An anthropologist from Iowa State University has found evidence in Mexico that humans lived in the Americas as far back as 33,000 years ago. This is 20,000 years earlier than the accepted date of arrival for the “First Americans,” who supposedly crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Asia before migrating southward around 11,000 BC.

The new Iowa State University discovery doesn’t negate the evidence that supports a more recent arrival. But it does contradict the theory that those later settlers were the first to occupy the lands of North and South America.

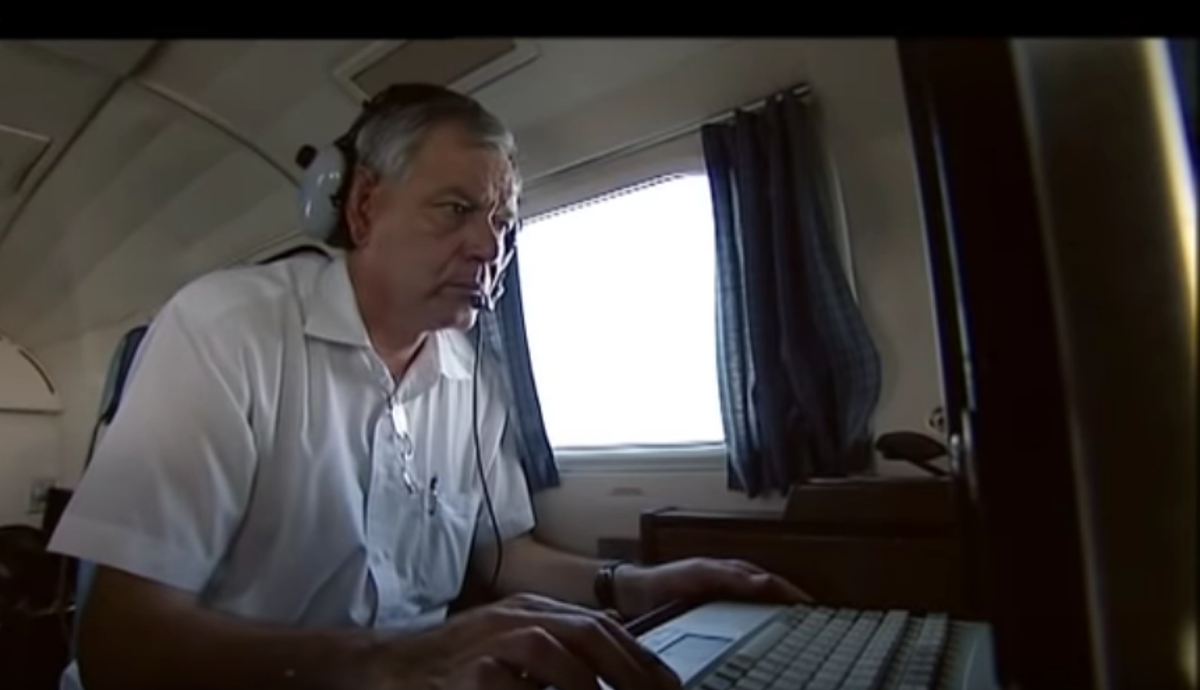

Iowa State anthropologist Andrew Somerville organized an expedition to Mexico to study the origins of agriculture in the Tehuacán Valley. Previous studies have shown that this region played a foundational role in the development of agriculture in the Americas, with samples of the earliest forms of several domesticated plant species having been found there during archaeological explorations.

Professor Andrew Somerville of Iowa State University led the recent study of the remains found in a Mexican cave that challenges the current theory of the first humans in the Americas. (Christopher Gannon / Iowa State University )

Mexico Cave Evidence and the First Humans in the Americas

Seeking to learn more about the history of human activity in the valley, Somerville and his associates tracked down bone samples that had been recovered from Coxcatlán Cave in the 1960s. Archaeological digs inside this cave, which was occupied by Native American peoples more than 10,000 years ago, had proven especially fruitful for scientists looking for data about social, cultural, and economic practices in the ancient Americas.

The bone samples Somerville and his cohorts obtained came from rabbits and deer, which presumably had been killed and eaten by the ancient inhabitants of the cave. These bones had been found at the bottommost layer of an excavation, meaning they had been deposited when the cave was first occupied. Through radiocarbon dating , the scientists hoped to discover exactly when humans began living in Coxcatlán Cave.

When submitting these materials for analysis, Somerville and his fellow scientists had no reason to suspect the tests would reveal anything surprising. But their assumptions were mistaken. According to the radiocarbon data, the deer and rabbit bones had been deposited in the cave between 33,448 and 28,279 years ago .

“We weren’t trying to weigh in on this debate or even find really old samples. We were just trying to situate our agricultural study with a firmer timeline,” Somerville said. “We were surprised to find these really old dates at the bottom of the cave, and it means that we need to take a closer look at the artifacts recovered from those levels.”

Previous radiocarbon testing had used plant and charcoal remains taken from the cave to establish timelines. Somerville points out that bones will produce more accurate radiocarbon results, meaning these latest tests should be recognized as definitive.

One of the rabbit bones, found in the Mexican cave, that was carbon dated for the study. This study essentially challenges existing theories on the arrival of the “First Americans,” pointing to arrival by sea long before the crossing of the Bering Strait land bridge. (Andrew Somerville / Iowa State University )

First Americans’ Research Must Continue, as Doubts Remain

While the radiocarbon dating data is impressive, it is not enough to clinch the case that humans were in Mexico 20,000 years earlier than believed.

An alternative hypothesis is that the rabbit and deer bones recovered from the cave could have come from animals that lived inside and died of natural causes. If the accepted theory is right and human beings were not living in the Americas in 30,000 BC, animals would have been the sole inhabitants of Coxcatlán Cave at that time.

This alternative seems plausible, but it does not align with previous research.

The deer and rabbit bones were recovered in the 1960s by scientists conducting a large-scale archaeological survey known as the Tehuacán Project , under the leadership or American archaeologist Richard S. MacNeish. Based on all of the evidence, MacNeish and his colleagues concluded that the bones were left behind in Coxcatlan Cave Zones XXVI and XXV by people.

“Zones XXVII, XXVI, and XXV contained a few artifacts, and a succession of small floors made up either of combined humic material and finely comminuted charcoal or vegetable matter clearly indicate human occupation,” MacNeish wrote in a 1972 textbook published by the University of Texas Press.

In an attempt to settle the question, Somerville and his team plan to examine the deer and rabbit bones more closely. They will be looking for tiny cutting marks , of the type that would have been caused if the flesh and hides of the animals had been removed by humans. They will also test the bones to see if they’ve been boiled or roasted over a fire, as they would have been if they were prepared as food.

The scientists will also look more closely at some of the artifacts that were found in the cave, specifically samples of what are purported to be stone tools . They will attempt to verify that these objects were created by humans and are not some type of artifact of nature.

Footprints leading across a snowy Arctic Ocean landscape but did the “First Americans” really arrive in North America by trekking across the Bering Strait. Or did they arrive by sea? Current evidence suggests both but that the sea crossings preceded the land crossing by up to 20,000 years. ( Kar-Man / Adobe Stock)

The First Americans Arrived By Land or By Sea or Both?

The conventional theory states that humans first arrived in the Americas by crossing a land bridge that once connected modern-day Siberia and Alaska. This land bridge was known as Beringia, and it was last open in the years between approximately 15,000 and 9,000 BC. Before this time, glaciers from the last Ice Age would have covered huge sections of the Americas, and after this time the melting of the glaciers would have raised sea levels enough so that Beringia would be submerged.

If humans arrived in the Americas earlier than the 15,000 to 9,000 BC window would have allowed, they could not have made the trek southward on foot.

“Pushing the arrival of humans in North America back to over 30,000 years ago would mean that humans were already in North America prior to the period of the Last Glacial Maximum, when the Ice Age was at its absolute worst,” Somerville explained.

“Large parts of North America would have been inhospitable to human populations. The glaciers would have completely blocked any passage over land coming from Alaska and Canada, which means people probably would have had to come to the Americas by boats down the Pacific coast.”

Somerville is not the first to suggest that early Eurasian migrants came to the Americas by boat. Other archaeological findings have produced evidence suggesting people were living in the Americas several thousand years before the official date of arrival.

Groups that came earlier would not have crossed the ocean from the west. They would have taken a much shorter route, sailing southward along the Pacific coast from the area of the Bering land bridge. These early arrivals would have been closely related to those who migrated by land thousands of years later, meaning the different stages of migration would not have left vastly different genetic footprints.

It would seem the true story of how the first Native Americans came from Eurasia to the Americas is multilayered and complex . The settlement of the Americas was likely an ongoing process, and future archaeological discoveries may push the time of the earliest arrival back even further that the 30,000 BC date that is now being considered.

Top image: The entrance to Coxcatlán Cave in Mexico, where the animal bones were found that suggest the first humans in the Americas came by sea . These bones were carbon dated to nearly 20,000 years before the supposed Clovis land crossing of the Bering Strait. Source: Andrew Somerville / Iowa State University

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 4th, 2021

June 4th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: