Mithras the god originated in the east, in Persia (modern day Iran) where he was first worshipped. When soldiers of the Roman Empire came back to the West they brought this cult with them and in time his cult worship spread throughout the Roman Empire, not only with the soldiers but also by the merchants who travelled into the land of the Persians.

This was unlike the religion practiced by the Christians at this time, who allowed women to be involved, while the practice of the Mithras cult with it various ceremonies was for males only. This was part of its appeal to the soldiers of Rome. Such worship was carried out in fine temples adorned with marble sculptures to Mithras along with other gods worshipped in Ancient Rome .

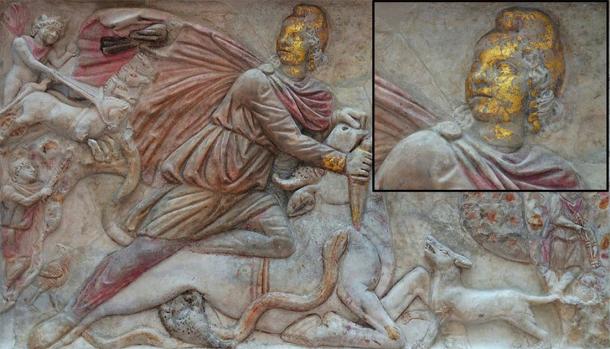

The myth of Mithras slaying the bull is represented all over Rome with several examples, such as this relief, now held at the Vatican. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Advancing the Mithras Cult

Coming from the land of Persia, Mithraism was also seen and thought of as a religion surrounded by sacred ‘Mysteries’ all being around the god Mithras. There was also another version of the god known to the Greeks, so this brought together a closer bonding of the Persian and the Greco-Roman worlds.

For those devotees of this cult – and those seeking greater knowledge – there was a strange and strict code of different tasks or grades set by the Priests of the Mithraeum that the follower had to pass if he wished to advance. Passing these would place them with the divine protection of the various gods among the planets and stars.

The devotee would need to be prepared to attend and undertake the initiations required at each grade of those seven steps. The soldier followers would meet in the temples which were mainly built underground. These temples were known as the ‘Mithraeum’ (pl. Mitheraea).

Mithraeum in lowest floor in San Clemente in Rome. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The main headquarters for this religion was in the middle of Rome, but it became so popular among the various Roman legions that it quickly spread across much of the western Roman Empire. The remains of temples have been found from Egypt in Africa to as far north as Britain on the edge of the known world.

However, the worship of the god Mithras faced growing hostility from the other emerging religions from the East, including that of Christianity. They saw it as a direct challenge to their own religion, so much so, that by the 4 th century AD the Christians were doing everything within their power to have the worship of Mithras ended as well as trying to have those who followed this cult prosecuted.

Unveiling Mithras Cult Worship

Modern research and numerous archaeological discoveries, along with artifacts and monuments have brought to life many of those ancient sites where the devotees to Mithras met. Such finds have given us much more knowledge and understanding about Mithraism and how it operated throughout the Ancient Roman Empire.

Fragment of a mosaic with Mithras. ( Walters Art Museum )

Many images and carvings that have been discovered depict Mithras emerging from a scared rock. Also many show him killing a bull which was then shared in an offering to the Sun god, Sol. It has been estimated by researchers that there was probably around close to 700 temples to Mithras within the city of Rome. One of the difficulties with studying this religion is that to date there have been no written details of the movement that have come to light. What information can be gathered on Mithras appears mainly to come from studying the physical evidence, which can in itself be problematic.

Division of Mithraic Cults

During Roman times they referred to the religion of Mithras as one of ‘ Mithraic Mysteries’ coming from the lands of Persia. So we can end up with two references; that of the Roman Mithraism (Western) while the Persian version we can call the Persian ownership of Mithras (Eastern).

In ancient Persia, ‘Mithra’ was one of the old gods. There is always debate on the exact form of the Classical Greek or Latin when it comes to saying that the Roman Latin followers named the god ‘Mithras’ but if we study what is available today to scholars we can find references to the earlier lost history of Mithras and his Mysteries come from devotional inscriptions quoting Euboleus and an author named Pallas who thought the word Mithra may have been foreign.

In Iran, ‘Mithra’ and the Sanskrit ‘Mitra’ are thought to have come from an amalgamation of Indo & Iranian as Mitra may mean covenant. Among modern day historians there exist many different ideas concerning whether these names do indeed refer to the same god. Mithras, Mithra and Mitra. Was Mithras the one god that was worshipped by perhaps the different religions and regions?

One writer and researcher considers that Mithras as we perceive him slaying the bull could have been a new god worshipped only from the start of the 1 st century AD.

Statue of Mitra sacrificing the bull. Second half of 2nd century AD. Originally found in Rome. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Venice, Italy. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

What we know about the cult of the god Mithras comes mainly from the study of both sculptures and also reliefs. In the ancient Roman Empire, the worship of Mithras is shown in the images of the god killing the bull. Of course, other images found throughout Roman temples also show Mithras entertaining the Sun god, Sol, while there are other reliefs showing the birth of Mithras by the sacred rock. However, the image that remains the most powerful for many is that of the slaying of the bull.

Mithras and the Bull

This appears to be one deliberate practice by the Romans being specific to their version of Roman Mithraism and maybe be a feature dividing the Persian and Roman traditions of the worship of this god. From the study of the Iranian god Mithra it seems the act of killing the bull may not have occurred when looking at the Eastern portrayal of the god.

When entering a Roman Mithraeum, what one usually will see is a carving or sculpture of the god Mithras slaying the bull, which is referred to as the ‘tauroctony’. Normally we see this relief of Mithras dressed in the style of clothing known as Anatolian. Also recognizable to many is the distinctive Phrygian Cap.

Large polychrome tauroctony relief shows Anatolian attire and Phrygian cap, from the Mithraeum of S. Stefano Rotondo, end of the 3rd century AD, Baths of Diocletian Museum, Rome. (Carole Raddato / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

The killing of the bull shows it as lying down, which indicates it was exhausted in its struggle for life against Mithras and he continues to stab the bull. In these sculptures, a dog and a snake plus a scorpion which is biting the bull’s testicles are also shown. Normally, a raven is also depicted, which is on or close by the bull. It is assumed from the sculptures that the bull is white. The figure of Mithras rests one knee on the back of the bull. Dressed in similar clothes are two attendants to Mithras holding the torches, whose names are recorded as Cautopates and Cautes.

Modern representation of Mithras and the bull. (Image courtesy of Janet Callender)

This whole scene, we are told, takes place in a cave into which the white bull has entered in its efforts to escape from Mithras who is determined to hunt it down. On occasions the cave is shown with the signs of the Zodiac while another marking shows the god Sol sitting upon the top entrance to the cave with the Sun’s rays shining down. Opposite can be seen the form of the Moon Goddess Luna, known by the sign of the crescent Moon.

Alternative Depictions

We can find many other carvings of Mithras, such as showing him being born upon the sacred rock as well as his association with water. In some carvings Mithras is shown holding hands with Sol and offering to share with him his meal of the slain bull. We also see him going up into heaven in a mystical chariot.

Within the Mithraeum in the city of Rome Mithras is shown as the god similar to the carvings of the Ancient Greeks heroes without any clothes on.

Rock-born Mithras and two altars dedicated to Cautes (left) and Cautopates (right), from the Mithraeum under Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome, from 180 until 192 AD, National Museum of Rome, Baths of Diocletian ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

There are other depictions shown and reliefs that concentrate upon the rich feastings of Mithras as well as that of slaying the white bull. From this, scholars of Mithras inform us that the act of slaying the bull was held at the beginning of the celebrations. In many Mithraea were to be found smaller statues of the above which devotees could use in the private prayers to Mithras. Such feasting or banqueting was all part of the ritual.

Both the Sun god and Mithras are normally seen in the hides of the dead bull. Some other scenes show us the messenger god Mercury who carries the souls from the blood which collected at the base of the altar up to heaven.

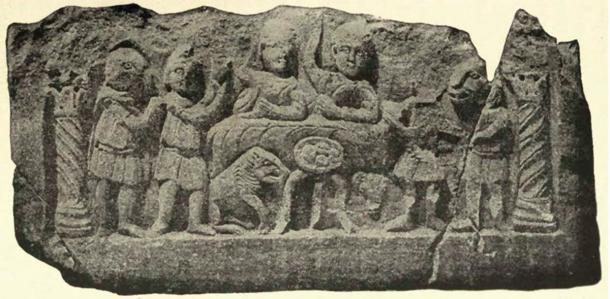

Mithraic communion, bas relief from Konjica, Bosnia showing Mithras and the sun god Sol feasting, lower rank initiates serving, four loaves of bread with crosses marked on them. ( Public Domain )

It is from the sacred rock that Mithras is said to have been born and appears on Earth as a young man with a dagger held in one hand. The only garment he is shown wearing is the Phrygian cap upon his head. But this is not the only version of the birth of Mithras. He also is depicted appearing from the sacred rock as a child holding a globe and a thunderbolt in his hands. Another depiction of Mithras shows him standing upon a fountain with water pouring from its base which some take to mean Mithras had also links to the God of the Seas and Oceans.

In other temples dedicated to Mithras and the Mysteries can be found depictions of a lion-headed figure, with a body of naked male upon which is also a serpent. The mouth of this lion-headed male is in many reliefs shown open, with him holding a scepter and sometimes standing upon the globe of the Earth. He also normally has four wings.

Left; Drawing of the ‘leontocephaline’ found at a Mithraeum in Ostia Antica, Italy. ( Public Domain ) Right; Leontocephaline, in Vatican Museum. ( CC0)

In the ancient Port of Ostia outside Rome in the Mithraeum, the four wings of the Lion-headed figure are said to depict the four seasons. On the chest area is the carving of a thunderbolt. Lying at the base of this figure can be seen the tongs and a hammer which indicates they belonged to the god Vulcan. Some inscriptions dedicated to Mithras found on altars give the name Arimanius who is thought to have been a god within the Mithras cult. There are some scholars who believe this lion-headed man was known as Chronos or Aion and this may be associated with the Zoroastrian religion.

[embedded content]

Merry Mithras Day!

Those who follow the cult of Mithras celebrate his date as being on the 25 th December each year. We can see this is interesting, for the Christians also used this date to mark the birthday of Jesus. We must remember, unlike the Christians, the celebration of the birthday of Mithras was done in private with no public ceremonies held to commemorate this mystery. Also, upon the 25 th December there was held the festival to the Sun god Sol in the ancient world and Persia.

John Richardson’s recently published book, The Romans and The Antonine Wall of Scotland , is available from Amazon.

Top image: Mithras and the bull, fresco from Temple of Mithras, Marino, Italy, dated 2nd century AD. Source: Public Domain

References

Mandelbaum, Lucas, 2016. ‘ The Axis of Mithras: Souls, salvation, and shrines across ancient Europe’ , CreateSpace Independent Publishing

Rivers, Charles, 2015. ‘ The Mysteries of Mithras: The History and Legacy of Ancient Rome’s Most Mysterious Religious Cult’, Charles River Editors, Audiobook.

Related posts:

Views: 1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 1st, 2020

September 1st, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: