Thanks to recent attention in popular culture, the story of King Aelle’s violent death at the hands of Ivar the Boneless in a type of ritual killing known as the “blood eagle” is well-known. The Vikings have long held a reputation for barbarity and bloodthirstiness, and not without good reason. Ritual killings such as the blood eagle are known to have been relatively common occurrences across Viking-era Scandinavia and the brutality of Viking raiders throughout Europe has been well-documented.

It is natural to assume, given the level of violence portrayed in both the historical record and popular culture, that the Vikings continued to practice ritual sacrifice after their invasion and settlement of Britain in the 9th and 10th centuries. However, it appears that the practice seems to have quickly died out. The question archaeologists and historians continue to ponder is whether the Vikings really ceased practicing human sacrifice in Britain, and if so then why? Was King Aelle the first and last Briton to fall victim to ritual sacrifice at the hands of the Vikings?

According to legend, King Aelle killed the Viking Ragnar Lodbrok by throwing him into a pit of snakes. Ragnar’s sons then performed the blood eagle on King Aelle. ( Public domain )

King Aelle and Human Sacrifice in the Historical Record

The ritual killing of human beings is a practice that many cultures around the world have historically performed as part of their religious rites, and most of them pre-Christian or pagan societies such as the Norse religion of the Vikings. Human sacrifice is most often associated with religious rituals (sacrifice meaning “to make sacred”), although there are some examples of hostages or prisoners executed in stylized rituals such as the blood eagle for non-religious purposes.

For the Vikings, human sacrifice seems to have been primarily associated with funerals and mortuary practices. It was nevertheless far more common for animal sacrifice to accompany Viking funerals. In fact, animal sacrifice was present in almost 80% of burials in Viking Scandinavia.

Evidence of human sacrifice is far more scarce. Written evidence from the Viking era is often vague, with some scholars interpreting references to the practice as literary motifs rather than actual occurrences. The exception being the 10th-century eye-witness account of the funeral of a Rus chieftain on the banks of the River Volga. Written by Ahmad Ibn Fadlan, it documented the sacrifice of a slave girl which most historians generally agree to be a true account of real events. No written evidence exists at all for human sacrifice in Viking Age Britain , and in fact the account of King Aelle’s death, which is nothing more than a vaguely worded piece of poetry, is the only evidence of possible human sacrifice in Britain found on record.

The poem, Knútsdrápa by Sigvat Thordarson, only briefly mentions the death of King Aelle at the hands of the sons of the Viking Ragnar Lodbrok in one line: “And Ívarr, who resided at York, had Ælla’s back cut with an eagle.” No mention is made however, of any such occurrence in any of the contemporary Viking Age records from Britain or Ireland and so it is now largely believed that this reference to the eagle is simply alluding to the presence of carrion-eaters on the battlefield, a common theme in Norse poetry.

The archaeological record has provided much more concrete evidence of human sacrifice occurring during the Viking Age. Although victims of human sacrifice can often be difficult to identify, clear evidence of the practice has been found in Viking burials in Scandinavia and combined with the evidence from Ibn Fadlan’s account has led experts to believe it was part of the social fabric of Viking society. But what of those Vikings who left their homelands to settle elsewhere? Did the settlers who came to Britain maintain the practices of their ancestors, or did they abandon tradition to adapt to their new environment?

Viking age mass grave from Ridgeway Hill, Weymouth. ( Oxford Archaeology )

Viking Burials in Britain

In most pagan traditions, cremations were the most common form of burial and cremation was certainly a part of Scandinavian sacrifice rituals. Ibn Fadlan’s account of the chieftain’s funeral describes how the dead man is placed in a temporary grave while preparations are made and the slave girl who volunteered to die with him is made ready for her journey. After 10 days of rituals and feasting, the chieftain is exhumed and brought onto the ship in which he is to be buried, then the slave girl is ritually killed and the entire ship set on fire with a mound raised over the ashes.

Cremation was a common practice in the pre-Christian societies of Britain, including the Vikings and Anglo-Saxons. However, while many large pagan Anglo-Saxon cremation cemeteries have been found, only one Viking cremation cemetery is known to exist in England, in Heath Wood, Derbyshire, as well as a few sporadic cremations found elsewhere in Britain. When searching for evidence of human sacrifice though, it is the inhumation burials (interring the whole body instead of burning it) which provide us with more evidence and there are several of these burial sites that have been uncovered from the Viking Age.

The largest Viking Age mass burial in Britain was found at Repton monastery in Derbyshire, which was the site of the winter camp of the Great Heathen Army between 873 and 874. The burial chamber occupied a disused building which was demolished so a mound could be built over the burial. It contained the bones of at least 264 individuals placed around a central grave, likely that of an important warrior or chieftain.

To the southeast corner of the mound was a separate grave containing the bones of four children aged between 8 and 17 years old, alongside the jaw bones of a sheep or goat. Although tests performed on the remains cannot confirm when and how these children died, it has been assumed by archaeologists that they were victims of ritual sacrifice because of the presence of animal bones, likely sacrificed for the burial, as well as their proximity to such an important burial site.

Another mass burial was found at Ridgeway Hill in Dorset, where the bodies of 54 decapitated males were buried with only 51 heads stacked to one side. The deceased ranged in age from their teens to their 50s, and none showed signs of battle injuries. It was therefore unlikely that they belonged to seasoned warriors, although most of the skulls had teeth decorations (filing) which were common among fighting men.

Despite the ritualized nature of the burial however, these men do not appear to have been victims of ritual sacrifice. Most of the individuals were suffering from infections or physical impairment such as osteomyelitis or fractured bones, kidney disease, and brucellosis (a highly contagious infectious disease contracted by ingesting unsterilized meat or milk). It is more likely these men were peasants or inexperienced raiders who were killed as a matter of convenience rather than for religious purposes.

The only certain example of human sacrifice found in the British Isles is on the Isle of Man at Ballateare. A man between 18 and 30 years old was buried in a mound and a woman of 20 to 30 years old was killed by a blow to the head, which sliced the back of her skull off. Her body was then placed on top of the burial mound 12 to 72 hours later with a 7 cm (2.75 in) layer of cremated animal bones, including those of a horse, ox, sheep, and dog, laid over the top and a grave marker placed in the middle. There are many other graves containing multiple individuals or parts of individuals that are possibly examples of ritual sacrifice, included in the burial as grave goods, but for most of these burials the evidence is unclear.

Woman’s Skull from Ballateare burial on the Isle of Man, believed to be the only clear example of a human sacrifice in the British Isles. ( Viking Archaeology )

What Markers Indicate a Sacrifice?

There are several characteristics of a Viking grave that might lead archaeologists to believe it contained a human sacrifice, one of the most compelling being the presence of animal remains. Animals were central to the worldview of Germanic and Norse peoples, particularly in a spiritual sense, and animals and humans were viewed as being one and the same rather than two separate categories of being. Domestic animal bones are a common find in Viking graves, most often horses, cows, and sheep or goats and usually only parts of the animal, although whole animal remains can be found in richer burials.

These animals are sacrificed specifically for the burial and seem to act as companions in the journey to the afterlife for the deceased. This is why the remains of companion animals such as domestic dogs are often found, although the horse is the most common companion animal to be sacrificed at Viking funerals. Horses are particularly significant in Norse religion, both as symbols of fertility and through association with death. Odin’s warhorse Sleipnir could travel between the realms of the living and the dead, and figures heralding death often appear mounted on grey horses.

Horse burials, either the whole animal or parts of it, are most often associated with young adult male burials and was once thought to have indicated a warrior’s grave, but this is no longer the case. A number of female graves contain horse burials and some of the remains belong to draught horses, sometimes buried with their harnesses, rather than warhorses. It is more likely that horse sacrifices are associated with social status rather than occupation, which appears to be the case for human sacrifice as well.

In the past, archaeologists assumed that gender was another marker of human sacrifice. That is, if the body of a male and female were found together, particularly if the female died violently such as the grave at Ballateare, then the female was assumed to have been a sacrificial victim killed for the funeral of the male. The record Ibn Fadlan made of the Rus Chieftain’s funeral has fuelled this assumption: the act of “retainer sacrifice”, in which a slave girl volunteers to die with her master as a tribute to him, fits with assumed social structures and gender norms for Norse cultures of this period.

Elements of this funeral described by Ibn Fadlan have been found in Viking graves in Britain – the violent nature of the victim’s death (the slave girl died by multiple stab wounds) followed by cremation – and therefore assumed to indicate human sacrifice . For example, at Withorn Monastery in Scotland, the burial of an infant was found next to a collection of bones from several dismembered adult human skeletons and the forelimb of a cow, all covered by a cremation layer containing the remains of four other humans. However, without more conclusive evidence it is impossible to say for certain whether these remains are the victims of ritual sacrifice.

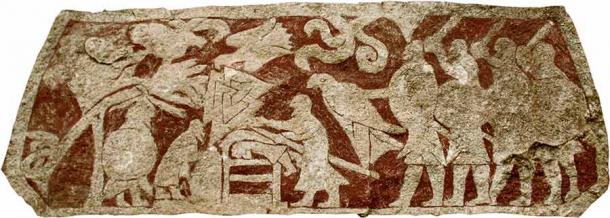

A Stora Hammars stone dating from the 7th century AD, possibly showing a medieval depiction of the Viking blood eagle torture. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

What Does Sacrifice Mean?

As we can see from the archaeological record, there is very little evidence of ritual human sacrifice occurring in Viking Age Britain at all and this begs the question, why? Viking funerals were important social displays of status, particularly for noblemen, and symbolized not only the role and authority of the deceased but also the inheritance process of their heirs. From what historians can gather, a ritual sacrifice on such an occasion was a potent symbol of status and wealth for both the deceased and the victim chosen for sacrifice in Scandinavian culture. What would cause the Vikings to abandon this practice once they reached the shores of Britain?

It appears to have been a case of adaptation, as the first waves of Viking settlers came to Britain and were faced with a new reality. Despite the relative lack of Viking graves found in Britain, compared to Scandinavia, there is a clear masculine emphasis in funerary practices: weapons vastly outnumber any other category of artifact found in Viking graves in Britain, and in all burials containing weapons the remains were male. Weapons in Viking culture were part of a complex web of symbolism that included masculinity and violence, but also represented ancestry and connections with particular deities.

Weapon burials seem to have been used as a means of connecting with the past in a new land where the sense of identity and ancestry could not be felt as strongly. This was also as a method of transferring power and property from one generation of conquerors to the next, to ensure social stability during a time of chaos and upheaval. The Vikings of Britain likely saw these as the most important purposes for their funerals, mediating the process of conquest by establishing legitimacy and rights to inheritance. A ritual sacrifice might have seemed like an excessive or irrelevant display of wealth and privilege in the funeral proceedings of a people only newly-arrived to the land they lived on.

That is not to say that ritual sacrifice wasn’t practiced in Britain, as the evidence surely shows that it must have been on some level. Those sacrifices that did occur however, are most likely to have been in the style of King Aelle’s alleged death . This was not an act of religious significance but rather a brutal reminder to the local population of their defeat and subjugation, executing prisoners and hostages or using local slaves as human sacrifices such as the four children found buried in the mass grave at Repton. Ultimately however, the practice of ritual sacrifice died out within a century or two, along with other pagan practices , as the Vikings assimilated into the local population, marrying local women and adopting local Christian customs and religion.

Top image: Detail from Stora Hammars, possibly showing a medieval depiction of the Viking blood eagle torture, the method believed to have been used to kill King Aelle. Source: CC BY-SA 3.0

By Meagan Dickerson

References

Bond, Julie M., and Fay L. Worley. 2009. “Companions in death: the roles of animals in Anglo-Saxon and Viking cremation rituals in Britain.” In Social archaeology of funerary remains , eds. Gowland, Rebecca, and Christopher Knusel. Oxbow Books.

Hadley, Dawn M. 2008. “Warriors, heroes and companions: negotiating masculinity in Viking-Age England.” Anglo-Saxon studies in archaeology and history 15.

McLeod, Shane. 2018. “Human sacrifice in viking age Britain and Ireland.” Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association 14.

Moen, Marianne, and Matthew J. Walsh. 2021. “Agents of Death: Reassessing social agency and gendered narratives of human sacrifice in the Viking Age.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 31, no. 4.

Sikora, Maeve. 2003. “Diversity in Viking Age Horse Burial: A Comparative Study of Norway, Iceland, Scotland and Ireland.” The Journal of Irish Archaeology 12/13.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 5th, 2022

March 5th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: