As one of the most heavily trafficked inland waterways in the world, Lake Erie has seen more than its share of catastrophe and tragedy. While it is the second smallest of the five Great Lakes, an enormous number of ships have sunk beneath its waters, possibly as many as 2,500 according to the estimates of some archaeologists and historians.

So far, only 277 of these wrecked vessels have been found and identified. But new discoveries are being added to that list all the time, as underwater explorers launch air- and water-born searches from both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border.

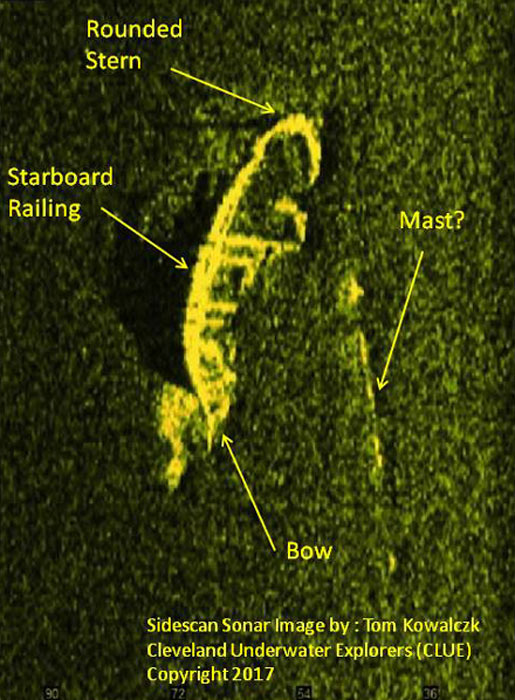

The oldest Lake Erie shipwreck is the Lake Serpent schooner which was discovered by the Cleveland Underwater Explorers in 2015. ( Cleveland Underwater Explorers )

Shipwrecks Galore in a Small Inland Sea

Lake Erie first emerged as an important transportation route in North America in the 18th century. The lake covers an area ranging from western New York to northern Ohio and southern Michigan, which meant it offered rapid inland access to traders and explorers from America’s original 13 colonies and states.

There were likely many boats and ships that sunk in Lake Erie in the 17th and 18th centuries. But most of those vessels were quite small, which would make them difficult for modern underwater divers to find. As a result, exploration and recovery activities have focused on ships that sunk to the bottom of Lake Erie in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Perhaps the most notable shipwreck recovery on Lake Erie is one that occurred just six years ago. That’s when the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo, Ohio, announced that a ship lost on Lake Erie 186 years earlier had finally been found.

In September 1829, a 47-foot-long (14-meter-long) vessel called the Lake Serpent left Cleveland bound for Cunningham’s Island, 55 miles (88 kilometers) away. After filling the ship’s hold with limestone boulders, they set out on a return voyage to Cleveland. But caught in an unexpected tempest, the ship sunk somewhere on the way home, never to be seen or heard from again.

Or at least until 2015. Everything changed when Tom Kowalczk, a remote sensing specialist from the archaeological group Cleveland Underwater Explorers (CLUE), spotted something unusual while scanning an area of the lake bottom near Kelleys Island (the current name for Cunningham’s Island). When CLUE divers investigated they found the remains of a small wooden schooner, which was clearly quite aged.

The divers found two pieces of evidence that identified the ship as the Lake Serpent . First, they discovered an intricate carving of a snake on the vessel’s bow , matching what the historical records said the Lake Serpent featured. Second, they found several limestone boulders still lying in the ship’s hold, of the type that were still being quarried from the Lake Erie islands in the late 1820s (limestone was harvested in block form starting in the 1830s).

The Lake Serpent schooner, Lake Erie’s oldest shipwreck, would have looked this ship. ( Historical Collections Of The Great Lakes At Bowling Green State University )

As of now, the Lake Serpent is the oldest shipwreck recovered from Lake Erie. It is not, however, the only 19th-century limestone-carrying vessel to be found on the lake bottom near Kelleys Island.

In 2018, the National Museum of the Great Lakes announced that divers had discovered the remains of the Margaret Olwill , a 554-foot (169-meter) ship that had been sunk by a vicious storm in 1899. Its hold had also been filled with limestone quarried from Kelleys Island when Lake Erie’s unpredictable weather brought about its demise.

Another hotspot for underwater archaeologists exploring Lake Erie is the Manitou Passage . This semi-treacherous stretch of water lies close to the shore of Traverse City, Michigan. In the 19th century, it claimed the lives of many men and many ships carrying lumber from one port to another.

Here, the clear water makes it easy to spot several of these shipwrecks from above. That includes the scuttled remains of the James McBride , a 121-foot (37-meter) vessel that was lost during a wicked storm in 1857.

It must be emphasized that this is just a small sampling of the shipwrecks that have been found in Lake Erie. The gigantic Great Lakes , which feature tides, weather, and waves similar to those produced in the planet’s oceans, are synonymous with shipwrecks. But even among its companions, Lake Erie stands out.

“We think Lake Erie has a greater density of shipwrecks than virtually anywhere else in the world—even the Bermuda triangle,” said CLUE co-founder Kevin Magee, an engineer at NASA’s Glenn Research Center, in the NASA publication Earth Observatory .

The Battle of Lake Erie in 1813, painted by William Henry Powell in 1865, shows Oliver Hazard Perry transferring from the Lawrence to the Niagara. (William Henry Powell / Public domain)

Lake Erie and its Role in the Settlement of North America

Lake Erie, which was named after the first Native American people encountered by European explorers in the 17th century, was settled on opposite sides by the Americans and the British (the original British Canadians).

It was actually the last of the Great Lakes to be explored and used as a transportation corridor, mainly because of resistance from the mighty Native American Iroquois Confederacy to European activities in the region. That resistance melted away over time, as the Iroquois population was decimated as a result of their contacts with European nations and settlers.

The lake was the site of heavy warfare during the War of 1812, which was fought between the newly independent United States and the British Empire. At least some of the shipwrecks that currently litter the lake’s bottom may have been vessels that were sunk during this fierce conflict, although so far none of these ships has ever been recovered.

In the post-war era, relations between the Americans and British Canadians warmed considerably, and Lake Erie was safely traversed by ships from both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border from that point on.

Growing urbanization along the lake’s borders caused a dramatic increase in maritime trading and fishing activities in the 19th century, which unsurprisingly led to a huge rise in the number of reported shipwrecks. This was long before weather forecasting technologies had been developed, and before wireless broadcasting allowed land-based observers to issue warnings to ships that might be in peril. Consequently, many ships were wrecked by massive waves generated by sudden storms during the 19th century on all the Great Lakes, with Lake Erie likely suffering the highest casualty rate.

The shipwreck of the James McBride, a 121-foot-long (37-meter-long) brig that was lost in a storm in 1857. (Mitch Brown / U.S. Coast Guard Air Station Traverse City )

The Challenges of Underwater Archaeology in Lake Erie

While 80 percent or more of the ships believed to occupy spots in Lake Erie’s underwater graveyard have yet to be discovered, archaeologists know many (maybe most) will never be found.

In general, wrecks in Lake Erie remain close to the surface since the lake itself is relatively shallow. This is a classic example of the two-edged sword: while it makes wrecks easier to spot from the surface or the air, it also exposes sunken ships to more powerful erosive forces, such as stronger currents and warmer waters.

“The shallower the water, the less likely it’s found [in the same condition as when] it sank,” Chris Gillcrist, the Director of the National Museum of the Great Lakes, told Smithsonian Magazine . “There are shipwrecks found off Kelleys Island in 15 feet of water and they’re pancakes.”

At a depth of 205 feet, the Sir CT Van Straubenzie has the distinction of being the most deeply sunken vessel ever found on the lake’s bottom. The ship collided with a steamer on September 27, 1909, approximately eight miles (13 kilometers) east of Long Point, Ontario, and quickly disappeared far beneath the lake’s surface. Despite its great depth underwater divers did eventually locate the ship, and while they found it covered with barnacles overall it was in quite excellent condition.

In a case like this, exposure to erosive forces is minimal and the conditions for preservation ideal.

“One of the remarkable things about Lake Erie and Great Lakes [deeper] shipwrecks is how well they are preserved due to the cold, fresh water,” Kevin Magee explained. “Wrecks in saltwater start corroding immediately. In the Great Lakes, you can find old wooden ships that are hundreds of years old that look like they just sank.”

Efforts to unlock the secrets of the Lake Erie graveyard will likely continue indefinitely, as underwater archaeologists further explore the depths of a body of water with a long and often tragic history.

Top image: Lake Erie is believed to be home to over 2,500 shipwrecks. A few have been found washed up on beaches after violent storms. Source: David Arment / Adobe Stock

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 1st, 2021

November 1st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: