Police Commissioner Karen Webb says she has “zero tolerance” for domestic violence but that attempts to sack officers who break the law are not always successful.(AAP: Bianca De Marchi)

Documents obtained by ABC News under Freedom of Information reveal 27 NSW police officers were charged with domestic violence in 2019 and 2020. Of those, five male officers were convicted of their charges in court, three of whom are still serving — including a senior constable convicted of two counts of assault occasioning actual bodily harm, two counts of common assault and breaching his AVO. Three other officers who were found guilty of their assault charges without conviction are also still serving.

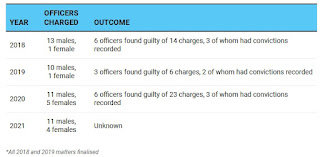

A further 15 NSW police officers — 11 men and four women — were last year charged with domestic violence offences including destroying property, assault, stalking/intimidation, choking and using a carriage service to make threats to kill, documents show. The 2021 data is similar to that obtained in previous years, with 16 officers charged with domestic violence in 2020 and 11 in 2019.

Police Commissioner Karen Webb, who was formally sworn in to her role in February, said she had “zero tolerance” for domestic violence but that attempts to sack officers who break the law were subject to appeal, and not always successful.

“Obviously I haven’t had to adjudicate on any of these matters — I’ve been Commissioner for the last 60-odd days,” Commissioner Webb told ABC News. “I’ve got a very strong position on domestic violence generally … [but] I can’t speak for [decisions made by] my predecessors.”

NSW Police officers charged with domestic violence

The NSW Police Force employs 17,727 police officers.

When asked whether the public could trust the NSW Police Force to respond well to domestic violence in the community if officers found guilty of such abuse were permitted to continue serving, Commissioner Webb said it was a “reasonable question”.

She said she was “sure” the six officers still serving after being found guilty or convicted of domestic violence would have faced disciplinary action and didn’t think they’d still be on the frontline, but her office did not provide details by the ABC’s deadline.

Still, it’s relatively uncommon for police officers in Australia to be charged with domestic violence, let alone be found guilty in court. For context, in the year ending June 2021, 89 per cent of domestic violence defendants in NSW had a guilty outcome. Of the 27 officers charged with domestic violence in 2019 and 2020, however, just a third were found guilty with or without conviction, in line with trends in other states.

Figures undermine confidence in police, advocates say

Advocates say the figures are further evidence the NSW Police Force, like other Australian law enforcement agencies, has been failing to hold abusive officers to account, and contradict claims by senior police that the organisation has “zero tolerance” for criminal behaviour. As an ABC News investigation first revealed in 2020, police forces are too often failing to take action against domestic violence perpetrators in their ranks, deterring victims from reporting abuse and fuelling cultures of impunity.

It comes following a scathing assessment of how NSW police are responding to domestic violence across the board, with the auditor-general’s performance audit last week finding numerous flaws and failures in the force’s domestic violence operations, including with its handling of investigations into serving officers.

“It’s difficult to believe that police officers found guilty of criminal offences are still allowed to serve in the police force,” potentially responding to domestic violence incidents in the community, said Kerrie Thompson, chief executive of the Victims of Crime Assistance League (VOCAL).

“It undermines the good work that the majority of police are doing in responding to domestic violence. The community expects police officers to display a high standard of integrity and uphold the law,” Ms Thompson said. “These findings raise questions about how and why officers are allowed to keep their job when they are convicted of criminal offences.”

Senior constables in particular are “at the forefront” of domestic violence policing, she added — they frequently respond to domestic violence calls and take victim-survivor reports: “If they are perpetrators of the same abuse, I’m deeply concerned about their ability to provide adequate support to victim-survivors of family and domestic violence.”

Sacking police officers in NSW

The NSW Police Commissioner can remove a police officer from the force under section 181D of the Police Act if they lose confidence in their suitability to continue as an officer. Officers who engage in misconduct may also face internal disciplinary action including a reduction in rank or pay or transferral to other duties.

Those found guilty of criminal behaviour are automatically referred for consideration for a Commissioner’s loss of confidence, Commissioner Webb said, with each case assessed on its own merits: “But … I don’t have blanket approval for automatic removal and I have to take everything into consideration in making my decisions.”

In other words, committing domestic violence is not necessarily considered serious enough misconduct to warrant sacking a police officer.

That’s not to say it hasn’t featured in matters before the Industrial Relations Commission. In one case heard in 2020, a former police officer appealed the Police Commissioner’s decision to sack him for 11 findings of misconduct — including that he threatened and assaulted his partner — claiming his removal would be harsh. The Commissioner (then Mick Fuller) disagreed, arguing the NSW Police Force “has no tolerance for domestic violence behaviour”, which he described as “criminal conduct and inimical to our sworn oath of office”.

When one of the “key missions” of the force is to “drive out the scourge of domestic violence”, the Police Commissioner said, “I can no longer have confidence in you to contribute toward the achievement of such a goal, in view of your misconduct”. The industrial relations commissioner John Murphy concluded the officer’s removal was neither harsh, unreasonable or unjust and dismissed his application for review.

Still, advocates and lawyers have pointed to inconsistencies between how senior police claim they respond to abusers in their ranks and the disturbing experiences many victims say they’ve had after seeking help from local officers.

A ‘stark window’ into victims’ experiences

Lauren Caulfield, coordinator of the Policing Family Violence Project, said the new figures obtained by ABC News were “distressing, angering and chilling” and added to mounting evidence in Australia and internationally that police officers who perpetrate domestic violence are significantly less likely to be charged and convicted than abusers in the general community.

“The types of charges reflected in the data represent serious, high-risk and sometimes life-threatening violence … it’s a stark window into the experiences of victim-survivors who have reported this to police,” Ms Caulfield said — and many don’t. “Victim-survivors often speak of the way that police abusers weaponise their authority and knowledge of the family violence and legal systems — the ways their police badge shields them from accountability.”

That at least six officers recently found guilty and or convicted of their charges are still employed by the NSW Police Force should be of “serious concern” to the public, Ms Caulfield added. As a point of reference, she said, a domestic violence conviction often precludes members of the general community from volunteering at many organisations.

“It is beyond concerning that officers using domestic violence — and even those found guilty of this in court — are still serving,” Ms Caulfield said. “These figures contradict and undermine claims by senior police that officers who perpetrate domestic violence are held to the same standard as members of the wider community and instead reveal a pattern of impunity for officers who abuse.”

Experts say one of the most pressing problems is that the NSW Police Force doesn’t have a specific policy for dealing with employees who perpetrate domestic violence, and that investigations into serving officers are frequently managed by police from the same station or command, potentially creating conflicts of interest and implications for victims’ safety and privacy.

The auditor-general’s performance audit released last week identified more or less the same issue. It found that while the force has basic procedures for responding to allegations against serving officers — such as securing the alleged perpetrator’s service weapons — there is no guidance for managing conflicts of interest and ensuring investigations are independent. It recommended the force review its process for investigating domestic violence matters involving employees and implement procedures to safeguard their independence and mitigate conflicts of interest.

Yet police accountability lawyers have argued police shouldn’t be investigating themselves, and that the police complaints and oversight system is not sufficiently independent. For instance, complaints about police conduct in NSW can be made to the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission. But the LECC is notoriously under-resourced and refers some 98 per cent of what it has called a “firehose” of complaints back to police for investigation.

‘I’ll be looking to improve where I can’

Commissioner Webb said she “welcomed” the auditor-general’s findings and would work with the Audit Office and stakeholders to address its eight recommendations, but insisted NSW police managed conflicts of interest well and “put victims’ needs first”.

“An investigator that’s allocated to a matter like this would have significant experience and have to declare up front … that there is no conflict that can’t be managed,” Commissioner Webb said. “And if there is one, then it’s given to another neighbouring command or our Professional Standards Command, which is made up of teams of detectives.”

Other police forces have attempted to address glaring problems with how they respond to employees who perpetrate domestic violence and stop abusive police being given “special treatment”. Victoria Police, for instance, recently launched a standalone policy for dealing with such matters and stood up a unit in its Professional Standards Command to investigate high-risk cases.

But Commissioner Webb, whose force responds to 140,000 calls for help with domestic violence per year, said she would prioritise servicing the broader community before considering whether she needs a specialist unit for dealing with perpetrators in police.

“Having said that, my internal affairs unit is made up of detectives, designated criminal investigators that specialise and have all the skills to investigate any type of criminal offence, not just DV,” she said. “And certainly while I’m in the role here, I’ll be looking to improve where I can, and if that means I’ve got to change some things around delegations and authorities, then I will.”

Source:abc.net.au

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 11th, 2022

May 11th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: