Researchers from the Max Planck Society and the Universities of Vienna and Tübingen have found new fossilized human-like remains mixed in an assortment of bone samples taken from Siberia’s famed Denisova Cave. This includes three fragments that belonged to actual Denisovans, the much-speculated-about species that gave the cave its name. These bones will be added to the growing collection of Denisovan fossils connected to the most intriguing of all the extinct human species, which lived on the Earth at the same time as Neanderthals and early modern humans yet left such a light footprint as to be virtually undetectable.

Remarkably, these Denisovan fossils were recovered from a deep excavation layer that dated to 200,000 years in the past. These are the earliest Denisovan remains ever found, and they prove that Denisova Cave was occupied by archaic humans more than 150,000 years before modern humans reached the Siberian region following their migrations out of Africa. The analysis results of the newly discovered Denisovan fossils have been published in a study in the Nature Ecology & Evolution journal.

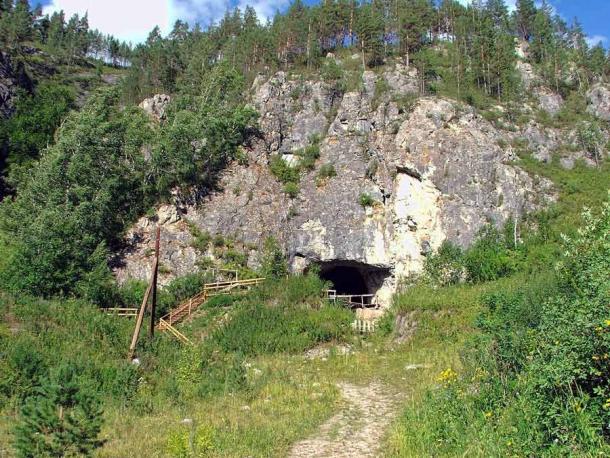

The latest Denisovan fossils were found in a deep layer of Denisova Cave in Siberian Russia and proven to date back about 200,000 years, making them the oldest Denisovan remains ever found. (Демин Алексей Барнаул / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Evidence Found In a Haystack of Denisovan Fossil Fragments

Science first learned of the existence of the Denisovans in 2008. That’s when a small number of fossilized bones and teeth were recovered from an isolated cave in the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia.

Unfortunately, the Denisovan fossil fragments found at the Denisova Cave were few. They revealed scarce details about this long-lost Homo sapiens cousin, which is believed to have died out approximately 50,000 years ago. In the years that have passed since, archaeologists and anthropologists have been frantically searching for more remains left behind by this elusive species. They’ve been searching primarily in northern, central, and eastern Asia, where traces of their DNA have been found in indigenous residents.

Archaeologists and anthropologists have been optimistic about eventually finding Denisovan fossils in these other locations (a fossilized Denisovan jawbone found in a cave in Tibet generated much excitement). But many scientists have continued to focus their search on Siberia’s Denisova Cave, where the ancient Denisovan presence has been most firmly established.

In this extraordinarily successful new study, scientists working under team leader Katerina Douka, an assistant professor in the University of Vienna’s Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, spent several years analyzing ancient DNA samples and assorted proteins extracted from approximately 3,800 bone fragments taken from the cave. As they explain in a new article in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution , these bones included a diverse mixture of animal and human fossils, and it would have been impossible to identify anything visually.

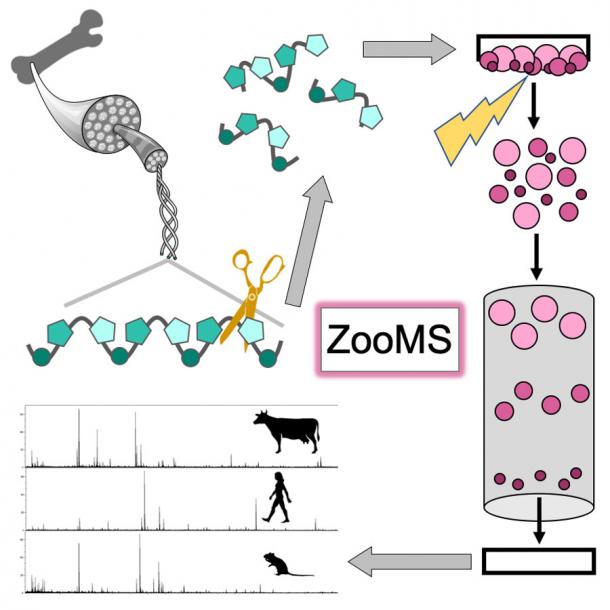

Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry or ZooMS was used to analyze the recently discovered Denisovan fossils, which are now the oldest ever! ( protocols.io)

For a Positive ID Researchers Relied on Peptide Analysis

To make a positive ID, the researchers only option was to use a technology known as Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectroscopy, or ZooMS. This high-tech tool can identify peptides (strings of amino acids) that are found specifically in the human body, and in the body of human ancestor species as well.

With this reliable technology at their disposal, the scientists concentrated on fossils excavated from the cave’s most ancient layer, which had been dated back 200,000 years. The bones collected from this layer were truly a fragmented and haphazard jumble, and that’s why little work had been done on them in the past. But with ZooMS, there was an opportunity to search for Denisovan fossils in a collection of bones that had not been fully examined before.

Team member Samantha Brown, a doctoral student at the University of Tubingen, was assigned the task of performing the actual analysis of the approximately 3,800 previously unidentified bone fragments. The vast majority of these fossil bones had belonged to animals, making the search for human remains the equivalent of looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

With enough time and diligence, even the smallest needle can be found eventually, and Brown’s research ultimately proved successful. Aided by the precise ZooMS technology, she found five bones with collagen profiles that matched those of humans.

But which types of humans? Certainly not modern humans ( Homo sapiens ), which would not arrive in Siberia until much later. That left Neanderthals and Denisovans as the two possible candidates.

To solve this mystery, the scientists turned to another high-tech innovation that has revolutionized archaeological and anthropological practice: DNA analysis. Out of the five human bones Brown identified, four contained significant enough traces of genetic material to allow for a mitochondrial DNA reconstruction. These tests showed that one of the bone fragments had belonged to a Neanderthal, while the other three were all Denisovan.

At an age of 200,000 years, this DNA typing officially established the three bone samples as the oldest remains of Denisovans ever found.

“Denisova is an amazing place for DNA preservation, and we have now reconstructed genomes from some of the oldest and best-preserved human fossils,” Dr. Diyendo Massilani, a genetic researcher from the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, explained in an Institute press release announcing this amazing discovery.

The Denisova 3 fifth distal finger phalanx of 13.5-year adolescent Denisovan female, the first bone fossil uncovered at Denisova Cave in 2008. (Thilo Parg / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Finding New Denisovan Fossil Bones and Lithic Stone Tools

There is no underestimating the impact and importance of this discovery. “We were extremely excited to identify three new Denisovan bones amongst the oldest layers of Denisova Cave,” Katerina Douka told Live Science . “We specifically targeted these layers where no other human fossils were found before, and our strategy worked.”

“Finding one new human bone would have been cool, but five? This exceeded my wildest dreams,” Samantha Brown added.

The discovery of the age of the 200,00-year-old Denisovan bones was exciting. But there is another part to the story that is perhaps even more significant.

Inside the deep layer of the cave where the fossils were found, archaeologists also unearthed a large number of lithic stone artifacts dating to the same time period. These included several scaping tools, which presumably were used to process animal skins.

Notably, none of these tools were similar to any that had been found in central or northern Asia before.

“This is the first time we can be sure that Denisovans were the makers of the archaeological remains [the stone tools] we found associated with their bone fragments,” Douka confirmed.

Previously discovered Denisovan fossils had either been found separate from artifacts, or alongside artifacts that were suspected to have been left by Neanderthals. The two ancient species frequently occupied the same caves and territories and were known to have interbred .

There were also thousands of pieces of animal bones found in the oldest layer of Denisova Cave. They have now been identified as belonging to such species as deer, wild horses, bison, gazelles, and wooly rhinoceroses, all of which could have been hunted by Denisovans 200,000 years ago. Many of the bones contained marks consistent with butchering, while others had been damaged by fire (meaning the flesh of the animals had been cooked).

“The site’s strategic point in front of a water source and the entrance of a valley would have served as a great spot for hunting,” Douka noted.

If Denisova Cave contains more Denisovan bones or artifacts, the researchers intend to find them. Katerina Douka confirms that her team is continuing its search at the cave, while also carrying out excavations at several other Asian sites where they are hopeful Denisovan fossil remains might be found.

Top image: Denisovan fossils look a bit unremarkable, but these bone fragments, mostly from animals, were perfect for Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectroscopy and DNA analysis, which were used in the recent study . Source: Samantha Brown / Nature Ecology & Evolution

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 2nd, 2021

December 2nd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: