The Baltimore housing projects where 25-year old Freddie Gray tried to outrun police before he was detained, dragged into the back of a police van, and later died as a result of a severed spine, are spacious and clean but there are no yards. Manicured hedges line the Gilmor Homes development. Low-rise buildings ring a basketball court where dozens of children played with newly installed rope nets.

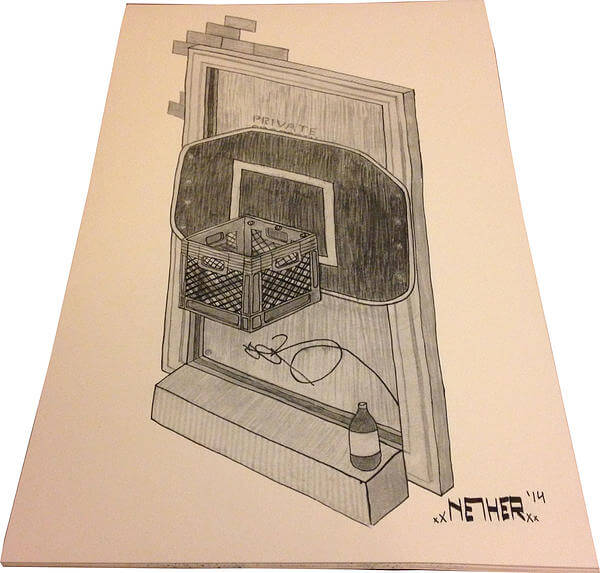

Eddie Conway, a former Black Panther turned producer for the Real News Network who spent 45 years in prison, paid for nets. Before Conway, Gilmor’s residents shot basketballs into milk crates fastened to a plywood backboard. Needless to say, Conway is now a local hero, along with a street artist named Nether who painted three murals on Gilmor’s exterior walls. These massive two-story paintings have become local tourist stops and mourning sites. In front of one of them sat a pair of black boots still in the box. Nether said they were a gift for Gray purchased before his death.

Having covered two wars, and nearly three years of reporting from the occupied Palestinian territory and Israel, I decided to visit the Baltimore projects last week in the wake of the National Guard’s deployment. Although it bears little resemblance to the Middle Eastern conflicts I have seen, the televised images of the National Guard and tear gas, and public art works on walls that captures politics and death drew a superficial parallel I wanted to investigate further.

Gray is deeply missed amongst Gilmor’s tight-knit community. It’s the kind of place where everyone knows everyone. Gray was popular and had boyish good looks. He was known to spend his spare time outside, playing music on his phone and dancing with his closest friend and brother-in-law Juan, 27, a carpenter who makes jewelry boxes who asked me not to publish his last name. The two were inseparable over recent years. Juan smirked as he thought back to Gray’s dance moves.

“He was my best friend. That’s the person I’ve been through everything in my life with,” Juan said. When Juan was 14 a stray bullet killed his paraplegic mother meters from where Gray was arrested. When it happened, Gray was there for him.

Gray died on April 19, 2015, and before long sections of Baltimore were on fire and there was unrest till charges for homicide and wrongful imprisonment were filed against six Baltimore city police officers. The National Guard was called in to patrol, mostly in the area where Gray was arrested, Sandtown-Winchester, or “Sandtown” as those who live there call it. Tensions escalated after the Bloods and the Crips penned a unity letter against police and Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake described the demonstrators as “thugs,” prompting outcry from residents and other city officials who said her remark was derogatory.

While Baltimore is no longer at a fever pitch, locals are still angry with police over the handling of riots. Public schools were closed, shops were boarded up, and a cement barrier guarded by officers was erected, which locked in Sandtown’s residents under the pretense of preventing the riots from spreading. After dark, plumes of tear gas fired by police wafted into homes. Countless people in Sandtown told me those days felt like a “military occupation.”

“In other countries we see it all of the time. Like this is another regular day in like Greece, or wherever, in Brazil,” said an activist with Baltimore Bloc, an organization that advocates for victims’ families.

“Driving through West Baltimore with the National Guard patrolling the streets just felt so surreal,” Gracie Greenberg, 25, who volunteered as jail support for arrested protesters, said. She violated curfew in order to get those who had been released at night home safe. “It looked like an occupied war zone,” Greenberg said, “what I would imagine one to look like.”

Moreover, those closest to Gray are still grieving. “I have nightmares,” said Kiona Craddock, 25, a neighbor of Gray’s grandmother who filmed the arrest on her phone. She remembers Gray looking at her straight in the eyes and said, “I can’t breathe,” while police stood over him.

Mural painted by Nether at the site where Freddie Gray was arrested, Gilmor Homes, Baltimore. (Photo: Allison Deger)

Joe Giordano, 41, a Baltimore native and photojournalist for City Paper, met me at a Soul Food restaurant near where Gray was arrested. He covered all of the protests and was one of two journalists detained without charge. Giordano said during the first clash authorities held back for 40 minutes while youth from Sandtown ignited their neighborhood. “They locked it down after the police car was destroyed, after the check-cashing store was destroyed, after the CVS was destroyed, after two MTA [Maryland Transit Administration] vehicles were burned,” he said. “I really don’t get it. It’s one of the things that sticks out in my mind. I don’t understand why they waited so long.”

By the time I arrived, the guard had left and the general curfew was lifted. Incidentally, the city has a year-round curfew for youth 14 years and under, a controversial law enacted last year under which minors can be brought to detention centers if found on the street after 9 pm.

Signs of the confrontations and looting after Gray’s death were in plain sight. Sandtown is a food desert and the only market where fresh vegetables are carried is now charred. Vacant and dilapidated buildings line the main streets. Many of the spaces were burned out during the 1968 riots and never rebuilt. Others were boarded up two weeks ago as protection from the recent riots.

Looking forward, Juan hopes the six officers involved with Gray’s death will serve time in prison. When the State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby announced that they would be prosecuted for homicide and wrongful imprisonment, it was a surprise to many. But for Gray’s friends and family she was fulfilling an election promise.

Mosby took her post last January when she beat incumbent Gregg Bernstein, who was in office during an uptick of murders in Baltimore. Mosby campaigned hard, and community members who are now protesting for Gray organized at least 60 protests against him. While Bernstein was perceived as soft on cops who kill and on gang violence, Mosby emerged as an advocate for victims’ families. Her cousin was killed outside her front door in a shooting when she was just 14.

While popularly supported–“We think we have Mosby on our side,” Juan said–she now faces challenges. Baltimore’s police unions have called for her removal from the case. They say her marriage to Nick Mosby, a Baltimore councilman, is a “conflict of interest.”

Juan’s message to Mosby: “don’t let them intimidate you.”

Murder—specifically the murder of unarmed black men by police—is a serious and unfortunately prevalent issue facing Maryland. While violent crime was subsiding in the rest of the country, the ACLU reported last March that between 2010 and 2014, 109 people in the state died in encounters with police. Nearly 70% percent of the victims were black. Of those, 40% were unarmed. “The number of unarmed Blacks who died (36 people) exceeded the total number of all Whites who died (30 people), armed or not,” wrote the ACLU.

Alarmingly only 2% of the 109 killed were charged with any crime, meaning encounters with police in Baltimore can be dangerous if not deadly, even when the person being detained has committed no crime. Residents know this in emotion, if not in hard statistics. Locals in Sandtown referenced the ACLU report to me. Juan told me last year he was arrested and roughed up by police only to be released without charges.

Moreover in the 1970s, Maryland passed what is known as the “Law Officers Bill of Rights,” legal protections where police are given ten days before they have to answer to detectives. That means if Juan were killed by an officer, the officer would walk from the scene. But if Juan were to do the same, he would go straight to jail. For Sandtown residents this shows there are two sets of laws that govern their world, one for the police, and one for them. Although there are groups working to change this policy, reform was shot down in the Maryland legislature one month before Gray died.

Sandtown is a community grappling with mistrust of the system to bring a guilty verdict. While residents were certainly unhappy with having federal marshals on the streets, their focus was not on the clashes and curfews, but on the trial.

Kolson and nearly everyone I spoke with treated these issues as local Baltimore issues. Ferguson, Oakland and other U.S. cities where killings of unarmed black men have prompted a national conversation about race and policing were not on the tips of the tongues of Baltimoreans. They see these same relations, but on a micro scale.

What struck me most was the hopefulness of the community. When I have covered similar sorts of deaths in the West Bank, there is no expectation that a Palestinian can win in court against an Israeli soldier. Conversely in Baltimore residents believe if they concert their efforts and keep protesting through the upcoming trial for the officers who dragged Gray into the back of the police van, there is a sliver of a chance guilty verdicts will follow.

As I left Sandtown, Juan insisted on a closing point: “racism is not among the people, racism is among the laws that are created by the people—I definitely learned that.” His opinion of law enforcement is mixed. He has interacted with good and bad cops. But as he sees it, there is no accountability for the officers who do kill unarmed civilians, specifically black men. And that lack of accountability when translated in practice in Gilmor Homes means Juan, his friends, and his relatives walk around feeling at risk.

“If we don’t unite and stay strong there are people out there just waiting to take us from our families,” Juan said.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2015/05/letter-from-baltimore

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 21st, 2015

May 21st, 2015  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: