Expert researchers with an interest in ancient European rock art have just completed an exhaustive study of Romanelli Cave, an impressively decorated rock art site located on the southeastern tip of Italy overlooking the Adriatic Sea. Despite Upper Paleolithic rock art first being found there in 1905, a complete survey of the cave’s rock art collection had never before been attempted.

Entrance of the Romanelli Cave. (D. Sigari / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

Discovering Unknown Rock Art at Romanelli Cave

During their study of Romanelli Cave the researchers found more than 30 new rock art panels, none of which had been discovered or looked at before. Their analysis of this engraved imagery has convinced them that the Romanelli Cave artists were working within the context of a unified cultural and artistic tradition. The elements of this tradition were passed between population groups in western and southern Europe and parts beyond between 14,000 and 11,000 years ago, at the very end of the Late Stone Age or Upper Paleolithic period.

The Italian archaeologists and earth scientists who participated in this study took pictures of the rock art panels they were most interested in analyzing. They wanted to avoid physical contact with them, since many of the Romanelli engravings were already damaged and they didn’t want to make the situation worse.

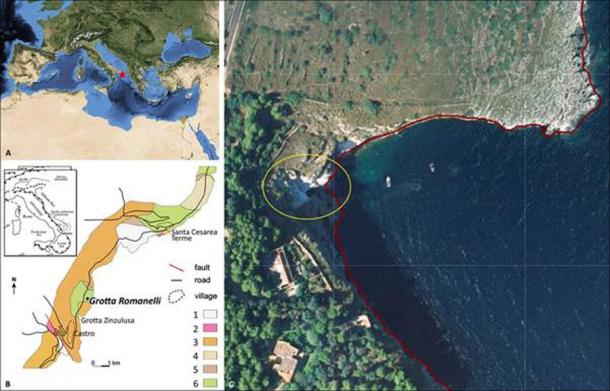

Location of Romanelli Cave in Italy. (Sigari et. al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

Deciphering the Romanelli Cave Art

As they poured over the photographs, they saw dozens of images of animals, including many engravings of bovines and a striking image of a large bird. They also found many images that were geometrical and abstract in nature, similar to those that have been prominently featured in rock art galleries at Upper Paleolithic period sites on virtually every continent.

The researchers also learned more about the engraving techniques and technologies used by the artists who made the images. They found obvious differences, which demonstrated that the artists didn’t all work at the same time or belong to the same cultures. Radiocarbon dating of various cave layers seemed to confirm this idea, as these results showed the cave had been occupied and used as a “canvas” by rock artists for as long as 5,000 years.

Their analysis was comprehensive, and their results could be a game-changer. The researchers believe they’ve found evidence of continuity or commonality between Upper Paleolithic rock artists working in different parts of Europe during the same general time period. “The new figures provide evidence of a shared visual heritage across a wide part of Eurasia during the Late Upper Paleolithic, opening new questions about social dynamics and the spread of common iconographic motifs around the Mediterranean Basin,” the Italian researchers wrote in an article introducing their findings in the journal Antiquity.

The auk head discovered at the Romanelli Cave in Italy. (Sigari et. al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

The Romanelli Cave Survey Results Explained

Archaeologists have traditionally categorized Upper Paleolithic cave art found in southern Italy and Sicily as separate from cave art from the same era found in France and on the Iberian Peninsula. The former has been classified as Mediterranean style, while the latter has been put in a category known as the Franco-Cantabrian style. Romanelli Cave has long been considered one of the most significant Mediterranean-style caves, grouped in with the Iberian Peninsula caves of La Pileta and Parpallò, Ebbou Cave in France, and Levanzo and the Addaura caves in Sicily.

In recent years, however, new discoveries and fresh analyses has called this division into question. Similarities and continuities between the two supposedly unique styles have been noticed, and archaeologists are now reevaluating the traditional categories. Motivated by these reevaluations, archaeologists and other ancient history aficionados became more interested in Romanelli Cave, and more curious about what might be found there.

In 2016, the researchers involved in the newest study officially launched their multidisciplinary research project. They wanted to learn more about the stylistic aspects of the Romanelli rock art , its subject matter, and the engraving tools and techniques used to create it. They also planned to perform new radiocarbon dating tests on various cave levels, to see if they could refine the timeline for the cave’s occupation more precisely.

As their survey progressed, they eventually focused on two specific areas of the cave that featured abundant collections of engraved rock art . Each area included some engravings that had been found before, and some that hadn’t. Photographs taken in the cave from years earlier showed that the newly discovered engravings had once been covered by cave sediments, which had finally been removed to reveal the hidden images.

Removing Cave Sediments to Reveal Familiar Rock Art

When they had the chance to examine all of the rock art in the two sections, the researchers felt they were looking at highly familiar imagery. It reminded them of cave art they’d seen before, in locations far distant from Italy’s southeastern peninsula. Engraved images of bovines were especially common at Romanelli Cave. It was normal for Upper Paleolithic rock artists to include engravings of animals which people depended on for food, and bovine-like creatures have been frequently found in rock art collections from caves all over Europe and elsewhere.

Another of the engravings at Romanelli Cave featured a large bird that resembled the great auk, a now-extinct flightless creature that survived until the 19th century in the North Atlantic region. Rock art images of auk-like figures have been found in a few other places, including in Western European caves where the Franco-Cantabrian style of rock art predominated. But this is still an unusual find, since drawings of birds are not as common in cave art as images of other animals.

There were also many abstract and geometrical figures in Romanelli Cave. These figures are ubiquitous, having been found on Upper Paleolithic rock art panels in Africa, Asia, Australia, and South America, in addition to being commonly displayed in rock art assemblages in caves in France and Spain. It has long been speculated that geometric figures and other abstract images in cave art are re-creations of imagery seen by shamans experiencing altered states of consciousness. Regardless of their ultimate meaning, this type of rock art has repeatedly been found at Upper Paleolithic rock art sites around the world.

Over the years, more than 100 examples of portable rock art have also been found in Romanelli cave. These engravings on smaller, more easily transportable rocks essentially match the images on the cave’s fixed surfaces, in content and style.

In addition to surveying the imagery, the scientists were also interested in studying the engraving techniques used to create the rock art at Romanelli Cave. They were eventually able to identify four distinct engraving styles, all of which would have made use of different types of engraving tools. This suggests the images on rock walls and ceilings were created over a period of centuries or perhaps even longer, by artists from different Upper Paleolithic cultures.

Finally, they also performed a number of new radiocarbon dating tests, on organic samples taken from various layers of the caves. The youngest layer tested was dated to between 9135 and 8639 years ago, while the oldest was dated to between 13,976 and 13,545 years ago. This update on past results expanded the cave’s occupational timeline, showing that art makers were active there for a longer period than previously believed.

Map showing distribution of auk figures. (Sigari et. al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

A Shared Rock Art Legacy?

Taken as a whole, the evidence the scientists collected undermines the idea that Mediterranean and Franco-Cantabrian styles were fully separate entities. Both might have existed, but likely had their roots in a common artistic tradition, the scientists have concluded. “The stylistic and thematic comparisons, together with the new radiocarbon-dating sequence, seem to confirm a possible connection with the iconographic tradition that developed out of the Italian peninsula after the Late Glacial Maximum, both in Iberia and France and the Late Upper Paleolithic of North Africa and the Caucasus,” they wrote in Antiquity.

“The discovery of the new engravings not only expands the figurative record of the Romanelli Cave and of Italian Paleolithic art more generally, but also marks an important step towards setting this site within the wider, more complex landscape of Paleolithic art,” highlighted the study.

The dynamics of how this unified tradition would have been passed from region to region in Upper Paleolithic Eurasia remains unknown. But if the scientists are correct in conclusions drawn from the Romanelli Cave, it means archaeologists and other prehistoric researchers who study cave art will have to put some of their old assumptions aside and look at rock art displays with fresh and unbiased eyes.

Top image: View of the Romanelli Cave in Italy. Source: Sigari et. al. / Antiquity Publications Ltd

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 13th, 2021

October 13th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: