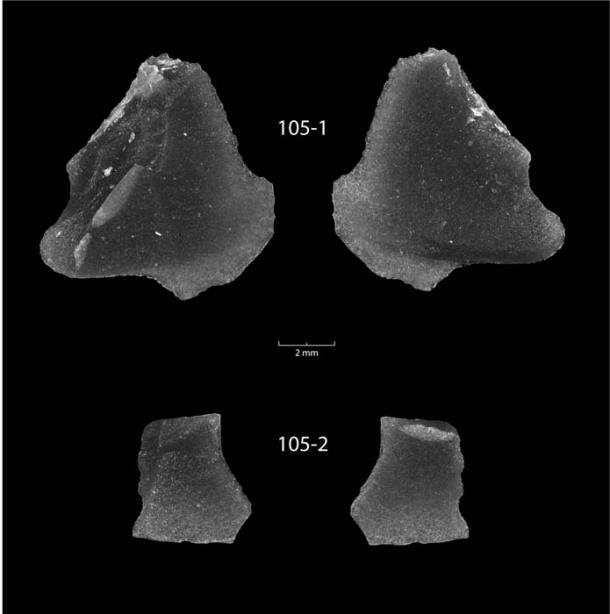

Photomicrographs of the two obsidian flakes found beneath Lake Huron on a dark field to highlight flake modification. ( PLOS ONE )

Finding Obsidian Underwater at Lake Huron Was Strange

Obsidian is a hard, glassy rock produced by volcanoes. It has been used throughout human history to create cutting, slicing, or penetrating tools. Nevertheless, the scientists were quite surprised to find obsidian at this underwater site.

Obsidian occurs naturally in the Pacific Northwest, but not in the eastern United States. Native Americans living in the east were only able to obtain it through long-distance trade. Radiocarbon dating confirmed that the obsidian found under Lake Huron was buried in a layer that had been deposited approximately 9,000 years ago, when North America was transitioning from the late Pleistocene (the end of the last Ice Age) to the early Holocene .

This would push the creation of long-distance trade networks back to a time before they were previously believed to exist.

Other obsidian artifacts have been found east of the Mississippi River, most commonly at sites linked to the Ohio River Valley Hopewell culture . But all were left behind much more recently (Hopewell sites date to about 100 BC or later).

A deeper analysis of the obsidian flakes produced another surprise. Obsidian samples have characteristic signatures that allow them to be traced to their point of origin. After testing was complete, it was revealed that the Lake Huron obsidian flakes had been mined from the well-known Wagontire site in Central Oregon , 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) away from the Lake Huron basin.

This is the first time an obsidian sample has been found in the eastern United States that could be traced to this location. Other later samples all came from much closer, mostly from sites in Wyoming and New Mexico.

The implications of this discovery are profound.

“While it is notoriously difficult to parse out the specific means for the long-distance movement of goods among mobile foraging populations, it seems probable that these specimens arrived in the Great Lakes through multiple hands, rather than through any direct access to the central Oregon obsidian source,” O’Shea and his co-authors wrote in a May 19 article discussing their discovery in the journal PLOS One . “The artifacts reported therefore likely reflect the existence of continent-wide social networks that extended west-to-east across the recently deglaciated landscapes of North America at the end of the Pleistocene.”

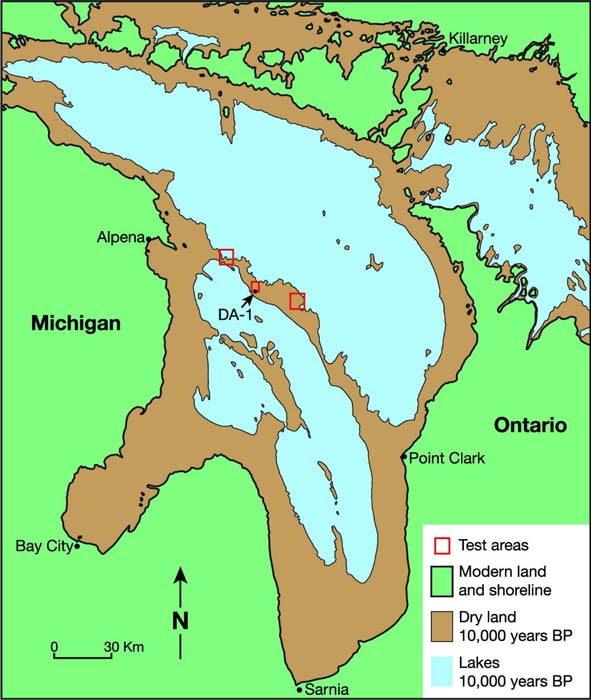

Map of the Lake Huron Basin. Areas shaded in green represent the modern coast and land surface; brown areas represent dry land during the Lake Stanley lowstand, and blue represents the location of the lakes at approximately 10,000 years ago. Red rectangles represent areas where archaeological research has been conducted. The location of the obsidian finds, sample DA-1, is indicated. ( PLOS ONE )

Who Were the Alpena-Amberley People?

When it was still above water, the Alpena-Amberley Ridge connected the landmasses of what are now Michigan and Ontario. It would have been hidden by glacial cover up until about 10,000 years ago and would have remained above the water level for about 2,000 years after that.

In the centuries before the bridge was finally submerged, it was inhabited by a Native American group (still unidentified) that built their own unique culture.

The inhabitants of the land bridge exploited its characteristics in their hunting practices . They created steadily narrowing tunnels from stone barriers, which funneled caribou herds in a single direction while allowing them no path of escape once they were pounced upon by hunting parties.

The Alpena-Amberley inhabitants further supplemented their diet through fishing, enjoying the bounty provided by adjacent Lake Stanley (the precursor to Lake Huron, which was created later, along with the rest of the Great Lakes by glacial melt).

The material culture of this group was also unique. The tools recovered from Alpena-Amberley digs are smaller than those found at other Great Lakes sites, and samples from obsidian tools have not been found anywhere else in the region.

Working under the authority of the University of Michigan’s Museum of Anthropological Archaeology , O’Shea and his team have been diving and excavating in Lake Huron for more than a decade. Since the land bridge they’ve concentrated on is now 100 feet below the water, this work has proven challenging. What they’ve uncovered so far has given them some idea of how the Native Americans who occupied the Alpena-Amberley corridor lived, but many questions remain.

One of the biggest is whether they were connected to a long-distance exchange network that regularly supplied them with obsidian. More excavations will be required before archaeologists are able to answer this very important question.

Diver and MSU alum Tyler Schultz and ‘Jake’ the ROV collect samples in central Lake Huron, where the obsidian flakes were found. (John O’Shea / University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology )

In Search of the Underwater Secrets of Antiquity

The obsidian flakes discovered on the floor of Lake Huron are tiny. But their impact is significant.

“These specimens provide greater resolution , as well as greater complexity, to an important and poorly understood time period in the North American past,” O’Shea and his colleagues commented in their PLOS One article.

As this exciting discovery reveals, underwater explorations have the potential to fill in knowledge gaps, in the Great Lakes region and beyond. The melting of the glaciers after the end of the last Ice Age undoubtedly submerged many important archaeological sites in North America and elsewhere.

Some of these sites may have many surprising secrets to reveal, secrets that could be significant enough to cause drastic alterations in accepted theories about prehistory.

Top image: Black obsidian from Armenia isolated on white background. Not all obsidian is black, but the flakes found beneath Lake Huron by archaeological divers were black. Source: Björn Wylezich / Adobe Stock

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 3rd, 2021

June 3rd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: