Germany eventually signed the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, because she faced death by starvation and invasion if she refused. With the naval blockade still in force and her merchant ships and even Baltic fishing boats sequestered, Germany could not feed her people. Germany’s request to buy 2.5 million tons of food was denied by the Allies. U.S. warships now supported the blockade. With German families starving, Bolshevik uprisings in several German cities, Trotsky’s Red Army driving into Europe, Czechs and Poles ready to strike from the east, and Allied forces prepared to march on Berlin, Germany was forced to capitulate.[11]

By John Wear

The Treaty of Versailles is sometimes said to be the beginning of the Second World War. The Versailles Treaty crushed Germany beneath a burden of shame and reparations, stole vital German territories, and rendered Germany defenseless against enemies from within and without. Britain’s David Lloyd George warned the treaty makers at Versailles:

If peace is made under these conditions, it will be the source of a new war.”[1]

We will examine in this section some of the provisions of the Versailles Treaty that made it so unfair to Germany.

President Woodrow Wilson in an address to Congress on January 8, 1918, set forth his Fourteen Points as a blueprint to peacefully end World War I. The main principles of Wilson’s Fourteen Points were a nonvindictive peace, national self-determination, government by the consent of the governed, an end of secret treaties, and an association of nations strong enough to check aggression and keep the peace in the future. Faced with ever increasing American reinforcements of troops and supplies and a starvation blockade imposed by the Allies, Germany decided to end World War I by signing an armistice on November 11, 1918. The parties agreed to a pre-Armistice contract that bound the Allies to make the final peace treaty conform to Wilson’s Fourteen Points.[2]

The Treaty of Versailles was a deliberate violation of the pre-Armistice contract. Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles placed upon Germany the sole responsibility:

for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.”

This so-called “war guilt clause” was fundamentally unfair and aroused widespread hatred among virtually all Germans. It linked up Germany’s obligation to pay reparations with a blanket self-condemnation to which almost no German could subscribe.[3]

The Allies under the Versailles Treaty could set reparations at any amount they wanted. In 1920, the Allies set the final bill for reparations at the impossible sum of 269 billion gold marks.[4] The Allied Reparations Committee in 1921 lowered the amount of reparations to 132 billion gold marks or approximately 33 billion dollars–still an unrealistic demand.[5]

The Allied representatives at the Paris Peace Conference decided that Germany should lose all of her colonies. All private property of German citizens in German colonies was also forfeited. The rationale for this decision was the hypocritical guise of humanitarian motives that claimed that Germany had totally failed to appreciate the duties of colonial trusteeship. Germany was extremely upset that the Allied governments refused to count the loss of her colonies as a credit in her reparations account. Some Germans estimated the value of Germany’s colonies at nine billion dollars. This was a large sum of money that would have greatly reduced Germany’s financial burden to pay reparations under the treaty’s war guilt clause.[6]

GERMANS PROTESTING THEIR EXPULSION FROM THEIR HOME COUNTRIES. PROTESTING THE “PEACE” TREATY. 1, 2.

The Treaty of Versailles forced Germany to cede 73,485 square kilometers of her territory, inhabited by 7,325,000 people, to neighboring states. Germany lost 75% of her annual production of zinc ore, 74.8% of iron ore, 7.7% of lead ore, 28.7% of coal, and 4% of potash. Of her annual agricultural production, Germany lost 19.7% in potatoes, 18.2% in rye, 17.2% in barley, 12.6% in wheat, and 9.6% in oats. The Saar territory and other regions to the west of the Rhine were occupied by foreign troops and were to remain occupied for 15 years until a plebiscite was held. The costs of the occupation of the Saar territory totaling 3.64 billion gold marks had to be paid by Germany.[7]

The Versailles Treaty forced Germany to disarm almost completely. The treaty abolished the general draft, prohibited all artillery and tanks, allowed a volunteer army of only 100,000 troops and officers, and abolished the air force. The navy was reduced to six capital ships, six light cruisers, 12 destroyers, 12 torpedo-boats, 15,000 men and 500 officers. After the delivery of its remaining navy, Germany had to hand over its merchant ships to the Allies with only a few exceptions. All German rivers had to be internationalized and overseas cables ceded to the victors. An international military committee oversaw the process of disarmament until 1927.[8]

The German delegation in Paris was formally presented with the terms of the Treaty of Versailles on May 7, 1919. At first the German delegation refused to sign the treaty. After German delegate Johann Giesberts read the long list of humiliating provisions of the treaty, he stated with vehemence:

This shameful treaty has broken me, for I believed in Wilson until today. I believed him to be an honest man, and now that scoundrel brings us such a treaty.”[9]

German foreign minister Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau replied:

…It is demanded of us that we admit ourselves to be the only ones guilty of the war. Such a confession in my mouth would be a lie. We are far from declining any responsibility for this great world war… but we energetically deny that Germany and its people, who were convinced that they were making a war of defense, were alone guilty….”[10]

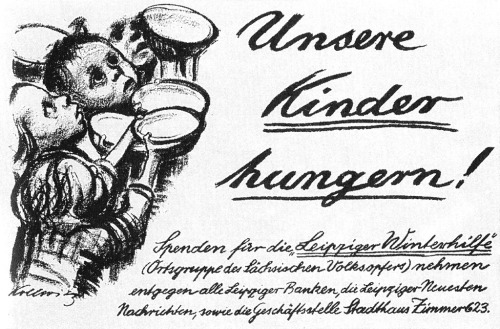

Germany eventually signed the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, because she faced death by starvation and invasion if she refused. With the naval blockade still in force and her merchant ships and even Baltic fishing boats sequestered, Germany could not feed her people. Germany’s request to buy 2.5 million tons of food was denied by the Allies. U.S. warships now supported the blockade. With German families starving, Bolshevik uprisings in several German cities, Trotsky’s Red Army driving into Europe, Czechs and Poles ready to strike from the east, and Allied forces prepared to march on Berlin, Germany was forced to capitulate.[11]

Francesco Nitti, Prime Minister of Italy, said of the Versailles Treaty:

It will remain forever a terrible precedent in modern history that against all pledges, all precedents and all traditions, the representatives of Germany were never even heard; nothing was left to them but to sign a treaty at a moment when famine and exhaustion and threat of revolution made it impossible not to sign it.…”[12]

It is estimated that approximately 800,000 Germans perished because of the Allied naval blockade.[13] The blockade’s architect and chief advocate had been the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. His confessed aim had been to starve the whole German population into submission.[14] One commentator noted the effects of the blockade:

Nations can take philosophically the hardships of war. But when they lay down their arms and surrender on assurances that they may have food for their women and children, and then find that this worst instrument of attack on them is maintained—then hate never dies.”[15]

Herbert Hoover said of the Allied blockade in Germany:

The blockade should be taken off…these people should be allowed to return to production not only to save themselves from starvation and misery but that there should be awakened in them some resolution for continued National life…the people are simply in a state of moral collapse…We have for the last month held that it is now too late to save the situation.”[16]

When Hoover was in Brussels in 1919, a British admiral arrogantly said to him,

Young man, I don’t see why you Americans want to feed these Germans.”

Hoover impudently replied,

Old man, I don’t understand why you British want to starve women and children after they are licked.”[17]

George E. R. Gedye was sent to Germany in February 1919 on an inspection tour. Gedye described the impact of the blockade upon the German people:

…Hospital conditions were appalling. A steady average of 10 percent of the patients had died during the war years from lack of fats, milk and good flour. Camphor, glycerine and cod-liver oil were unprocurable. This resulted in high infant mortality…We saw some terrible sights in the children’s hospital, such as the “starvation babies” with ugly, swollen heads…Such were the conditions in Unoccupied Territory. Our report naturally urged the immediate opening of the frontiers for fats, milk and flour…but the terrible blockade was maintained as a result of French insistence…until the Treaty of Versailles was signed in June, 1919…No severity of punishment could restrain the Anglo-American divisions of the Rhine from sharing their rations with their starving German fellow-creatures.[18]

Few historians in postwar years believed Germany to be solely responsible for the outbreak of World War I. There were differences of opinion about the degree of responsibility borne by Germany, Great Britain, France, Russia, and other belligerent nations, but no responsible person could find Germany totally responsible for the war. Representative of impartial scholarship on the subject is the opinion of Dr. Sidney B. Fay of Harvard University. Fay concluded after an extensive study of the causes of World War I:

Germany did not plot a European war, did not want one and made genuine, though too belated efforts to avert one…It was primarily Russia’s general mobilization, made when Germany was trying to bring Austria to a settlement, which precipitated the final catastrophe, causing Germany to mobilize and bring war…The verdict of the Versailles Treaty that Germany and her allies were responsible for the war, in view of the evidence now available, is historically unsound.[19]

Other historians who established that Germany was not primarily responsible for causing World War I include Professors Harry Elmer Barnes, Michael H. Cochran, Max Montgelas, and Georges Demartial. The Englishman Arthur Ponsonby also convincingly demonstrated that atrocity charges against the Germans were manufactured by Allied propagandists.[20]

Most American liberals who had originally supported American involvement in World War I eventually repudiated the thesis of unique German responsibility for the war. They logically denounced the failure to revise the Treaty of Versailles with its absurd attempt to collect astronomical reparations from Germany.[21]

Despite the unfairness of the Treaty of Versailles, its provisions remained in effect and were formally confirmed by the Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact of 1928. Germans regarded the provisions of the Versailles Treaty as chains of slavery that needed to be broken. One German commented in regard to the Versailles Treaty,

The will to break the chains of slavery will be implanted from childhood on.”[22]

Adolf Hitler referred to the Versailles Treaty in Mein Kampf as

…a scandal and a disgrace…the dictate signified an act of highway robbery against our people.”[23]

Hitler was committed to breaking the chains of Versailles when he came to power in Germany in 1933.

Read More Here

ENDNOTES

[1] Degrelle, Leon, Hitler: Born at Versailles, Torrance, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1992, Author’s Preface, p. x.

[2] Chamberlain, William Henry, America’s Second Crusade, Chicago: Regnery, 1950, pp. 13-15, 20-22.

[3] Tansill, Charles C., “The United States and the Road to War in Europe,” in Barnes, Harry Elmer (ed.), Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, Newport Beach, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, pp. 81, 84.

[4] Franz-Willing, “The Origins of the Second World War,” The Journal of Historical Review, Torrance, CA: Vol. 7, No. 1, Spring 1986, p. 103.

[5] Ibid., see also Tansill, Charles C., “The United States and the Road to War in Europe,” in Barnes, Harry Elmer (ed.), Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, Newport Beach, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, p. 85.

[6] Tansill, Charles C., “The United States and the Road to War in Europe,” in Barnes, Harry Elmer (ed.), Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, Newport Beach, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, pp. 86-87.

[7] Franz-Willing, “The Origins of the Second World War,” The Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 7, No. 1, Spring 1986, p. 103.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Luckau, Alma, The German Delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, New York: Columbia University Press, 1941, p. 124.

[10] Denman, Roy, Missed Chances: Britain and Europe in the Twentieth Century, London: Indigo, 1997, p. 48; see also Mee, Charles L., The End of Order: Versailles 1919, New York: E. P. Dutton, 1980, pp. 215-216.

[11] Buchanan, Patrick J., Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War, New York: Crown Publishers, 2008, pp. 77, 83.

[12] Hoover, Herbert, Memoirs, Vol. 1, Years of Adventure, New York: MacMillan, 1951-1952, p. 341.

[13] Tansill, Charles C., “The United States and the Road to War in Europe,” in Barnes, Harry Elmer (ed.), Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, Newport Beach, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, p. 96.

[14] Buchanan, Patrick J., Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War, New York: Crown Publishers, 2008, p. 79.

[15] Tansill, Charles C., Back Door to War: The Roosevelt Foreign Policy 1933-1941, Chicago: Regnery, 1952, p. 24.

[16] O’Brien, Francis William (ed.), Two Peacemakers in Paris: The Hoover-Wilson Post-Armistice Letters, 1918-1920, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1978, p. 129.

[17] Hoover, Herbert, Memoirs, Vol. 1, Years of Adventure, New York: MacMillan, 1951-1952, p. 345.

[18] Gedye, George E. R., The Revolver Republic; France’s Bid for the Rhine, London: J. W. Arrowsmith, Ltd., 1930, pp. 29-31.

[19] Fay, Sidney B., The Origins of the World War, New York: Macmillan, 1930, pp. 552, 554-555.

[20] Ponsonby, Arthur, Falsehood in Wartime, Costa Mesa, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1991.

[21] Barnes, Harry Elmer, Barnes Against the Blackout, Costa Mesa, CA: The Institute for Historical Review, 1991, p. 159.

[22] Luckau, Alma, The German Delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, New York: Columbia University Press, 1941, pp. 98-100.

[23] Hitler, Adolf, Mein Kampf, translated by James Murphy, London: Hurst and Blackett Ltd., 1942, p. 260.

Source Article from http://www.renegadetribune.com/no-mercy-unprecedented-vengeance-versailles-treaty/

Related posts:

Views: 26

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 12th, 2017

November 12th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: