In his seminal work entitled Anglo-Saxon England published in 1943, Sir Frank Stenton states that “the overthrow of Penda meant the end of militant heathenism and the development of civilization in England.” Historians of the 20th century were mostly content to dismiss Penda’s reign as unimportant, or to give him no more than a cursory mention as a pagan warlord who was a scourge on the Christian kings of 7th-century England. In recent years however, historians have taken a second look at Penda of Mercia and questioned the long-standing negative view of his reign.

It was Penda’s 30-year rule of the kingdom of Mercia that set the foundation for the success of later Christian kings such as Wulfhere, Æthelred and Offa, and it was Penda who made Mercia powerful enough to earn its place among the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy. So how did Penda end up on the wrong side of history, and why should the story of the last heathen king of Mercia be rewritten? A closer look at the historical sources reveals there is more to Penda than previously believed.

Penda of Mercia was the last Mercian king to die a non-Christian, while most Anglo-Saxon kings converted to Christianity. The image shows Æthelberht, who was King of Kent from 589 to 616 AD, being baptized by Augustine of Canterbury. ( Public domain )

Rex Perfidus , the Traitorous King Penda of Mercia

Penda, son of Pybba and descended from the noble house of Icling, ruled the kingdom of Mercia from approximately 626 AD until his death at the battle of Winwæd in 655, when his army was defeated by the Northumbrians led by King Oswiu. Penda was the last Mercian king to die a non-Christian, and at the time of his reign, was one of the few remaining Anglo-Saxon kings to resist converting to Christianity. It was his determination to remain religiously neutral which seems to have been the root of Penda’s negative reputation as rex perfidus , or the traitorous king.

There are very few records of Penda’s reign that survive to this day. The main source of information about his life is Bede’s History of the English Church and People , which is the closest chronologically to Penda’s actual life. Parts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Tribal Hidage, as well as the Historia Brittonum , offer some clues, but some of these sources were written as late as centuries after Penda’s death. The most detailed account comes from Bede’s work, and it is also likely where Penda’s career on the wrong side of history began.

Bede tells the story of the conversion of the English people, who were, in his mind, the chosen people of God, and the foundation of the English Church. Penda did not fit neatly into Bede’s vision of disparate kingdoms united by faith, and so Bede painted him as an impediment to the divinely-ordained process of Christianization, an evil pagan warlord who slew Christian kings in his quest for military domination. Penda was in fact highly successful in his military campaigns and as a result became the dominant ruler in southern Britain in the 640s and 650s AD, but Bede largely glosses over this fact and reduces Penda and his people to nothing more than “idolaters and ignorant of the name of Christ.”

Map of Anglo-Saxon England during the time of Penda of Mercia. (Hel-hama / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Forging Penda’s Mercian Empire

While Bede chose to represent Penda’s militarism in a negative light, military victory was critical to Penda’s rule and in creating his empire of kingdoms under Mercian rule. Mercia was not one of the most powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the late-6th and early-7th centuries, it was still expanding and consolidating itself, and some of its territories remained hotly contended by neighboring kingdoms. These neighboring kingdoms were all either converted to Christianity or in the process of converting by the time Penda came to power, and so Mercia stood out among them as an island of heathenism.

Warfare was not a tactic unique to Penda’s rule. Anglo-Saxon kings (and British kings before them) often used war as a way to enrich themselves with plunder and gain power over those they defeated. Increasing the power and wealth of their kingdom also allowed kings to bring more warriors to their court with lavish gifts, and to earn the fealty of tributary kings from less powerful kingdoms. Penda’s many victories on the battlefield were undoubtedly a key part of what drew many of his allies to his court. They also helped raise Mercia’s status among the Midlands kingdoms until it had become one of the most powerful kingdoms in Britain by 655. Penda, as its over-king, held imperium over most of central Britain.

Bede describes how Penda marched into battle at Winwæd with “thirty legions of soldiers experienced in war and commanded by the most famous ealdormen,” these “ealdormen” being his under-kings who accepted Penda as their ruler. The kingdoms that were tributary to Mercia in 655 covered a very large area that included Middle Anglia, Hwicce, East Anglia, Deira to the North, and the British kingdom of Gwynedd to the West.

Penda’s empire has been compared to the “religious imperialism” used by other contemporary Anglo-Saxon kings to consolidate their power. The suggestion is that Penda was adapting to a changing political landscape by escalating his use of aggressive militarism to compensate for the lack of ready-made power structures that came from converting to Christianity. Nicholas Higham, a prominent historian of the period, theorized that Penda’s model of rule was based on pagan “sacral” kingship which led him to reject Christianity as “a cult designed to enforce subordination.” However, the picture painted by the historical sources is not so clear and Penda’s motives for refusing to convert to Christianity appear to be more complicated.

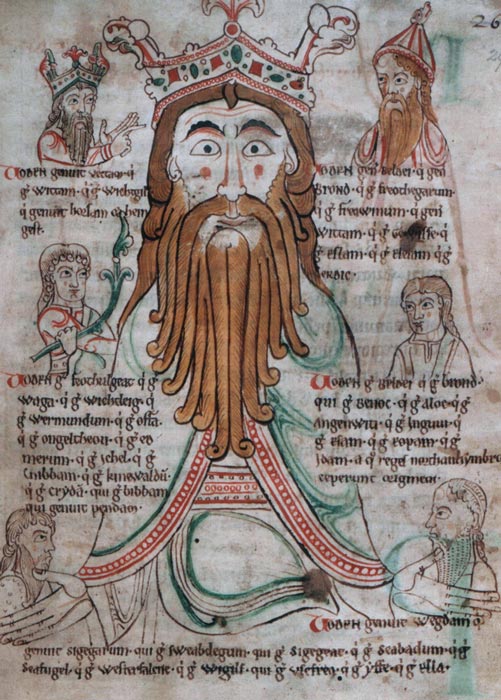

Anglo-Saxon kings were linked to the divine through personal kingship with the god Woden. The image shows Odin & Sons from the 12th-century Libellus de primo Saxonum uel Normannorum adventu. ( Public domain )

Sacral Kingship and State Religion

There is little enough evidence of Anglo-Saxon practices to determine for certain what model of kingship they followed, but the “sacral kingship” theory is the favorite among scholars of the era. The idea of sacral kingship was that the king’s primary role was to preserve the people through his relationship with the gods as a living link to the divine. He would do so by acting as both head of state and as a sort of head priest, enacting rituals and giving divine guidance to his people.

The king’s link to the divine was inherent in his role as monarch, but many kings also claimed personal descent from divine sources. For Germanic kings such as the early Anglo-Saxons, this would mainly be done through written genealogies that detailed the ancestry of the royal family line from the god Woden. Penda was one such king – in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles , Penda’s personal genealogy traces his ancestry directly to the god Woden:

“Penda was Pybba’s offspring, Pybba was Cryda’s offspring, Cryda Cynewald’s offspring, Cynewald Cnebba’s offspring, Cnebba Icel’s offspring, Icel Eomer’s offspring, Eomer Angeltheow’s offspring, Angeltheow Offa’s offspring, Offa Wermund’s offspring, Wermund Wihtlaeg’s offspring, Wihtlaeg Woden’s offspring.”

This divine ancestry was believed to endow kings with divine wisdom and supernatural power, but an individual who aspired to rule would not be handed the crown on the basis of ancestry alone. Not all descendants of the gods were thought to inherit their divinity, and a king must first prove himself to possess divine power and wisdom before he could be made king – usually through military successes, or perhaps by demonstrating an ability for prophecy or healing. In Penda’s case, his many military successes throughout his reign would have confirmed to those under his rule that he was indeed descended from the god Woden, and was an earthly embodiment of the war-god’s divine power.

The idea of sacral kingship persisted throughout the Middle Ages, even up until the Norman Conquest , but as Christianity became the dominant religion the nature of kingship shifted in line with new religious practices. Many of Penda’s contemporaries were using Christianity as a “state religion” to unify their kingdoms. By bringing all those under their rule together under one religion, kings were able to create stability and peace in their territories, and the support of the Church would have bolstered the ruler’s hold on their throne by bringing them into a network of power that extended beyond the borders of their kingdom. Penda however, chose not to follow the example of his peers and convert to Christianity, nor did he use the paganistic Germanic religions in a similar way by enforcing them as a state religion.

Penda undoubtedly adhered to these pagan cults on some level, although there is no evidence as to how devout a follower he was. It has nevertheless been suggested that perhaps Penda’s reluctance to convert to Christianity was because he did not see Christ as a suitable divine patron for a warrior king such as himself, particularly due to his recurrent victories over Christian kings. Anglo-Saxons saw divine power as tied to political power and the successes or failures of kings were a reflection of the god to which they held allegiance, so choosing a religion was almost like choosing political allies, where a ruler must forge the most beneficial alliance to secure their reign. Penda, it seemed, did not see Christ as the most powerful ally available to him.

Detail from stained glass window depicting the death of Penda of Mercia at Worcester Cathedral. (Violetriga / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Penda the Brytenwalda: Inclusivity During Penda’s Reign

Penda’s defiant refusal to convert may actually have been a clever political decision, rather than a stubborn adherence to paganism and idolatry. By the latter half of his reign, Penda’s Mercian empire had expanded across vast distances and comprised of tributary kingdoms with rulers and subjects of varying religious beliefs. Many were Christian kings, but while some ascribed to the Roman Catholic version of Christianity others adhered to a slightly different Celtic version brought over from Ireland. It was not a viable option for Penda to try and unify all those over whom he ruled under the one religion, as whichever religion he chose would earn him the displeasure of at least one of his under-kings.

That is not to say that Penda rejected Christianity entirely. Quite the opposite seems to have been the case. Even Bede, who denounced Penda as an enemy of the godly, attributed a certain integrity to Penda when it came to religious matters:

“King Penda did not forbid the preaching of the Word, even in his own Mercian kingdom, if any wished to hear it. But he hated and despised those who, after they had accepted the Christian faith, were clearly lacking in the works of faith. He said that they were despicable and wretched creatures who scorned to obey the God in whom they believed .”

Penda also appears not to have resisted the conversion of his son Peada, whom he had made king of the Middle Angles and whose baptism is described in detail by Bede. If Penda were truly the militant heathen that 20th century scholars believed, he would not have ruled with such an attitude of religious inclusivity and tolerance as we see here. Diversity and inclusivity actually seem to have been the cornerstone of Penda’s success as a ruler.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles refer to an over-king such as Penda as brytenwalda, a term which meant “wide-ruler.” Penda was a “wide-ruler” in more than a territorial sense, ruling over not only a religiously diverse group of subjects, but an ethnically diverse one as well. In an era when tensions were high between the Britons and Anglo-Saxons, Penda had an unusually high number of allies among his neighboring British kings, with the king of Gwynedd, Cadwallon, being one of his staunchest allies.

Polarization between the races does not appear to have been as pronounced in Penda’s Mercia. Anglo-Saxons and Britons co-existed amicably under his rule. Relations between Mercia and the British kingdoms were largely peaceful in Penda’s time too, and Penda of Mercia was on friendlier terms with many of his British neighbors than his Anglian ones. In several Welsh poems dating from the era, Penda was even given the fond nickname of Panna ap Pyd , meaning “Penda son of Danger.” This paints a somewhat different image of Penda as a ruler than the overwhelmingly negative one presented by Bede.

Penda of Mercia seems to have had different ideas than Bede about what it meant to be English. Based on the evidence at hand, his England was more inclusive and pluralistic, less concerned with religious faith or ethnicity and more with personal integrity. Personal relationships were crucial in early Anglo-Saxon politics, when processes of government were conducted largely in person and relied upon the mutual goodwill between rulers and elites. Penda’s ability to harmoniously hold together such a large collective of small kingdoms under Mercian rule suggests he was a master of navigating this world of personal politics, earning him the support and loyalty of under-kings from all across the British Midlands.

If we look further afield than Bede’s narrow account of Penda’s rule, we can start to paint a picture of a man who was more than rex perfidus , the traitorous king who was a pagan scourge on a blossoming Christian England. Instead, the Penda we can start to evidence was the brytenwalda, who presided over a court where all were welcomed, a place where people of diverse languages, religions, ethnicities and cultures all met and mingled together.

Penda may have been a king of military ambition. In fact, his successes on the battlefield earned him a reputation for savagery that put him firmly on the wrong side of history for many centuries. However, Penda was much more than the last bastion of an uncivilized, pre-Christian England. Penda of Mercia was a king of the people, an expert politician and a tolerant, inclusive leader who was in some ways ahead of his time. The Mercian empire he built would go on to define England’s political landscape for centuries to come.

Top image: King Penda of Mercia. Source: breakermaximus / Adobe Stock

By Meagan Dickerson

References

Bede. 1955. A History of the English Church and People. Trans. Leo Sherley-Price. Penguin.

Ford, Judy Ann, and Robin Anne Reid. 2009. “Councils and Kings: Aragorn’s Journey Towards Kingship in JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings ” in Tolkien Studies 6, no. 1.

Singer, Mark Alan. 2006. Holding the border: power, identity, and the conversion of Mercia . PhD dissertation, University of Missouri–Columbia.

Tyler, Damian. 2005. “An early Mercian hegemony: Penda and overkingship in the seventh century” in Midland History 30, no. 1.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 8th, 2021

November 8th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: