Margery Kempe was, for the first 40 years of her life, an ordinary woman. Born into a middle-class family in 14th century East Anglia in England, she is remembered today for her remarkable later life as a holy woman and medieval mystic. Even though her career choice makes her interesting, as female mystics were uncommon at the time, the most remarkable thing about Margery’s life is the record she made of it in The Book of Margery Kempe . This book about her life is the earliest surviving autobiography in Middle English that we have.

The Book of Margery Kempe

Perhaps most significantly, the book is written in Margery’s own words. This was extremely rare as most women in the Middle Ages were illiterate, with any biographies of their lives being written by male authors. As the first medieval autobiographer, and as a woman, Margery Kempe has been hailed by modern scholars as a feminist heroine, and her story proclaimed as a quest for liberation and independence from the tyranny of the patriarchy.

So how did a woman of such apparent mediocrity come to be revered as a scion of the feminist cause? Was she really the brave pioneer we now consider her to be? The answer may be found in Margery’s own words.

An Ordinary Beginning

Margery was born in 1373, the daughter of John Brougham, a burgess or landowner in the town of King’s Lynn in Norfolk, known at the time as Bishop’s Lynn. It was a prosperous port town, and Margery’s father was a man well-respected within the town community who variously held many honorable positions including mayor, alderman (city councilor), member of parliament, coroner, justice of the peace and chamberlain.

Much of medieval King’s Lynn survives to this day ( Evelyn Simak / Geograph)

At the age of 20, Margery married John Kempe, a man from a family of somewhat lesser status in the community and lesser wealth than her own. Margery seems to have believed herself above such a marriage, and she says in her book that she had told her husband they should never have married because she came from “worthy kindred”.

Margery was also a businesswoman of some means herself. She describes her brewing business that she began out of “pure covetousness”, and the fashionable clothes and expensive jewelry she used to wear, presumably paid for by her business ventures.

Despite Margery’s apparent distaste for her husband however, she also says that he cared for her deeply and treated her with “tenderness and compassion”. They had 14 children together over the course of their marriage, although very little is known about them as Margery does not mention most of her children in her autobiography, beyond a few very brief references.

Virtually all we know about Margery’s life comes from her book, which has survived in a single manuscript copied from the original by a Norwich-based monk known as Richard Salthouse. Thus we have no record of when Margery died, although we know it was sometime after 1438.

The Manuscript of the Book

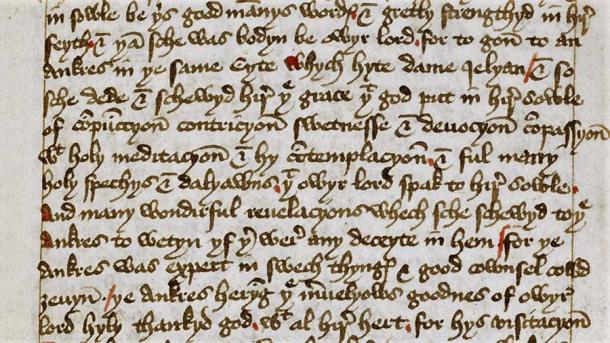

The single manuscript containing The Book of Margery Kempe was uncovered in 1934 in the private collection of the Butler-Bowdon family, and now resides in the British Library’s manuscript collection in London. The book itself was written in the 1430s, and it was written in several parts due to the death of the priest who had been transcribing it for her.

Excerpt from The Book of Margery Kempe ( Public domain / Wikimedia Commons)

Margery lived in a time when women were generally not educated, particularly those of the middle and lower classes. As a result, like most women of her time, she could neither read nor write. Many men in the late Middle Ages were also illiterate, so to write her book Margery had to rely on a priest, religious orders being a predominantly literate class during this period.

The story follows a somewhat chronological progression of her life to date, going on to discuss the breakdown of her marriage and her embarkation on a spiritual journey, both physically and psychologically. However, the story is not structured as a modern reader would expect a narrative to be, instead being episodic in form. The reason for this is explained by Margery in the preface of her book:

“A short treatise of a creature set in great pomp and pride of the world, who later was drawn to our Lord by great poverty, sickness, shame, and great reproofs in many diverse countries and places, of which tribulations some shall be shown hereafter, not in the order in which they befell, but as the creature could remember them when they were written.”

She refers to herself throughout the book as this “creature”, no doubt to reflect her humility and unworthiness. Margery also explains her reasoning for choosing to record her life, and that it was not for any kind of self-glorification but rather for the glorification of God:

“When it pleased our Lord, he commanded and charged her that she should have written down her feelings and revelations, and her form of living, so that His goodness might be known to all the world.”

It has also been suggested that Margery intended her book to act as proof of her own sanctity, and that perhaps she hoped to earn herself status as a saint, but no direct evidence of this intent exists in the book and indeed Margery Kempe was never made a saint. She was, however, commemorated by the Church and is venerated by some for her saint-like qualities.

Margery’s Spiritual Rebirth

In a somewhat poetic turn of events, the spiritual rebirth Margery experienced and documented in her book began with the birth of her first child. She describes in vivid detail, the disturbing hallucinations she experienced following this, when she “went out of her mind and was amazingly disturbed and tormented with spirits for half a year”:

“Devils opening their mouths all alight with burning flames of fire, as if they would have swallowed her in, sometimes pawing at her, sometimes threatening her, sometimes pulling her and hauling her about both night and day.”

Illumination of a religious vision, Book of Hours of Simon de Varie, 15th Century ( Public domain / Wikimedia Commons)

These visions caused Margery such distress that she “bit her own hand so violently that the mark could be seen for the rest of her life” and she “pitilessly tore the skin on her body near her heart with her nails … and she would have done something worse, except that she was tied up and forcibly restrained”.

Through her trials and torments, Margery had forsaken her faith and denied her God. However, Jesus Christ came to her in one of her visions as a man clad in a purple mantle, sitting on her bed and asking her why she had forsaken him, and with this Margery grew calm and regained her reason. She began to return to the ordinary routine of her life, but her revelation had shocked her so much that Margery determined not to return to her former prideful and covetous ways.

The Vow of Chastity

Unfortunately for her husband, Margery also lost her desire for sexual intercourse and decided that the carnal act had become so abominable to her that she would rather “have eaten and drunk the ooze and the muck in the gutter than consent to intercourse”. For a spiritually-minded person in the Middle Ages, sex was considered unsuitable even within marriage, which is doubtless why Margery found herself disinterested in it after her spiritual rebirth.

Her husband however was evidently displeased when she expressed her desire to “live in chastity”, and Margery describes how she was forced to have sex with her husband “with much weeping and sorrowing”. During the medieval period, rape within marriage was not considered a crime, and so Margery had to endure this treatment for 3 years.

Vows of chastity were not uncommon in medieval England ( inarik / Adobe Stock)

Being a clever woman, Margery eventually found a way to convince her husband to grant her the chastity she desired by making a deal with him. On a Friday, Midsummer’s Eve, Margery and John were travelling to Bridlington and stopped at a cross by the roadside. John denied Margery’s request that she take a vow of chastity, but proposed a deal that if Margery were to still share his bed, pay off his debts, and eat meals with him on subsequent Fridays, then he would agree not to have sex with her. Margery had been fasting on Fridays for some time, as part of her religious devotions, and so she was torn over whether or not to accept her husband’s proposal.

After praying in the field nearby, God spoke to her and commanded her to cease her fasting so that she may be granted her wish. Margery returned to her husband and said that if he agreed to “never make any claim on me requesting any conjugal debt after this day as long as you live”, she would pay his debts and eat meals with him as he wished.

Within the next year or so, John himself had taken a vow of chastity and the marriage seems to have remained amicable. When John later suffered a debilitating illness that eventually led to his death in 1431, Margery was his sole carer in the final years of his life.

Mystic, Pilgrim, Heretic

Margery’s spiritual vocation as a medieval mystic was unusual for a woman of her social class, and it was also controversial at that time for a woman to engage in mysticism or any religious vocation outside of the established institutions.

Since ancient times, there has always been suspicion surrounding religious women who were not enclosed, either in nunneries or as “anchoresses” – women who walled themselves into a cell secluded from the outside world so that they may devote themselves to prayer and contemplation, such as the famous Julian of Norwich.

Julian of Norwich ( Amitchell125 / Wikimedia Commons)

In the 14th century, England had no established tradition of “ singular” religious women. This made Margery an anomaly, and as such she represented a threat to the social structures of society. This is probably why she often experienced anxiety about the validity of her spiritual convictions, and also found herself the victim of scorn and persecution.

During a visit to Canterbury, Margery was “greatly despised and reproved” by the monks and priests there because of her excessive weeping, so much that her husband felt ashamed and acted as if he did not know her. The religious men condemned her for not being “enclosed in a house of stone, so that no one should speak with you”.

When Margery spoke up to defend herself, she was chased out of the monastery by the men who shouted that she would be burned as a heretic. She was saved by two kindly young men passing by, who escorted her back to the inn where she was staying, and where her husband was waiting.

An ancient mystic ( Rainer Fuhrmann / Adobe Stock)

By the 15th century, more and more people (mostly men) were choosing to follow the path of mysticism. This left many of them open to accusations of heresy as it bypassed the conventional spiritual pathways endorsed by the Church. Some medieval mystics deliberately moved away from the teachings of the Church, but Margery saw her spiritual path as being aligned with Church doctrine, and often reiterates in her book her obedience to orthodoxy. Margery was tried for heresy several times throughout her life, but was never convicted.

Margery’s Religion

Despite her lack of formal education, Margery taught herself about Christianity by engaging monks and other religious men to come to her house and read to her, so she was intimately familiar with all the foremost works of Christian authors of her time. She was also familiar with many works about other female mystics, and Margery emulated these women in her own practice when she took up her vocation as mystic.

St Bridget of Sweden and Mary of Oignies were particularly inspiring to her and no doubt some of her religious beliefs were due to their influence. Her desire to pursue chastity within her marriage, her pilgrimage to the Holy Land, her fasting and her copious weeping, were all likely as a result of their teachings and example.

Margery Kempe was known to be many things to many people throughout her life – daughter, wife, mother, businesswoman, madwoman, heretic, and saint, to name a few. Although she may have begun her life as an ordinary woman, following the conventions and expectations set out for her by society, Margery’s personal spiritual convictions and her sense of determination led her to diverge from conventional pathways and forge her own way ahead in the world.

Margery would by no means have considered herself to be a feminist or a pioneer of any sort, but it is evident from the book she wrote about her own life that she was indeed a very brave woman who faced a multitude of challenges in her life, always with tenacity, courage, and single-minded purpose.

Top Image: Margery Kempe defied social expectations and wrote the earliest surviving autobiography in English. Source: Petro / Adobe Stock

By Meagan Dickerson

References

Atkinson, Clarissa W. 1985. Mystic and pilgrim: the book and the world of Margery Kempe . Cornell University Press.

Baker, Derek, editor. 1978. Medieval Women . Oxford: Blackwell.

Kempe, Margery. The Book of Margery Kempe . Translated by B. A. Windeatt. 1994. Penguin Books.

Powell, Raymond A. 2003. “Margery Kempe: An Exemplar of Late Medieval English Piety.” The Catholic Historical Review 89.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 10th, 2021

May 10th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: