The Inquisition is normally associated with the ardent renegades of the Renaissance who preferred to die defending science and humanism than go along with the religious dogma that persecuted free-thinking. Much literature, television and theatre has been dedicated to the hundreds of years that saw healers, scientists and philosophers vilified and prosecuted for having beliefs contrary to the doctrine of the Catholic Church. The Campo de’ Fiori in Rome, with its market stalls and little cafes, seems far removed from the past that saw famous heretics executed and books burned in its center. Only the statue of Giordano Bruno gives visitors a clue to its unedifying history.

However, the Inquisition didn’t just target the intellectual and the infamous. In fact, it spent a lot of time presiding over cases brought by squabbling neighbors, families who needed to fix a scandalous reputation and husbands and wives in a state of marital discord. In Malta during the early modern period, magic, blasphemy and apostasy were common in everyday society and the Inquisition was there to reign it all in.

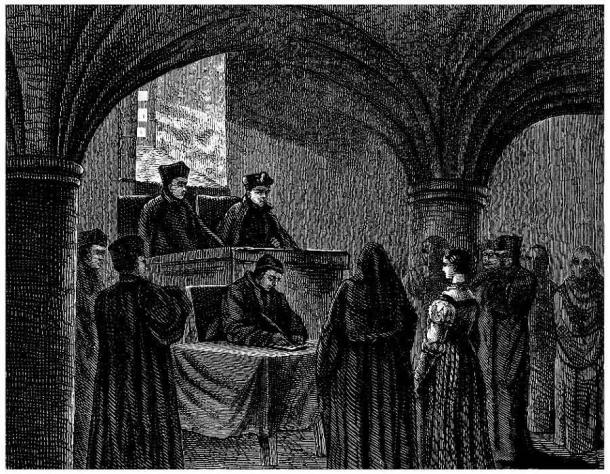

Tribunal, Inquisitor’s palace in Vittoriosa (Birgu), Malta. (Marie-Lan Nguyen/ CC BY 2.5 )

Otherworldly Explanations

Much of the research conducted by experts in the Cathedral Archives has culminated in some wonderfully illuminating studies into life in early modern Malta. A picture emerges of complex societal relationships and tensions where magic and witches serve as convenient explanations or excuses. Take for example the case of Domenico Carceppo who discovered that his supposedly virginal sister-in-law was in a sexual relationship with a local doctor. He was quite sure Lauria would never have freely entered into such an immoral arrangement.

In an effort to protect her reputation and cast the blame for her behavior elsewhere, Domenico accused a woman named Margarita of using witchcraft to bring about the situation on behalf of the doctor. This clever move took away any insinuation of impropriety on the part of his sister-in-law. The same Margarita struggled to stay out of the occult spotlight. She also got the blame for bewitching Damiano Cassar on the orders of his sexual partner Agatha to make sure he was impotent around other women!

Controlling Cupid

Potions and the witches behind them were in great demand for love magic. Both men and women were in the habit of trying to give their love lives a bit of extra luck. A Gioseppe Farrugia was reported for using occult services every time he decided he was in love, a move which apparently worked with two women, one of whom was married, the other single.

A witch creating a love potion. ( kharchenkoirina /Adobe Stock)

Whilst many wives used magic to prevent or stop their husbands from cheating, others used it to help themselves find suitable extramarital suitors and to prolong illicit affairs. A Teresa from the village of Balzan even procured magic to keep her sexual relationship with a priest afloat. Single women saw magic as a route to finding a good match, but for many women in bad marriages, it was a way of redressing the imbalance in their relationships. There are reports of women using magic to stop their husbands from committing domestic violence, from drinking too much, from leaving them permanently for a mistress and from gambling.

Love potions weren’t the only tools used to summon supernatural assistance. Talismans, charms and incantations were all seen as effective ways of controlling love and sex. Although, rather bizarrely, the term magnetic attraction was taken quite literally in early modern Malta. Actual iron magnets were sometimes used to ensnare a love interest.

Conjuring Money Spirits

If magic had any efficacy at all than it must surely have been neutralized when the other party was dabbling with it as well. Men popularly used magic for monetary gain and this often applied to gambling. Wives might have been running around trying to conjure up occult forces that could stop their husband betting all the household money away, but men were using the same magic to help them win. Blasphemy was much frowned upon by the Inquisition and a lot of the men brought before them had been driven to swearing by their bad luck at the gambling tables and financial difficulties in general.

Treasure hunting was also a fashionable way of making money from the 16th century onwards. After applying for a license, all a person needed to do was start searching. But it was quite common for people to boost their efforts with a little divinatory magic. From using black magic books to enlisting the help of sorcerers, many treasure hunters were denounced for the methods they used to secure a find. It seems that some sorcerers didn’t really believe they had such specialist skills, but pretended to know how to divine for financial gain.

Curing the ‘Evil Eye’

Belief in the evil eye is very common in the Mediterranean. Those who have the ‘eye’ are thought to give bad luck unintentionally to anything or anyone that they are envious of. Rather than a curse, it’s an accidental kind of misfortune and many people think of themselves as being capable of possessing it. Simply congratulating someone or admiring a possession of a neighbor can cause a calamity to occur if it isn’t followed by a blessing.

The belief dates back to ancient times and the Inquisition had a number of reports related to the evil eye to handle. One lady was reported for trying to remove the evil eye from her brother with the help of a witch, potions and incantations. Her reason for assuming him to be under the envious influence of the evil eye was his addiction to prostitutes and the enormous amount of money he spent on them.

A typical Maltese boat called luzzu has the symbol of the eye known as “l-għajn,” which is said to protect fishermen from storms and malicious intentions. (-jkb-/ CC BY-SA 3.0 )

This wasn’t the only time the evil eye got the blame for turning a man away from his wife or the prospect of marriage, with the subsequent attempt to cure the affliction raising red flags to the Inquisition. Illness was also often thought to be caused by the evil eye and healers were very busy plying their trade which combined religious prayers with pagan practices, therefore still falling foul of the Inquisition.

High Stakes but no Fire

Popular fiction certainly makes it look as though reading forbidden books and talking about taboo subjects was the fastest way to a fiery death under the Inquisition. However, the day-to-day reality of early modern Malta wasn’t quite so treacherous. The Inquisitors were more concerned with reform than retribution.

Heretics were usually given sentences that forced them back into a religious way of life with prescribed times to say prayers, hear mass, fast and recite psalms. They were sometimes expected to pay fines, give alms, go to prison or endure house arrest on top of their religious obligations. Public repentance was often a part of the punishment with sentences specifying that a heretic wear a certain kind of habit that marked out their sin for life, denounce heresy in front of everyone and kneel throughout mass in full view of the congregation.

Painting by Francisco Goya depicting an auto de fé, an act of public penance carried out between the 15th and 19th centuries of condemned heretics and apostates imposed by the Inquisition. ( Public Domain )

They were also duty-bound to report other heretics. People from lots of different backgrounds found themselves in trouble with the Inquisition. Peasants, silversmiths, corsairs, doctors, lawyers, judges, priests and slaves were all accused of heresy.

Maintaining the Moral Order

Those most at risk of being denounced as witches by their local community were those that lived somewhat on the edge of society. Widows and prostitutes survived independently from men and were therefore without protection and supervision at a time when society expected them to play a clearly defined role in relation to their husbands. There are many reports of prostitutes being reported not just because of their immoral occupation, but because of the witchcraft they supposedly practiced alongside it. Sometimes, suspicion even fell on midwives who moved around nocturnally because of their occupation. It was not socially acceptable for women to be outside at night.

A woman before a tribunal of the Inquisition. ( Erica Guilane-Nachez /Adobe Stock)

Anyone with an immoral reputation could attract the animosity of their neighbors who were encouraged to look out for and report heretical behavior. One alleged witch was convinced her reputation was rooted in a daring but public escape from her violent husband. Climbing from a terrace in a disheveled state whilst making the sign of the cross immediately gave her the notoriety of a witch.

But it wasn’t just neighbors whose denunciations the Inquisition would hear. People also reported themselves, sometimes starting with the parish priest. Confession was encouraged but sometimes rejected if the priest thought the sinful person needed to be referred to the Inquisition instead.

Harmless Beliefs

Reading about the Inquisition, a person in the 21st century might be inclined to think there was a lot of fuss about nothing. These days many people are drawn to spiritual beliefs outside of organized religion, astrology and tarot reading are seen as harmless, and in this scientific age, atheism is also very popular. None of this particularly upsets society.

But in the early modern period societal structures were wildly different and people were expected to live a moral life in a specific role. The range of problems reported to the Inquisition show just how hard it was to keep everyone in check.

Magic was used to many diverse ends including to find love, to stop cheating, to prevent violence, to find treasure, to heal illness and to win at gambling. Reading forbidden books, discussing alternative beliefs and avoiding church was the behavioral pattern of an outrageous heretic.

In modern times people often don’t know their neighbors. In the times of the Inquisition simply having a bad relationship with them was enough to get a person reported. Everyone had to lead a careful, morally impeccable life and they had to do it in full view of their local community to ensure a good reputation. It must have been quite exhausting and relatively easy to make a mistake.

Top Image: A monk inquisitor. Source: Shaman-foto /Adobe Stock

By MegalithHunter (Laura Tabone)

References

Berger, A., 2011. The evil eye: A cautious look. Journal of Religion and Health , 52 (3) pp.785-788.

Moss, L. W. and Cappannari, S. C., 1976. The Mediterranean. Mal’occhio, Ayin ha ra, Oculus fascinus, Judenblick: The Evil Eye Hovers Above. In: C. Maloney, ed. 1976. The evil eye . New York: Columbia University Press. Ch.1.

Camenzuli, A. (1999). Maltese social and cultural values in perspective: confessions, accusations and the Inquisition Tribunal, 1771-1798 (Master’s dissertation). https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/73034

Cassar, C (1990), ‘An index of the Inquisition: 1546 – 1575. Hyphen, vol. 6, no.4, pp. 165-178. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/25125

Cassar, C. (1996). Witchcraft, sorcery and the Inquisition: a study of cultural values in early modern Malta. Malta: Minerva.

Cassar, C. (2004). Magic, heresy and the broom riding midwife witch – the Inquisition trial of Isabetta Caruana. Proceedings of History Week 2003 , 25-41. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/22298

Ciappara, F. (1998). Society and the Inquisition in Malta, 1743-1798 (Ph.D. dissertation). https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/13187

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 19th, 2021

September 19th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: