The Akitu festival was one of the oldest Mesopotamian festivals, dating back to the middle of the third millennium BC. It was during this twelve-day ceremonial event, which began at the first New Moon after the Spring Equinox in March/April, that a unique tradition took place in order to humble the king and remind him of his role to serve the will of the god Marduk in order to properly provide for the community. The head priest would strip the king of his regalia and slap him hard in the face. The Babylonians believed that if the king teared up, Marduk approved him to be king for another year.

In a featured article about the ancient tradition of slapping the king, The Jerusalem Post writes: “It might be interesting to note that a great Babylonian king like Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BCE), well known in our chronicles as the destroyer of Judea and of the First Jerusalem Temple in 597 BCE, the mighty conqueror of the entire ancient world who considered himself to be the king of kings, would willingly and meekly, once a year, submit himself to such a humiliating procedure”.

Yet the ceremonial removal of the king’s power was considered a vital procedure to reaffirm the bond between the community and the gods, the community here being represented by the king in temple ritual.

This relief, from the palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (r. ca. 883-859 B.C.), depicts a king, probably Ashurnasirpal himself, and an attendant. Source: Public Domain / Met Museum

The Akitu Festival and the Rebirth of Marduk

The Akitu festival was dedicated to the rebirth of the sun god Marduk, one of the chief gods in the Babylonian pantheon, who was believed to have created the world out of chaos.

In the early 19th century BC Babylon became an independent city, yet it was overshadowed by more powerful Mesopotamian states such as Isin, Larsa, and Assyria. In the 18th century BC, Babylon grew in power and with it the cult of Marduk also gained influence, thus marking his triumph over Enlil (god of the former Mesopotamian states) and solidifying his place as head of the Babylonian pantheon.

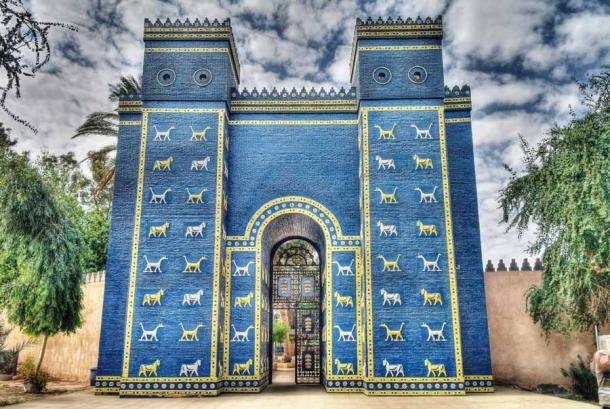

To prevent the god of chaos from regaining control, the New Year ceremony re-enacted the original victory of Marduk over the forces of destruction. It began with a great procession that included the king, members of his court, priests, and statues of the gods passed through the Ishtar Gate and along the Processional Way to the “Akitu” temple, dedicated to Marduk.

The Akitu Festival began with a great procession through the Ishtar Gate towards the temple of Marduk. Source: homocosmicos / Adobe Stock

On either the fourth day of the festival, the king was to face his trial. The high priest greeted the king before temporarily stripping him of his crown and royal insignia, and dragging him by the ears to the image of Bel, in front of whom he was required to kneel. The king was required to pray for forgiveness and to promise that he had not been neglectful of his duties.

“The list of the king’s promises and assurances was long and contained all that both clergy and the ordinary people usually demand from their ruler,” writes JPost. “It was only after the king finished this list of assurances, well prepared ahead of time, that the chief priest struck him hard upon the cheek, with an open hand but as strongly as he could. The blow had to be decisive and hard, for according to tradition tears had to flow from the king’s eyes as an indication that Bel (and his wife Beliya) were friendly, an omen which purported to assure king’s future success and the prosperity of the country.”

A steady flow of tears assured the priest and the people the king’s reign would be prosperous and his crown and royal regalia were returned to him. As well as testing the gods’ approval for his reign, the hard slap was intended to remind the king to be humble and to inspire him to remain focused on his duties and obligations towards his people and his gods.

“However, the humiliation of the king during the New Year ritual served a double purpose,” writes JPost. “It demonstrated to the king that without his crown, sword and scepter he was just another ordinary mortal, whose fate depended on the mighty gods and their humble servants.”

The Akitu festival endured throughout the Seleucid period (312 – 63 BC) and into the Roman Empire period. Roman Emperor Elagabalus (r. 218-222), who was of Syrian origin, even introduced the festival in Italy. A number of contemporary Near Eastern spring festivals still exist today. Iranians traditionally celebrate 21st March as Noruz (“New Day”).

Somewhere along the line, the king slapping tradition faded into obscurity. Nevertheless, there seems to be great value in a ceremony that humbles a nation’s leader and reminds him or her of their duty to serve their people with honour.

Featured image: Assyrian relief panel, 883–859 BC. Source: Public Domain / Met Museum

Related posts:

Views: 2

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 2nd, 2022

January 2nd, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: