Gottfried P. Dulias: Surviving the Soviet Gulag

by Gottfried P. Dulias

Published August 8, 2016

Gottfried P. Dulias was a young Luftwaffe pilot who had seen plenty of action in the skies above the Eastern Front. Flying the Messerschmitt Me-109G-14/AS with Jagdgeschwader 53—known as the Pik A’s, or Ace of Spades squadron, or simply as JG 53—he shot down five enemy aircraft and became an ace.

Subsequently, he was shot down by ground fire and captured, and he spent three years in a Soviet prison camp. Dulias emigrated to the United States in 1953 and worked in residential construction and as a locksmith until his retirement in 2009. He and his wife, Hedwig, were married for 46 years until her death in 1997.

The father of three daughters, who also has two grandchildren and one great grandchild, Mr. Dulias lives today in Patchogue, New York. He and coauthor Dianna M. Popp met on the internet and later worked together to produce the book Another Bowl of Kapusta, from which this story is excerpted. Kapusta is Russian for cabbage soup, which served as a staple food for prisoners of war held by the Soviet Union.

Captured Near the Crackling ‘Gustav’

As I was passing over the front line with tracers flying by right in front of me, I had no time for evasive action and I heard loud pings hitting my engine and saw the impacts and some debris hitting my windshield. The engine started to sputter as the cockpit immediately filled up with smoke, and I knew I was doomed. The first thing I did was to jettison my canopy in order to see and breathe. I quickly searched for a suitable spot to make a belly landing. Luckily, I found a clear opening in the forested area and set my mortally wounded machine down on the snow-covered ground.

Gottfried P. Dulias

Coming to a stop, I made a quick exit, ran away from my beloved “Gustav,” and within a split second it blew up. Immediately, I headed toward the nearby woods to hide. Following my training on the procedures for bailing out, I used my survival knife and dug a small hole in the ground to hide my documents, including a photo of me in civilian clothes from my last furlough wearing the National Socialist party pin. I intended to hide in the woods until nightfall and hoped to make it back through the nearby front line. I still heard the crackle of exploding ammunition from my burning Me-109; it was my beloved Gustav’s goodbye call.

I started walking by feeling my way through the thick underbrush. I did have a survival compass which had glow-in-the-dark directional points and a glowing needlepoint top indicator. Besides that, I had my survival pocketknife and my Luger [pistol] with 30 bullets. I continued to grope my way through the forest, and it never seemed to end.

It was now beginning to dawn. I remained in hiding there in the forest and heard some voices. Russian was being spoken. I found a secure place and hid in the underbrush. I peeked through the branches and saw a group of six drunken Russians passing by. They passed perhaps 20 feet from me. I saw that they were soldiers, not civilians, and they walked along a narrow path. I carefully observed their movement and then managed to advance forward on my way back toward our side.

As I kept stalking in the direction of the front, following my compass, and snuck past them, another troop came along, and they spotted me. They yelled: “Stoi, Stoi!” meaning Halt, Stop! Unfortunately they spotted me before I did them. I guess I was better at navigating up in the air than on the ground! I had to hold my hands extended and outstretched above my head. They shouted commands in Russian to me that I much later got to know as derogative curses.

They were a mean bunch and I knew that they hated the Luftwaffe because of the great damage that was done to them by us. It was known that downed Luftwaffe pilots were executed on the spot. They all pointed their Tommy guns [machine pistols] directly at me. Then one started talking and sounded as he was giving me orders.

I knew he was extremely angry as he was shouting at me, obviously due to the fact that we had a language barrier. I couldn’t understand a single word. He began hitting me in the chest with his gun butt. I almost fell backwards and his stroke took my breath away. He motioned for me to walk and pointed to the direction they came from. As I passed him, he kicked me hard in the back, and I almost fell forward. As I stumbled, the others cursed me too, and then hit me with their gun butts. Finally, I got knocked to the ground, yet they continued hitting, kicking, and trampling me so hard that I almost passed out.

A Fluent Russian Major

They probably would have killed me if a Russian major had not come up and stopped them. He was a most impressive character. To my complete surprise, when he and I met face to face he addressed me in fluent German without the slightest accent. At the same time he spoke Russian to his soldiers. Thanks to God he appeared just in time to spare me from certain death.

The first thing he asked me was, “Are you the pilot of the plane that went down?”

I confirmed with a “Yes.”

He stretched his arm forward with an open hand and he said, “Give me your gun!”

I handed him my belt and holster containing my Luger. He slid the holster off my belt and handed the belt back to me. I believe he was from the same troops that were doing the ground fire that shot me down and now had searched and finally spotted me. I acknowledged his questions and was really impressed with the major’s command of the German language.

He asked me my name and rank and saw that I was a Leutnant [lieutenant]. He also asked what type of aircraft I flew, although it appeared that he was knowledgeable about that already. He ordered me to march ahead of him to their field command station, which was just beyond the forested area, to the north. I walked ahead while the soldiers still continued cursing at me, but the major gave them orders to stop that.

Later, at the farmhouse, which I correctly assumed to be their post, one of the Russian soldiers approached me, pointed toward his wrist and shouted, “Ura, Ura.” He pointed to a chain hanging out from my pants pocket. I happened to have my grandfather Dulias’s open pocket watch on me. It was of a copper-golden tone but without a cover. So I had to give him the watch. He held it to his ear, listened to it tick and shouted, “Ura, Ura.” with a smiling face, obviously happy to get that trophy. In return he gave me a piece of bread. He was friendly, not too demanding, not stern, but just had to have my watch. Perhaps it was a novelty to him that he had only heard about.

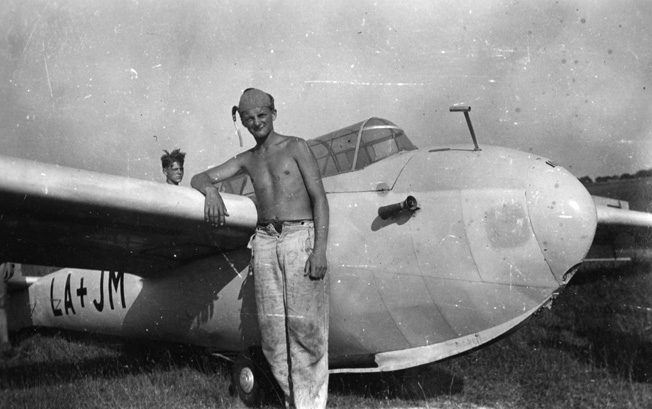

This replica of the Me-109 Dulias was flying when he was shot down provides an appreciation of the sleek lines of the fighter and displays the extensive Luftwaffe camouflage scheme that was popular at the time.

At that station I saw several German infantrymen also held as prisoners of war. They were guarded by a few Russians and were not mistreated in any way. For the first time I saw a few female Russian soldiers holding their guns. When they saw me they shouted out, “Fritz, Fritz,” which was their nickname for any captured German soldier, as I found out later. In turn, the German nickname for the Russians was “Ivan.”

The major went into this command post. One by one all newly captured POWs were called into the post to be interrogated by the major. I was asked if I knew of any more German outfits (tanks, artillery, and so on) at or near the front. I couldn’t answer, due to my real lack of knowledge. Basically all I revealed was the fact that from the air I saw some German tank columns approaching the front.

I was then asked if I was able to draw maps. I knew I was skilled in doing that because I had already been copying maps for our own pilots because of a shortage; supplies had dwindled fast and replacements never made it to our field base. So he led me to an empty desk in the room where Russian soldiers were busy working on copying maps and showed me what he wanted me to do. So now, I had to do for the enemy what I originally did for my fellow pilots; but now I had no choice in the matter.

A First Taste of Kapusta

Finally toward evening they gave me something to eat, as it was their suppertime.

A bowl of cabbage soup was my first meal as “guest” of the Russians. They called it kapusta. I welcomed that warm soup, especially after not having had any food at all since leaving my base the day before. In the rush of leaving my plane I had forgotten to take my emergency rations with me. The kapusta was rich with lots of green cabbage leaves and included some potatoes and a few other vegetables along with some morsels of meat. It tasted really good and reminded me of the good Kohlsuppe (cabbage soup) we had often at home as my mother had cooked it.

Later that night I was led to the adjoining barn where I joined the other POWs. I was shown the floor as my place to sleep. It was rather barren except for some straw, and I fell asleep in my flight suit. I slept all through the night. In the morning my whole body was hurting me from the gun-butt blows and kicks I had suffered.

The next morning, the soldier who took my watch came back to me and said: “Ura kaput, ura kaput!” He showed me that he thought the watch was broken. He looked at me with a sad face as he handed it to me. I quickly realized that he didn’t know that he had to wind it to make it go on ticking. So I wound it for him and handed it back. He held it to his ear and smiled and grinned and looked like he was dancing for joy as he shouted: “Ura karascholl, ura karascholl,” meaning, the watch worked again and that it was okay.

Then another guard came and motioned to me to come out and walk ahead of him while he remained behind me, pointing his gun at me and swinging it in the direction he wanted me to go, toward an open field. I wondered why he walked so far behind me and also noticed that he followed in my exact footprints along the open field, like Indians did on a warpath. At any moment I really expected to be shot from behind.

I kept walking but nothing happened until we reached the obviously intended destination. To my great relief we came to another farmhouse. Once there I noticed a group of about 80 German prisoners, all infantrymen. One of those Germans pointed to the field and asked me if I had come across it to get there. To my horror, he told me that I had crossed a minefield. I almost passed out from that shock.

A Long and Deadly March

More POWs were herded into our group. For a roll call we had to form three lines. We were then counted two and three times as a guard walked down the lines counting and writing in a notebook. Then we were ordered to march toward the south, away from the front. Following our column were four horse-drawn supply wagons loaded with kapusta and captured German Komissbrot [Army bread] and other supplies that were covered with canvas sheets. Following those wagons was another team of horses pulling a German Goulaschkanone [field kitchen, aka Goulash cannon].

Those infantry POWs each had their army-issued Kochgeschirr [aluminum cooking and eating dish] and their army spoon-fork combos, which were not confiscated from them as were most other things they carried. Also they could keep their army Brotbeutel [bread sacks with shoulder straps]. I did not have any of that equipment and was hoping I could borrow from one of those who were fed first whenever we stopped to eat, or I would go hungry. I did get to borrow these.

The next morning the guards shouted: “Pajyom, Pajyom!” Get up, let’s go, let’s go! Three or four of the wounded and sick POWs did not get up. They were dead. The guards just left them there in the field. After being counted again several times, we marched on the muddy road. The snow was melting and puddles were everywhere. Our march was leading us into the hinterland, far beyond the front. While under way, some of the sick and wounded were unable to continue or had passed out. They just dropped where they were in the marching column and were dragged to the side of the road by a guard and shot on the spot.

From one of those poor dead fellows I took an army-issue bread bag. It had a looped strap to easily sling over my shoulder. Inside the bag I found a shawl, a pair of socks, and some army newspapers. The shawl and socks came in handy for the cold nights and windy days. We continued marching all day long without food. At nightfall there was another roll call, and our numbers got smaller. In the evenings we got our now familiar kapusta and bread. That soup was about the same quality as what I was served the first time at the command post, not bad! And the thick slice of German Komissbrot was welcomed as filler.

Under the watchful eye of a single Red Army infantryman, a group of German prisoners passes a demolished railway bridge and splashes across a small stream on the Eastern Front.

On the third or fourth night of our march, the guards happened to find an abandoned farmhouse with a barn and stable. That was the first night we found shelter with a place to sleep under a roof. It was a welcome relief after so much marching and sleeping out in the open. I was lucky to be assigned to stay in the main farmhouse and it was still fully furnished.

We slept on the floor and while I was lying there I looked around the room. My eyes gazed upon a collection of books on a bookshelf right by my head, and that sparked my curiosity. I was able to read the spine from one of them printed in gold letters. It looked quite familiar to me: Altes und Neues Testament Die Heilige Bibel (Old and New Testament the Holy Bible)

.I slipped it off the shelf and opened it up. It was completely printed in the German language, and on the first blank page I saw a handwritten dedication by a father to his son. I don’t remember their names, but as I recall, it was in a neat handwriting in the old German Sütterlin type, that I had learned at public school.

The pages of the Bible were rather thin and were edged in gold. I decided to keep my find. It fit nicely into my bread bag. The size of the Bible was about eight inches wide by 10 inches in length, and had a spine about two inches thick. Besides that, I found a small black and white photo, which showed a quaint town with its church tower with an arched gate, along with a few blank pages of paper from a notebook. I took those along too.

Trading Boots

The next morning, after only one night of shelter, there was the usual roll call, and then we continued marching on. Every day more and more men died of their wounds; some of the weak guys who could not go on were shot where they dropped. Some were bleeding to death. Others who were never treated for their injuries had developed gangrene. It was a pitiful sight but there was no turning away from it, and I cooperated in every way, just to survive. The dead could not be buried. The ground was still frozen hard underneath the melting snow and thin layer of mud.

On our way we saw the bloated carcasses of horses lying frozen on the side of the road among burned-out Russian and German tanks, trucks, and other vehicles. Frozen soldiers, both Russian and German, were sticking out of the melting snow. It was a gruesome sight as we marched on.

One of the guards pulled me from our group and motioned me to sit down at the side of the road. I surely assumed again that I would be shot. He pointed to my fur-lined flight boots and said something in Russian, gesturing by pointing to himself. Much relieved, I realized he only wanted my boots. He removed his well-worn ones and slipped into mine. Satisfied with the obvious fit, he handed me his pair to put on. Surprisingly, they fit me too and I was glad that this exchange was all he wanted.

He shouted, and I got up and rejoined our marching column. I did not mind the holes in my “new” boots because I was still alive. Later, he handed me a big piece of Komissbrot and a handful of tobacco (machorka). Pointing to my boots, he smilingly asked: “Karascholl?” (It’s OK?) I nodded and smiled back at him, so relieved to still be alive.

The Cattle Cars to the Gulags

The “death march” lasted about a week, maybe more, I cannot remember. Finally, we arrived at Jasbereni, a town south of Budapest, Hungary, where the Russians had changed the width of the European rails to their wider railroad system. At the railroad station was a long train of cattle cars waiting for us. We found many hundreds of other German soldiers already loaded into it. The empty train came from Russia, and when not in use to transport prisoners, it was used to reload and transport dismantled German and Hungarian factories that came to Jasbereni. The machinery, parts, and supplies were loaded onto their trains to be transported to Russia.

Each of our cattle cars had been loaded with 100 soldiers. We entered them from sliding doors that were in the center of both sides of the cars. As you looked in, to the right and to the left, there were something like wooden platforms, or berths built about four feet up from the wooden floor. All four berths had a thin layer of straw as mattresses. The upper berths were centered between the floor and the eight-foot ceiling. Twenty-five men were packed in each berth, 50 on each side of the car.

In the middle space, about eight feet between the two sides, stood a potbelly stove that had a chimney pipe going straight through the roof. A small metal bin filled with black coal was near the stove and a small pile of firewood next to it. Through an opening of about six inches was a sort of gutter mounted in a downward angle, sticking out a few inches from the side of the car. It protruded about two feet inside and a little over two feet above the floor. Believe it or not, that was our toilet!

Each cattle car had one guard riding along with us. He of course had his sleeping place next to the warm stove and also had blankets to keep him warm. Next to the passenger car there were three flatbed cars loaded with a German field kitchen and a shed for the cooks and supplies. Whenever our train stopped for the night we were fed our familiar kapusta and bread.

In the meantime, I had acquired one of the German Kochgeschirr containers and a set of the spoon-fork combos from one of the poor dead POWs. I could now stand in line and get my kapusta without having to ask someone to lend me his set.

And so the days and nights went by. We had lost track of time and now never knew what day of the week it was.

Along the rail route more and more transports of factory equipment were passing us on the way deep into Russia. We rolled mostly at night because during the day our train was held at the stations’ sidetracks so that those priority transports could go ahead of us. Because of all the delays, I estimate that the trip took six to eight weeks.

The Camp

We POWs counted ourselves lucky to get a steady diet of Komissbrot as well as kapusta while on that transport. It must have been the very beginning of May when we reached our destination. The train was unloaded at Grüntal (Greendale) near Penza-oblast (Pensa), a town and big railroad station located on the Volga River in the Kazan region. We were marched to the POW camp, or gulag, just outside town.

A high barbed-wire fence was the boundary line of the prison camp. Our living quarters consisted of a stable-like post and beam structure located halfway underground in dug-out trenches about 50 feet long. They were about six feet below ground level and about 15 feet wide.

A roof starting at ground level and angling up at about 30 degrees was built over them with tree trunks packed side by side, and the cracks between them were stuffed with moss. A layer of straw and branches had been placed on top. It was then finished off with a layer of topsoil about one foot thick. The disadvantage of this style of structure was that during a heavy rainstorm some water seeped through. In the winter, the roof became frozen and was watertight.

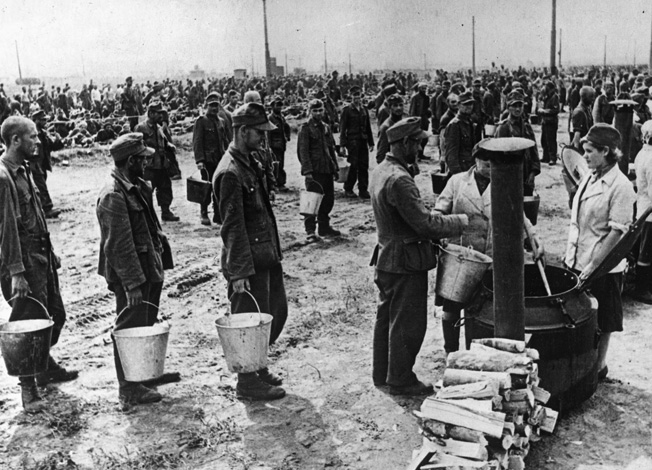

During transit to an internment camp, German prisoners line up to receive a meal from a Red Army field kitchen near Moscow in July 1944.The sheer number of German prisoners needing food and shelter stretched Soviet resources. Note that two of the cooks are women.

At both open ends of the trench there were steps leading down into our bunkhouse. Heavy canvas sheets hung as end walls and doors. Inside on both sides there were posts with girders supporting the roof logs. Large two-story bunks made of wooden planks and crosspieces had been built between and attached to those posts, accommodating about 10 POWs.

There was no provision to heat our bunkhouse, so we had to rely on our own body heat. At first not more than three army blankets were provided to cover 10 prisoners. About one hundred men filled that entire “barrack” or bunkhouse. Later, one blanket could to be shared between every two men—five Russian army blankets on each lower and upper bunk.

In the mornings our breakfast consisted of about a half tin of kapusta that was nothing more than greenish water and sometimes a portion of kasha made from barley and like a soupy puree. The heads of cabbage that were delivered to the camp for our consumption were stripped of their limp outer green leaves, and that was what they used for our soup. The clean heads of cabbage, less their withered outer green leaves, were regularly sold on the black market by the Russians.

A Textile Worker

Our workday began at 5 am. Our first assignment was in the local textile factory. They manufactured brownish-gray woven fabric used for Russian uniforms. My first job was to pull apart the freshly sheared fleece of sheep and goats and sort them by color tones. Next we inserted them into a machine that converted the fleece into particles that would be spun into thread and then into cloth. The final products were bolts of woven woolen uniform cloth fabric. An advantage of working there was that we were served lunch because we were working with civilians. They were mostly women of German descent.

Some of the women had young children with them. I was able to speak with one little schoolboy who was maybe seven years old. I asked him if I could have something to write on. He gave me several small notebooks. Among them was one with graph paper which had squares less than one quarter of an inch in size. Another had a hardcover, and along with it a small colored red pencil. We were allowed to keep a swatch from the scraps of the newly produced fabric. I also was able to take a sewing needle and some thread that they used in a sewing machine.

We also went to the local forest and had to fell trees. We made beams which were then transported by horse-drawn wagon to the Volga River. At the riverbank we later had to build boxes like honeycombs with those log beams. These were later to be filled with rocks to prevent further erosion to the shoreline.

Back at the camp at night we were supposed to get the promised ration of 500 grams of bread. Instead, we were told we did not fulfill our required tasks, so we only got 125 grams of that lousy so-called “bread.” But we considered ourselves lucky if we got a nice crusty end piece. Each portion of bread was actually put on a scale for exact weight. Supplements were attached if the portion was under the required weight.

“The War is Over!”

On May 10, 1945, when the war in Europe ended, the camp commander gave a speech to the daily count of 4,864 prisoners. “The war is over!” he called out and promised us that we would be returning home soon. This “good news” turned to bitter disappointment as days became weeks and weeks became months and months eventually turned into years without any action or intention of sending us home. By the spring of 1946, only 348 POWs were left in our camp.

Starvation and illness took their toll on the majority of the prisoners in a very short period of time. Every day 40 or more of our comrades were found dead. The slightest onset of an illness overpowered the already weakened immune systems of the overworked POWs.

I remember, as I was lying next to an older comrade on the crowded bunk and trying to get some sleep, that he just kept coughing. I had to turn my face away from his constant coughing, while I held my breath so that I would not inhale any of his germs. I was terribly afraid that I would also get sick. When the coughing finally stopped, I fell asleep. In the morning, there was his cold, stiff body at my side, a victim of pneumonia. It was a horrible sight seeing him there with a wide-open mouth and open glazed eyes. Just terrible! This was happening all too often throughout the camp.

I wore the piece of scrap material that I could keep from the textile factory wrapped around my chest, over my shirt. Every day it was of great comfort and kept me warm. I continued to trade my portions of machorka. I was reading my Bible every day, especially my favorite books from the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. I kept the Bible and all my small possessions in my canvas bread bag.

“The Moon is Eating the Sun!”

By the late spring, we were assigned to work on the “Kolkhoz,” a state-owned farm. The land had been confiscated from the former owners who were allowed to keep their farmhouses and a small parcel of land as a backyard. Then they were forced to labor at their own land for the state and for the “common good.”

Our job was to plant seed potatoes. Our work group consisted of about 100 men, and we were ordered to form a wide line shoulder-to-shoulder. Each one of us had a shoulder bag of seed potatoes that had to be planted. We worked in unison, stepping forward foot by foot in a straight line and depositing a potato into the ground.

With a belt of ammunition around his neck, Dulias dons a Luftwaffe flak helmet and mans a double-barreled machine gun (MG 81) which has been mounted on a post for gunnery training.

While we were working, the guards were facing us from about 15 feet in front, shouting commands and cursing at us. They were watching us closely to make sure that we did not dare eat any of the potatoes. When some guys indeed ate some, they were struck hard with a gun butt and knocked down, kicked, and cursed at.

Those guards were a bunch of Barbarians. Mostly they were young Russian soldiers, fanatic communists, thoroughly indoctrinated into their system. We were always glad when we had older Russian guards. They had more compassion for us and even gave orders in a friendlier, humane manner.

One very strange incident I recall while we planted those potatoes was a total eclipse of the sun that occurred on July 5, 1945, several weeks after the war had officially ended. It was an eerie, almost total darkness that lasted for quite a few minutes. We were all awed and wondered about that occurrence. One of our older guards was evidently scared, pointing up to the sky and shouting something in Russian. A fellow POW who was fluent in Russian started to laugh hysterically and told us what that guard was shouting: “Look, look, the Moon is eating the Sun!”

Delousing

Once a month we were marched to a delousing facility. There we had to strip naked and put our uniforms and underwear in a bundle onto a metal hook. Footwear was lined up on the floor, but I no longer had the pair of boots that I had to exchange earlier during the death march. Now most of us had a pair of canvas shoes with wooden soles. The canvas top was nailed to the sole, and since the stiff wood could not bend, eventually the canvas separated at the heel and often fell totally apart from the stress of walking. So, for a while I had to walk barefoot until later when I received a replacement.

Our bundles of clothing were hung up in rows in a hot room where the temperature was raised to exterminate lice. While that was being done, we walked into the large shower room where pipes hung across the ceiling with numerous showerheads attached. We all showered simultaneously in a fairly warm water stream and occasionally got a small cube of gel type soap. When done, we drip dried. We received a clean set of underwear, but before putting them on we had to search all the seams for lice and eggs. If we found any, we squished them with our two thumbnails, and they popped.

The undergarments were not of a soft quality. They were made of a cotton bedsheet material. You pulled the long sleeved undershirt over your head, and it had an opening at the neck and one at the ends of the sleeves that you would tie closed. There weren’t any buttons. The underpants were the length of longjohns and also had a slit at the calf with laces to tie.

I was fortunate enough that lice never took a liking to me, so I never needed an in-between delousing and never picked lice up from anyone else either. Also during this process our heads were shorn to the skin. Those who had a lot of body hair had to be clean-shaven over those areas. In addition, everyone’s pubic hair had to be shaved off.

Once all of this was completed, you then put on a clean uniform. You never got the same one back that you came in with.

A 19-Hour Workday

The next work assignment was going back to the same forest area that we had been working in before. Now we were paired in two-man teams. Using a pick and shovel, we had to dig straight down to a depth of about four feet where there was a horizontal layer of granite-like stone. It was about two to three feet thick and with the pick, fist-hammer, and flat stone chisel we had to break the layers apart, then excavate the loosened slabs to ground level.

We constantly strained to achieve our daily production quota or “norm” to earn 500 grams of bread but could never reach that goal. When a team came close to it, the daily norm was immediately raised to an unreachable level. Our long workdays were up to 19 hours.

We often talked among ourselves. Some men had heard rumors that there possibly had been some sort of agreement among nations establishing prisoner rights. If that was the case, we certainly had no such rights. The Quakers from America had been sending vast amounts of gift food to prisoners all around the world. I know this for a fact because I saw the empty cartons and read the printing in English. I could interpret it, having learned that language at school. We never got any of the food, yet those cartons were lying empty on the garbage piles. The Russians used those shipments for themselves or sold the food on the black market. I also saw large empty wooden barrels of curded butterfat that were also labeled as given by the Quakers.

It was about that time that I was approached by some of the prisoners who were smokers. They had noticed me reading my Bible and wanted me to part with a few pages from it for rolling. At first, I was reluctant and did not think that would be a good thing to do. I gave it a lot of thought because I cherished my Bible and prayed about that as well. But driven by hunger, I finally gave in. Slowly, I sacrificed a page or two from the Old Testament part of my Bible. I prayed for forgiveness to God as I watched page after page from my Bible actually go up in holy smoke. I was so happy to get extra nourishment in return. Now I was running a trade business and playing a game to stay alive.

German prisoners work outside the boundaries of their camp in the Soviet Union. Gottfried Dulias chopped wood and carried logs in similar fashion to these men.

We estimated that in the Penza region of Russia alone there were at least 25 separately operated gulags. Each one originally held up to 5,000 prisoners. That gives one some idea as to how many men the Russians actually had to feed. We discussed the various facts we knew or heard from others regarding these numbers. When a prisoner was transferred from a hospital back to a camp it was not necessarily to the same one he came from. So we were able to find out more about what was really going on in the other camps and places.

A few prisoners who were transferred to our site came from the Moscow area. They were sharing information with us about where they had been and what went on there. Around Moscow the Russians had set up so-called “parade camps” for inspection purposes by dignitaries or foreign reporters so the rest of the world would know how well the prisoners in Russia were treated. In those camps the POWs were served better food and received better care and treatment.

Another “task” of ours was working in a stone quarry or processing plant. Earlier I mentioned that we had dug up layers of granite stone in the area where we felled the trees and also made the hand-hewn beams for the reinforcement along the Volga River bank. Following that, we had to load those harvested stone slabs onto trucks to be transported to that plant. The trucks were all American Studebakers, given to the Russians through the Lend Lease agreement with the Americans. The help they received with that agreement was a tremendous military advantage for the Russians. The equipment enabled the Russians to gain time to replace the losses the Germans had inflicted on them.

After they were transported to the processing plant, the slabs were unloaded to form huge piles. A stone-crushing machine that produced gravel to be used as roadbeds was located there. But the machine could accommodate stones no larger than the size of a man’s fist. So, our job was to knock those slabs into smaller pieces and then load them onto rail carts that could be tipped and unloaded into a pit at a lower level.

First Postcards Home

Late in 1946 we were allowed to write our first postcards home. We were supposed to receive and send one per month, but often a month was skipped. We could only write 25 words or less, we were told, or else it would never make it home. Those postcards were pre-printed double cards with the sending and return address. One side of it was blank to write to our family, and the other was identical as a return card for our loved ones to use in reply, also with only 25 words. We didn’t have a pen or ink and only the rare pencil that one or the other had made the rounds among us.

Once again I had one of my brilliant ideas! Why not make my own ink and writing stick? From the workshop at our camp I obtained some iron file dust and mixed it in a spare tin cup with the juice from gall apples, which were ball-like growths that could be found under numerous oak leaves. The grown oak trees around our camp produced quite a good number of these, and I had no trouble finding green and juicy ones suitable for my new project. The acid juice mixed with the iron file dust resulted in genuine, nearly black ink. It did not even smudge after the writing dried if it had accidentally become wet from spilled water. I used a dried oak twig with a carved point as my writing stick for my first card home. I still have it today.

At a later time I traded a page or two from my Bible and some of my ink to a metal worker for a penholder and pen that he had made at the camp workshop. Since I was making a good amount of ink, I managed to trade some of my supply to fellow prisoners for some of the usual foods and so saved my Bible pages for later trades.

At the tool shop there was a foot-operated grindstone stand. The rotating stone wheel was half submerged in an attached trough, creating a whetstone effect for sharpening our tools. Some of them were spades, shovels, picks, and yes, even knives as well as cold chisels that we used to separate layers of granite stones in our quarry holes, as well as pick points that needed sharpening. Our hatchets and axes got sharpened as well.

On Mondays, the workday routine started all over again. The only reprieve we got was when there was an extremely heavy and steady downpour of rain, which we welcomed. Then we could stay in the camp, although we had to deal with the mud plopping down from the ceiling of our underground barracks. At each end of our bunkhouse where steps led down to the floor level of our living quarters, the rain collected when the gullies at the bottom were overflowing. We had to bail the water out.

We did get lunch on those rainy days and were not as exhausted as on those hot sunny days when sweat soaked our clothes during long hours of hard labor. During our march in the evening back to camp, the cooled air did dry our shirts and pants, so we did not take them off before going to sleep.

Injuries in the Gulag

I remember one hot day, while laying asphalt on the new road that we were building, one of our fellow prisoners became seriously injured. For the two layers of asphalt of the road building we had a spreading machine. It distributed the asphalt evenly over the entire width of the road and rolled on rails, temporarily placed at both sides of the road. At the front of it was a long open trough in which a rotating worm-screw type of gear was located. It moved the hot asphalt from the center toward the sides of the trough, evenly distributing it. The worm gear was so constructed that one half of it spun to the left and the other half to the right, while the single jointed axle turned in just one direction.

Dulias (left) and two of his fellow cadets are dressed in summer flight uniforms.

Studebaker dump trucks brought the asphalt and dropped the mixture slowly into the center of the trough. Thus, the machine spread it evenly over the entire width of the road because at the bottom of the trough was an open slot that by hand control widened and closed depending on what thickness the layer had to be. The machine rolled slowly forward on its rails as the asphalt was laid down in a controlled thickness. Before each truck dumped a new load into the machine, two men had to shovel and scrape some misplaced asphalt back into the trough. I was one of the two men assigned to do that job this particular day.

My partner collapsed and fell rear end first into the rotating worm gear. The machine operator stopped the gear in an instant. But unfortunately not before he could prevent the sharp worm gear from cutting deep into the poor victim’s left buttock. It was almost severed from his body. It also tore his hipbone bare. This was an extremely gruesome sight! Not much blood came out of the wound, but the terrible sight of the reddened flesh and the exposed bone was sickening. We lifted the unconscious victim onto an empty asphalt truck that brought him to the prison hospital in Grüntal (Greenvale).

As a result of all the hard, physical labor, I developed a hernia in my lower abdomen. It was the size of half an egg, and it had popped out from my lower right groin. Building a road between Moscow and Stalingrad, lifting and placing heavy iron rails for the asphalt spreader, had taken its toll on me. We just had to accept and deal with those unpleasant realities in our own personal way. What a life we had.

A Series of Mini-Journals

Creating little notebooks gave me inspiration, and I started to record some information about myself in a series of mini-journals and in the form of letters to my family. It is important to remember that at the camp anything in writing with the exception of Bibles and prayer books if found would be confiscated. I managed to hide all well. Some time in the hospital also gave me the opportunity to acquire little stacks of Russian cigarette paper for rolling machorka. Since I already had enough paper for my booklets I traded my portions for more food supplements. I was writing my journals in hopes of being able to eventually send my work back home with one of the prisoners who would be lucky enough to be released with the occasional transports.

Dulias poses in front of a two-seater Olimpia Kranich soaring plane after a solo flight in the summer of 1944.

I wrote to my family that I had a fever and compared myself to some starving soul from the poorer caste in India. My recovery in the hospital was not the greatest, but I could slowly gain some weight back. In addition to malnourishment and dystrophy, I got sick from some type of malaria, but it was not the familiar tropical kind. In fact, once you got over it you were not immune from getting it again. Unlike the tropical type that stayed with you, this non-tropical one occurred only by another bite from some kind of insect. This type of malaria caused a high fever that could be fatal. I contracted that three times and got over it, thankfully. But as was later discovered, my heart was affected and enlarged, and that caused it to develop an irregular heartbeat.

By February 1946, I had the opportunity to give my first journal to a fellow prisoner who was a Czech. He was supposed to be on the first transport home, and so I asked him to keep it, hide it, and when he reached the homeland to please send the little journal to my parents. I wrote their address on it for him. I sent two other journal booklets with released POWs returning home, but only this first one made it through, and my parents saved it for me. I still have it today.

The Journals of Gottfried P. Dulias

The following, for the first time in more than 60 years, is what I am reading and translating today. It is very painful for me to reminisce over these sad but true facts, but at the same time I am finally able to share my story and release what I had hidden, even from myself, for too long. In the cigarette paper booklet, I withheld from my parents the more unpleasant happenings.

“My Dear Ones,

“Paper is scarce, as is the case with everything else here. Up to now writing to you was impossible. I want to give you a small review about my past here. In March of 1945 I became a POW at Naggi Sallo in Hungary at the River Gran, not far from Budapest. We marched many kilometers until we were loaded into railroad cattle cars. At Jasbereni (Hungary) there were wider railroad tracks for our transport to Russia. Once in Russia we had to pass through numerous temporary campsites and were interrogated and everything we had was confiscated. The train made many stops and we were de-loused and so on. By May 9th we arrived in Grüntal, near Kasan (Kazan) at the Volga River, west of Moscow. There we worked on the “Kolkhoz.” It was hard work for sometimes 16 to 19 hours with very little food. Many of us became sick, many died. In October 1945 there was a rumor that the zone behind the Volga had to be cleared of all POWs and the sick were put into the Lazarett (camp hospital) and the others were dispatched to a camp in the vicinity of Pensa. I counted myself as one of the lucky ones and was admitted to the Hospital….”

I continued writing and telling my parents that I had a job at the hospital doing errands, such as picking up potatoes and helping the medics to take care of the other sick and wounded comrades. I guess I was something like an orderly. I was also told that I had to stay until the last prisoners would be transported home and that it would not be in that same year. I continued writing in that first journal:

“You will be astounded about what I will personally reveal to you later when we are together again. My future is all set. I am very anxious to see how my sisters look [my two younger sisters would be 19 and 17]. I don’t have my photos anymore because they took everything away from us. Only in my dreams can I see all of you. Soon I’ll be making it to my 21st year of life and I’ll be of legal adult age. Can you imagine that? How fast time goes by? Hopefully things are not too rough by you? For all the time that I have been away from you, it can be made up, well, mostly in reference to the food. I am also curious about what happened to my dear friend Irmi. I’m sure that she stopped at the house to inquire about me. Please convey my ‘heartfelt greetings’ to her and tell her that soon I will be home. Here in the hospital and so far throughout my stay, I was together with a comrade who is also from Fürstenfeldbruck. His name is Hans Weber. Please contact and let his wife know that he is still alive and surely will come home soon. If he comes home first, he will visit you and tell you about me. Once we are both home then, that day will be celebrated every year as a ‘New Birthday’ and that will be the right thing to do. So now I close for today, and, God willing, we will see each other soon, healthier and happier. My ‘heartfelt greetings and kisses’ to all of you, and my friends, relatives and acquaintances, Gottfried.”

In March, Hans was fully recuperated and was sent back to the camp.

On July 2, 1946, I continued writing.

“My Dear Ones,

“It turned out differently than we had expected. Until now, no more transports left here. But now in July there are supposed to be some more returning home. Sorry to say that I got notified that I was to be dispatched back to the camp. It seems they need more men to finish the new road between Stalingrad and Moscow. They wanted to have it completed by October. Everyone who was capable of working was required to go on this project. Therefore, that’s how we became involved. All the patients from here are supposed to be sent home within a short time, but those of us left behind have to get stuck with it once again. So we are being promised that by the winter we will be sent home. Let’s hope so! It looks like tomorrow we will be sent to the camp. Therefore, I am writing these few lines quickly and will leave this letter behind as well as two more. Whoever is able to get on the transport back will dispatch these letters to you in hopes that you will receive at least one.”

There were rumors and more rumors and one disappointment after the other.

Actually, the German chaplain at the hospital had been a wonderful man and most inspiring. We were able to spend quality time together in discussions as well as with prayers. My friendship with him strengthened my spirituality. Actually he helped me in finding the fellow patients and prisoners who would be going home so that they could carry my messages with them.

I lived with the positive hope and outlook that not only my parents would know that I was indeed still alive, but also the fact that one day soon I would rejoin them.

About that same time in camp we were issued our first postcard, which was given to us by the Red Cross. Finally, we were given permission to write one card home. The card had a return portion on it with our address. I decided that I would hold on to the postcard until a later date because I had no idea what my new location would be and if I was moved from one place to another, they would not forward it. Instead, I stuck to my original plan of sending my own messages home along with men who would be released soon.

My journal continues:

“I heard that the new camp where I am supposed to go is much better managed than the one I was in earlier. Some of our patients came from there and told me that they got more to eat than at the hospital.

“All I can say is, who knows why it’s good that I am being sent back to the prison camp? The good Lord will lead me the right way and not forsake me. Someday He will lead me on the road home. So let us not lose our faith and courage and let’s keep hope for finding freedom.

“Greetings and Kisses, Your Gottfried.”

Additional thought: “By the way, I am here with the former top Pastry Chef/Baker Herr Maschinski, now called ‘Maschner.’ He is from Osterode and had his business across the street from the Catholic Church. He was there to the last days and reported that Osterode was surrendered to the Russians without a battle and that it seemed that most of the city appeared undamaged.”

On July 8, I continued writing:

“My Dear Ones, until now we did not yet leave the hospital. It looks like it will not happen because the doctor said that now in July the transports leaving here are leaving directly for the homeland. If there are not enough passengers then maybe we would have the possibility of being one of the ‘lucky ones’ to be part of it. Here anything can happen! The Russians are in every way ‘unpredictable.’ Therefore, let’s hope for the best. If I should not be one of those lucky ones, we have to console ourselves with God’s word. The good Lord has so intended and He knows when it is time for me to be sent home. I remain in God’s hands; He will lead me and guide me when it will be best. The Bible verse at my Confirmation is again and again my consolation. ‘Do not be afraid, because I freed you, fear not, because I redeemed you. I called you by your name, you are mine. I belong to Him and He is in me and beside me, what should I be afraid of? The Lord is my Shepherd I shall not want.’ Better to go through God’s school than be forsaken by Him….”

I continued writing by telling my parents that these nice scriptures I remembered were embroidered and hung framed on the wall over the sewing machine in our home. “I am clinging to these scriptures and again and again they comfort me. Therefore, the good Lord already knows when it’s my time to be sent home and He will lead me to you, now we just have to patiently wait.”

So, I continued writing in my journal, sharing whatever I could day by day, week by week.

Finally, on January 4, 1948, Gottfried Dulias was released from Soviet prison weighing 70.5 lbs. He was repatriated to West Germany through the American occupation zone. Although he endured great hardship, Dulias was indeed among the fortunate. Hundreds and hundreds of thousands of German prisoners of war were marched into Soviet captivity and never returned. Dulias was a frequent guest and exhibitor at historical enactments and other events.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 15th, 2021

November 15th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: