From all the ancient inhabitants of the British Isles, the Picts remain the most mysterious and continue to be a crucial focus for many researchers, archeologists, and historians. The history of these Celtic-speaking peoples is full of enigma. These warlike tribes had no established and developed writing system, and much of what we know about them today comes from outside sources, many of which are hazy at best. So, what do we know about these peoples of Ancient Scotland? Well, one thing that slipped through time is an extensive list of all the purported kings of the Picts. One such king is Drust I, son of Erp, a legendary leader of the Picts and certainly one of the kings with an interesting background. However, the information we know about Drust I is scarce at best, or is it?

This elegant piece of metalwork may have existed during King Drust I’s rule and is part of the St Ninian’s Isle Treasure. (Johnbod / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Obscurity Of Pictish History And Mentions of Drust I

The “Pictish Chronicle” is a very old, early medieval manuscript that is dated to the reign of Cináed mac Maíl Coluim, better known as Kenneth II , the king of Scotland from 971 to 995 AD. By this time in history, it can be safely assumed that the Pictish identity in the region of Scotland was hazy at best, and mostly phased out, assuming somewhat of a mythical role. The rapid progress of Gaelicization was underway, meaning that the Gaelic language quickly overshadowed and replaced the old Pictish language , which was much like the Brythonic language of old.

Around this time the name “Alba” also came into use, replacing the previous names for the lands of the Picts. Nevertheless, it is agreed that the Pictish Chronicle does include a mostly historic list of previous rulers amongst the Picts. And although they were mostly separated into distinct clans or tribes, which often warred and raided each other for cattle, in times of hardships they banded together and were ruled over by a single leader.

Historians agree that the “Chronicle” is almost entirely historical after the part which mentions King Brude , son of Maelchon, who reigned between 554 and 584 AD. However, the chronicle goes back way beyond this ruler, and, if correct, could be an important insight into the history of the Picts.

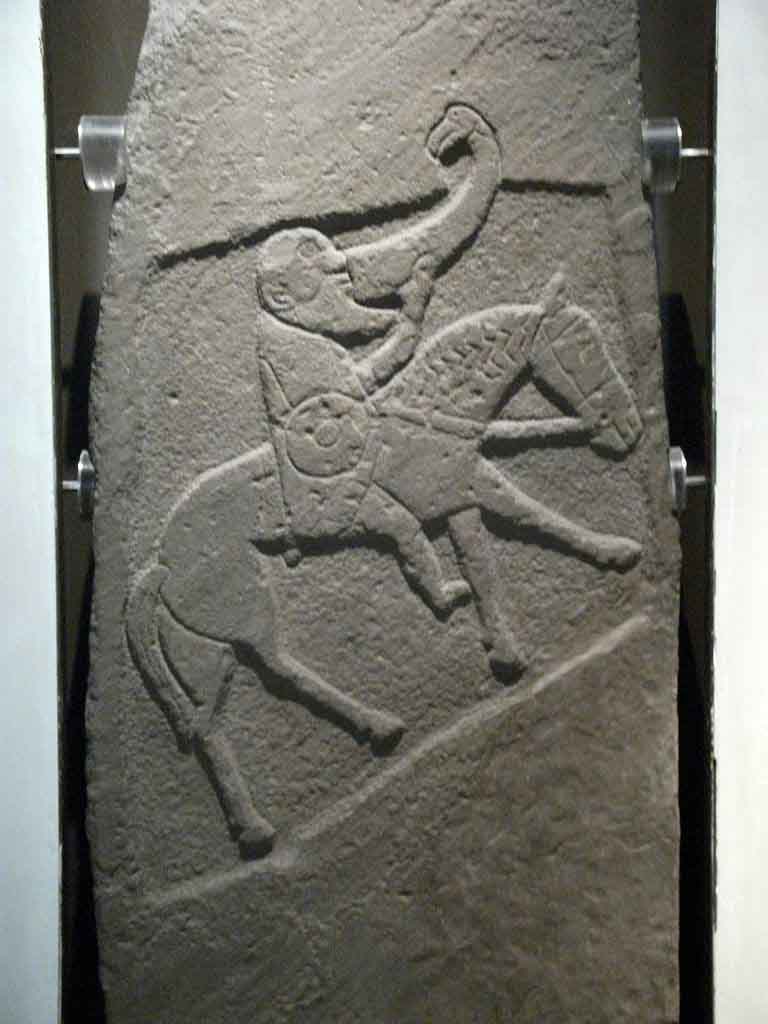

This Pictish stonework, on the famous Bullion Stone in Scotland, is generally thought to depict Drust I on a horse. (Johnbod / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The name of Drust is often recorded in different spellings: Drest and Drust being the most common. The name of his father is also recorded as either Erp, Irb , or Urb. The name itself is often mentioned amongst the Picts, with numerous kings bearing the exact same name. What is more, the name is vouched for amongst all the peoples of the British Isles.

In regard to the Picts, the name is given to a good number of somewhat mysterious kings. Some argue that the name can be connected to that of Tristan, the famed hero of Arthurian legend. The “Drust” version of this name is distinctively Pictish, and is also recorded as Drustan (i.e., Tristan), Drost, and Droston, and is almost exclusively a royal name. It also appears in the Welsh language and history, as Dryst, Drystan , and Trystan.

In the chronicle, Drust I, son of Erb, was an early king of the Picts, ruling in a time when the Romans were leaving Britain. It was a time of rapid change and characterized by a somewhat chaotic, disorganized state of affairs. It is likely that Drust I arose as a competent leader who could unite his people and capitalize on the situation.

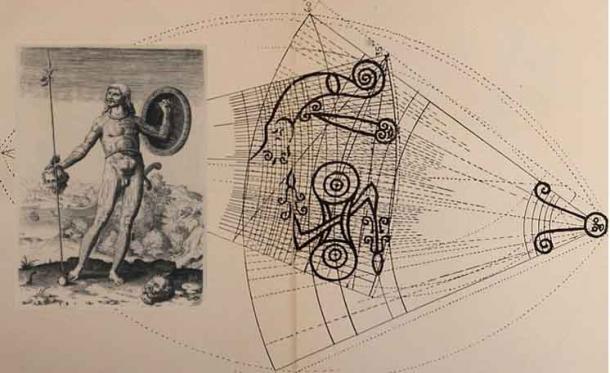

Main – Archaic carvings, a common symbol of Pictland as seen at Anwoth, Scotland. Inset – Theodor de Bry, Celtic or Pict Warrior, representative of Drust I. Source: Internet Archive Book Images /Public Domain

He is widely known as the “ King of One Hundred Battles, ” since the chronicle states that he “fought a hundred battles and lived a hundred years.” His actual historical reign is cited variously, with the most commonly accepted one being from 412 to 452 AD. One thing that is crucial about Drust’s reign is the fact that it was seemingly under his auspices that Christianity was first introduced amongst the Picts.

This was done by Saint Ninian (died 432 AD), whose life does coincide with the period of Drust I’s alleged rule. This was perfectly summed up by an early Scottish historian, Thomas Innes, whose work “Critical Essay on the Ancient Inhabitants of the Northern Parts of Britain” from 1729 is one of the crucial takes on this matter. In it, he writes:

“By this calculation it appears that it was during the reign of this Drust (Durst) that the gospel was first preached to the Picts by St. Ninian, in the beginning of the fifth century, and afterwards by St. Palladius and St. Patrick to the Scots and Irish, betwixt A.D. 430 and 440. And here ends the first part of the abstract of the Pictish Chronicles, which contains the account of the succession of their kings in the times of ignorance preceding their conversion to Christianity, when, it is like, they first received the use of letters.”

Another example of Pictish metalwork from the St Ninian’s Isle Treasure. (Johnbod / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Drust I Stood At The Head Of The Furious Picts

While a lifespan of one hundred years seems a bit unlikely and mythical for that ancient period, the “one hundred battles” aspect could very well be true. What little we can piece together from history indicates that Drust I was very active in military campaigns.

It is most likely that it was this very king that was responsible for the constant Pictish raids to the south, which were so critically mentioned by Gildas the Wise in the 6th century. Gildas left a highly important insight into the “ Groans of the Britons” (Gemitus Britannorum) , a historical plea of the Britons to the departing Roman military. It was a request for aid and was made between 446 and 454 AD, roughly coinciding with the reign of Drust I, son of Erp.

The Britons complained about the incessant incursions and raids by tribes of Picts and Scots. As the Roman military gradually withdrew southwards and then out of Britain, these northern tribes exploited the lack of military presence and penetrated deeply to the south, raiding and pillaging. The famous Briton plea states amongst other things: “ The barbarians drive us to the sea, the sea drives us to the barbarians; between these two means of death, we are either killed or drowned.” The barbarians here are the Picts.

Certainly, the Britons responded to this threat as best as possible and sought ways to remedy the growingly chaotic situation resulting from the raids. It is widely agreed that due to these Pictish incursions, likely led by Drust I himself, the Britons were left no choice but to hire more and more Anglo-Saxon mercenaries to battle this threat from the north. This in turn led to increased Anglo-Saxon presence in Britain, and their gradual settlement there.

The famous Pictish Aberlemno Serpent Stone. (Catfish Jim and the soapdish at English Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Ultimately, as a result there was a huge increase of Anglo-Saxon culture and settlement in Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries AD. Drust I was seemingly quite capable of protecting his southern borders against Britons, Anglo-Saxons, and the encroaching Gaels. He not only led offensive campaigns to reduce these threats, but also established fortified harbors along the coastlines of his land in order to protect them from maritime incursions.

One location in Scotland is today believed to be the main fort of King Drust I. It is today known as “Trusty’s Hill,” and is located near the town of Gatehouse of Fleet in the parish of Anwoth, in the district of Dumfries and Galloway. Here it is important to note that the name “Trusty” is a corruption of the name “Drust.” Thus, the location is literally called “Drust’s (Drusty’s) Hill.”

The fort is not too well preserved, although some remains of it can be seen. It was partially excavated in 1960 by one Charles Thomas, who deduced with certainty that the fort dates to pre-Roman times, i.e., well before the reign of King Drust I. Archeological excavations yielded traces of high-quality metalwork and large-scale feasts, which could indicate that this was an important and perhaps royal center.

Furthermore, a carved Pictish stone stands on this location, at the entrance into the fort. The stone is carved with well-preserved Pictish symbols: a lavish “double disc with a Z-rod,” an elaborately carved sea creature, and a representation of a Pictish dagger. This Pictish stone is one of the very few that were discovered so far south, outside the heartland of the Picts. It might correlate to Drust I’s proposed raids and southern incursions, which became such a big problem for the Britons.

Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill, one of the few places in Scotland to be clearly associated with Drust I. (Billy McCrorie / Pictish Symbols at Trusty’s Hill )

Amidst A Historical Turning Point: Picts And Romans

As the first, most likely, historical king of the Picts, Drust I is also mentioned in Irish sources, chiefly the Annals of Clonmacnoise (Annála Chluain Mhic Nóis ). This is an early medieval manuscript that was later translated into English, and it details the historic events in Ireland and the region from the supposed creation of time until 1408 AD. In this chronicle is mentioned Drust mac Erp (Drust son of Erp), the Pictish king who allegedly ruled for 29 years and died in 449 AD. It also states that it was in the nineteenth year of Drust I’s rule, around 435 AD, that Saint Patrick’s mission arrived in Ireland.

But once we connect these dots we can clearly understand that King Drust I was an able Pictish leader that rose up and managed the volatile situation that emerged in the early 400’s AD. As the Roman military presence waned and altogether ceased, and especially when the garrisons on Hadrian’s Wall were abandoned, the way was open for the warlike tribes of the north, whom the Romans could never fully subdue, to descend southwards and harass the vulnerable Britons.

Around this time, it is documented that the Roman signal stations on the Yorkshire coast were burned and destroyed. This occurs in the early 400’s and could very well be one of the initial moves by the Picts of King Drust I.

Another thing we know about Drust son of Erp is the fact that he exiled his own brother to Ireland. This man was known as Nechtan Morbet (Nechtan “ of the Speckled Sea ”) and was either exiled or fled to Ireland. This could be evidence that Drust and his brother feuded over the rule of the Picts. Nechtan later returned to his home and eventually became the king of the Picts, ruling from 456 to 480, most likely after his brother died.

It is said that Nechtan founded the village of Abernethy ( Obar Neithich ), which was at one time a capital and major political and religious center of the Picts. An early monastery founded there was erected on land granted by King Nechtan, son of Erp. The Pictish Chronicle records this of Nechtan:

“Nectonius, living in a life of exile, when his brother Drest expelled him to Ireland , begged Saint Brigid to beseech God for him. And she prayed for him, and said: “If thou reach thy country, the Lord will have pity on thee. Thou shalt possess in peace the kingdom of the Picts.”

A Pictish stone in the Museum of Scotland collection showing what could also be King Drust I. (Johnbod / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

King Drust I: A Leader Immortalized By His Deeds

Pictish history remains largely obscured by time. The lack of written heritage, and due to the turbulent history of the British Isles, the fate of the Picts was largely doomed from the start. What little we can piece together is fragmented and obscure, and closely intertwined with myth and legends.

Nevertheless, if we broaden our horizons and view the corresponding historical events in the region, we can with some certainty narrate the story of early Pictish kings.

Drust I, son of Erp, is one such figure. Viewing the historic events unfolding during that time, we can by all means label him as a historical figure. The King of a Hundred Battles certainly seems as a logical and plausible epithet, one which this king earned by exploiting the vacant space left by the retreating Romans, to unite the Picts under one banner and wreak havoc amongst the vulnerable Briton tribes.

And it could be very well likely that it was these actions by King Drust I that led to the gradual settlement of the Anglo-Saxons in Britain. And that itself was one of the defining moments in the entire history of the British Isles. It led to the emerging history of the English people, and thus the history of the world as well.

Top image: Celtic warrior. Source: jozefklopacka / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

References

Dunbavin, P. 1998. Picts and Ancient Britons: An Exploration of Pictish Origins. Third Millennium Publishing.

Drust. Oxford Reference. Retrieved 23 Jan. 2021. [Online] Available at:

https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095732413

Gardiner, S. R. 1892. A Student’s History of England: From the Earliest Times to 1885, Volume 1. Longmans, Green and Company.

Henderson, R. 2016. Rex Pictorum: The History of the Kings of the Picts . Independent.

Mark, J. 2014. Drust I. Ancient History Encyclopedia. [Online] Available at:

https://www.ancient.eu/Drust_I/

Venning, T. 2013. The Kings & Queens of Scotland. Amberley Publishing Limited.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 31st, 2021

January 31st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: