True leadership knows no gender and despite societal condemnation or restrictions of the gods, powerful women have risen to the challenge and stepped up to take the reins of governance firmly in their delicate hands. Queens in their own right, their reigns are characterized by progress, wealth and prosperity, intellectual mining, civil construction, military genius, and even human sacrifice. A walk through 2000 years of history delivers some of the most outstanding and famous queens, who left a legacy as worthy and impressive as the monuments they had constructed as their final tombs.

1500 BC: Hatshepsut, The Famous Queen Who Became King

The Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose I and his queen Ahmose bore a princess named Hatshepsut in 1508 BC. She was the only child of the pharaoh and his first wife and if the lineage of rule was passed on to daughters, she would have been first in line to inherit the royal crown at the age of 12 when her father died. However, Hatshepsut was married to her half-brother Thutmose II, to become his principal wife and queen. They bore a daughter, Neferue, and Thutmose II had a son, Thutmose III, with a concubine. At the age of 27, Thutmose II died and Hatshepsut became regent for her stepson Thutmose III.

The gods of Egypt had allegedly decreed that the king’s role could never be fulfilled by a woman. The Egyptian pantheon consisted of 24 Egyptian goddesses, 26 male deities, and six androgynous gods. The most powerful Egyptian goddess was Isis, and then there was Hathor, Bastet, Maat, Nut, and many more. Most probably, the ‘decree of the gods’ was imposed by male priests and politicians.

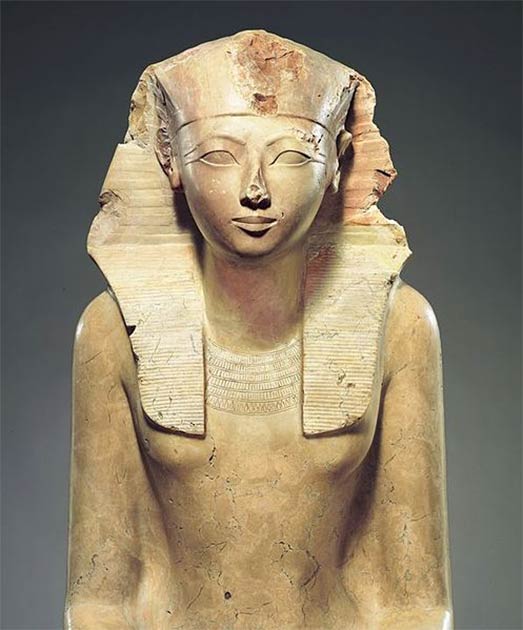

Statue of the famous female ruler, Hatshepsut. ( CC0)

How quickly they were to forget Sobekneferu, another woman who ruled as pharaoh during the 12th dynasty, albeit only for four years. Possibly Hatshepsut reasoned that the 24 female deities would back her up, so by 1437 BC she defied the decree and had the nemes crown of Pharaoh placed firmly on her head.

To gain legitimacy in the eyes of her subjects, and perhaps reach a compromise with her courtiers, Hatshepsut changed her name, which meant ‘Foremost of Noble Ladies’, to the male version Hatshepsu. She is depicted as wearing male attire and even sporting a false male beard. Traditionally, statues of men were painted with a deep red pigment and women with a lighter yellow pigment, but interestingly, statues of this ruler were painted a unique orange skin tone, a fusion between the two colors.

Whatever her exterior cosmetic trimmings, Hatshepsut was an effective and highly successful ruler for 21 years. Her major achievement was to re-establish the trade routes that had been disrupted during the Hyksos occupation of Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period (1650-1550 BC), between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. Trading with the Land of Punt brought wealth and prosperity to Egypt.

She commissioned hundreds of building projects throughout Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, of which the most monumental was the mortuary temple complex at Deir el-Bahri, on the West bank of the Nile. She planted myrrh trees, which she had secured from Punt, at this complex. Regarding her foreign relations policy, she mostly maintained diplomatic, peaceful relations, but she also led military campaigns into Nubia and Canaan, and she sent raiding parties to Byblos and Sinai.

Statue of Hatshepsut at her temple at Deir el-Bahri. ( sootra /Adobe Stock)

Hatshepsut died around 1458 BC, aged in her late 40s. Her stepson Thutmose III tried to eradicate all evidence of her rule and it was only in 1822 AD, when hieroglyphs on the walls of Deir el-Bahri were decoded, that her existence and astonishing rule was revealed. While the mummies of Thutmose I, II, and III were all discovered at DB320, in the Valley of the Kings, Hatshepsut was nowhere to be found.

Dr. Zahi Hawass revisited the tomb known as KV60, where two mummies had been discovered by Howard Carter. He found a small box containing a decomposed internal organ and a tooth. Modern scans of the female mummies indicated one of them had an empty tooth socket, to which the discovered tooth was a perfect match. Through modern forensic testing the mummy was positively identified as Hatshepsut in 2007. The Queen Pharaoh had been restored in her own right.

1000 BC: Queen of Sheba, Founder of the Ethiopian Solomonic Dynasty

Although she has almost reached cult status as a legendary figure, the Queen of Sheba is recognized in all three of the Abrahamic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Yet the location of Sheba has always been disputed. Some place it in southern Arabia as the Kingdom of Saba (modern-day Yemen), and Arab sources refer to the Queen of Sheba as Balqis or Bilqis.

Around the middle of the first millennium BC, there were Sabaeans also in the Horn of Africa, in the area that later became the realm of Aksum, which is located in Ethiopia. Thus, it is Ethiopia who claims the Queen of Sheba, named Makeda, as the mother of their nation. The identification of Ethiopia as Sheba is supported by the first century AD Jewish historian, Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews who identified Saba as a walled, royal city of Ethiopia, which Cambyses II renamed as Meroë. This name is found in the 14th century Kebra Nagast (‘The Glory of Kings’), which was written in the 14th century and considered to be Ethiopia’s national epic.

The Queen of Sheba is purported to have had access to unknown wealth. In the Qur’an a hoopoe, informs King Solomon about the land of Sheba, governed by a woman, who “has been given of all things, and she has a great throne”. 1 Kings 10:10 of the Hebrew Bible confirms her riches as such:

“And she gave the king 120 talents (about four tons) of gold, and of spices very great store, and precious stones: there came no more such abundance of spices as these which the Queen of Sheba gave to King Solomon. / And the navy also of Hiram, that brought gold from Ophir, brought in from Ophir great plenty of almug trees, and precious stones”.

17th century AD painting of the famous Queen of Sheba from a church in Lalibela, Ethiopia. (Magnus Manske/ CC BY SA 2.0 )

There is no doubt that both the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon were aware of the other’s riches. Who was going to bend the knee to the other’s magnificent throne first? Although the queen was aware of her kingdom’s military strength, she opted for a more diplomatic approach and decided to send King Solomon gifts. The gifts were rejected by Solomon, who said: “Do you provide me with wealth? But what Allah has given me is better than what He has given you. Rather, it is you who rejoice in your gift”.

In male fashion, Solomon then threatened to take military action if the queen still did not acquiesce to his summons. Whether her curiosity got the better of her one would never know, but the Queen of Sheba decided to travel to Jerusalem and brought with her “a very great train, with camels that bare spices, and very much gold, and precious stones”. She asked King Solomon three riddles to test his wisdom and he in turn tried to trick her by making her walk over a floor of glass, which she mistook for water. Once the trickery and riddles were set aside, the two regents got to know each other more intimately.

Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (Gates of Paradise). (Sailko/ CC BY 2.5 )

The Queen of Sheba fell pregnant by King Solomon and bore him a son, Menilek, who became king, thus founding the royal Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia, which ruled until the deposition of Haile Selassie I in 1974. In Yemen, archaeologists excavating the ancient Sabaean Awwām Temple, called the Sanctuary of the Queen of Sheba, found no reference to the Queen of Sheba in the many inscriptions there and the British Museum states there is no archaeological evidence for her existence, yet. Perhaps, like Hatshepsut, the Queen of Sheba may reveal herself in a lost tooth or some other artifact, waiting to be reconstructed by modern technology.

69 BC: Cleopatra, The Intellectual Queen of Egypt

Everyone is familiar with the legend of Cleopatra, famous for her beauty, her habit of bathing in donkey’s milk, and seducing both Julius Caesar and Mark Anthony of Rome. Yet few recognize that Cleopatra VII was considered one of the most intelligent women of her time. Cleopatra was born in 69 BC to pharaoh Ptolemy XII. Like her predecessor Hatshepsut, she became pharaoh, but she had to outwit her sibling to seize the throne of Egypt.

It seems the Greek Ptolemies were less bound by the ancient Egyptian deities’ decree not to appoint women as rulers. In 81 BC, Ptolemy IX died and was succeeded by his daughter Berenice III. However, the Egyptian court still objected to a queen reigning alone, and she married her stepson, Ptolemy XI, who promptly had her killed. Berenice’s namesake Berenice IV, Cleopatra’s older sister, claimed the throne when their father, Ptolemy XII accompanied by Cleopatra, made a state visit to Rome. Berenice was killed in 55 BC upon his return.

Ptolemy XII ruled until his death in 51 BC, when Cleopatra and her younger brother Ptolemy XIII inherited the joint custody of Egypt. Their disagreement led to a civil war. Julius Caesar, the Roman consul, intervened but was besieged, along with Cleopatra, by Ptolemy XIII. Caesar’s reinforcements lifted the siege and Ptolemy died in the 47 BC Battle of the Nile.

A posthumous painted portrait of Cleopatra VII of Ptolemaic Egypt from Roman Herculaneum, made during the 1st century AD, i.e. before the destruction of Herculaneum by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius. (Ángel M. Felicísimo/CC BY 2.0)

Cleopatra’s sister Arsinoe IV was exiled to Ephesus for her role in carrying out the siege, and later killed by Cleopatra’s lover, Mark Anthony. Caesar appointed the 22-year old Cleopatra and her 12-year old youngest brother Ptolemy XIV as joint rulers, but Cleopatra would have none of sharing the throne with a brother and had him assassinated in 44 BC. Clearly, she was a clever political strategist.

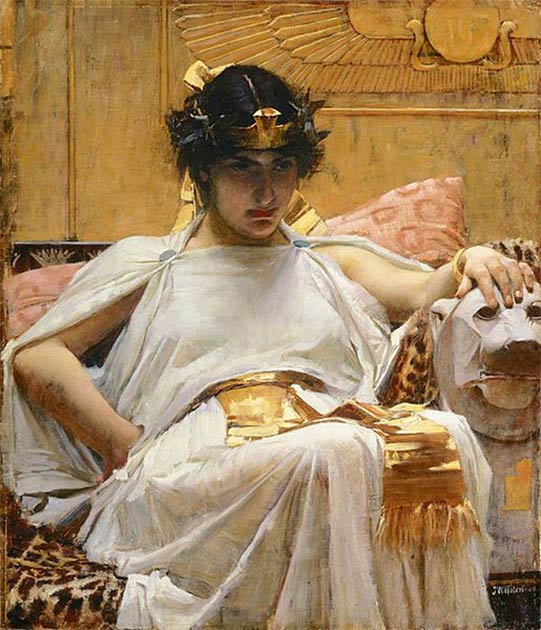

Cleopatra has been hailed as one of the most beautiful women on earth, but it seems her beauty was reflected in her intellect. Plutarch acknowledges in his Life of Antony , ( XXVII.2-3):

“For her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable, nor such as to strike those who saw her; but converse with her had an irresistible charm, and her presence, combined with the persuasiveness of her discourse and the character which was somehow diffused about her behavior towards others, had something stimulating about it. There was sweetness also in the tones of her voice; and her tongue, like an instrument of many strings, she could readily turn to whatever language she pleased …”

As a royal princess, Cleopatra’s childhood tutor was Philostratos, who taught her oration and philosophy. She was the first Greek pharaoh to learn ancient Egyptian, she could interpret hieroglyphs, and she was of course fluent in Greek – her native language – as well as the languages of the Parthians, Jews, Medes, Trogodyatae, Syrians, Ethiopians, and Arabs. She studied geography, history, astronomy, international diplomacy, mathematics, alchemy, medicine, zoology, economics and more. With an obvious flair for languages and given her history with Caesar and Mark Anthony, she probably accomplished Latin as well.

‘Cleopatra’ (1888) by John William Waterhouse. ( Public Domain ) Cleopatra is one of the most famous queens in history.

Like an ancient Estee Lauder, she manufactured cosmetics in her laboratory and wrote a few works related to herbs and cosmetology. Her work was well-known during the first centuries of Christianity, but sadly all her books were destroyed in the fire of 391 AD, when the great Library of Alexandria was incinerated. Cleopatra herself had studied as a student at the Library of Alexandria.

During the Roman Liberator’s War, Cleopatra sided with Mark Anthony and sailed at the head of her own fleet to his aid. Unfortunately, her ships were severely damaged in a Mediterranean storm and she arrived too late to participate in the battle. Her later alliance with Mark Anthony secured her the former Ptolemaic territories in the Levant, including nearly all of Phoenicia (modern-day Lebanon), Ptolemais Akko (modern Acre in Israel), the region of Coele-Syria along the upper Orontes River, and the region surrounding Jericho in Palestine, which she leased back to Herod. She also gained a portion of the Nabataean Kingdom, Cyrene along the Libyan coast, and Itanos and Olous in Roman Crete, proving once again what she lacked in military strength, she made up for in clever strategy.

Cleopatra was the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt and after her death in 30 BC, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. When Cleopatra died her intellectual legacy was transferred to her daughter with Mark Anthony– Cleopatra Selene. She married the future king Juba II of Mauretania, a great intellectual himself, who encouraged his wife to cultivate the memory of her great mother.

270 AD: Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra

Cleopatra’s intellectual legacy was passed on from generation to generation, finally to Zenobia , who seized rulership like her famous ancestor. At the time of Zenobia’s birth in 240 AD, Palmyra was a Roman province. Her names, Julia Aurelia Zenobia, indicate her Roman citizenship, granted previously to her father’s family.

Zenobia’s ascent to power began as the second wife of Septimius Odaenathus, Roman governor of Palmyra, who had defeated the Sassanian king, Shapur. Upon the assassination of Odaenathus and Hairan, his firstborn son from his first wife, in 267 AD by emperor Gallienus, Zenobia’s son, Vaballathus, became king of Palmyra, and Zenobia became regent. Like Cleopatra, Zenobia entertained intellectuals and philosophers at her court, she was generous towards her subjects and tolerated religious minorities, but where Cleopatra had expanded Egypt’s territories by clever manipulation, Zenobia expanded her territory by military maneuvers.

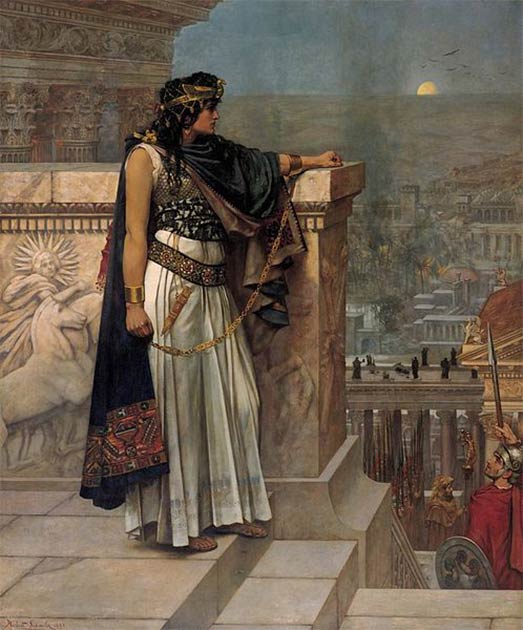

‘Queen Zenobia’s Last Look Upon Palmyra ’ (1888) by Herbert Gustave Schmalz. ( Public Domain )

During the third century AD, Rome experienced a severe crisis, dubbed the Imperial Crisis (235–284 AD) when the empire was besieged with invasions, rebellions, civil wars, plagues, and economic depression. Queen Zenobia saw the opportunity to capitalize on the situation, by expanding Palmyra’s territory and finally to achieve independence from Rome. Standing on her lineage from Cleopatra, she laid claim to the now Roman province of Egypt. Her claim was recognized by the Egyptian Timagenes, who rallied his troops to defeat the prefect of Egypt, Tenagino Probus. After annexing Egypt, Zenobia turned her armies to Anatolia, conquering Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon, on the way.

The Roman emperor Aurelian had no choice but to recognize the Palmyrene Empire, as he was facing a bigger threat in the West. Zenobia, still acting as regent for her son, had coins minted showing Vaballathus and Aurelian holding equal rank. Not long after, only Vaballathus and Zenobia herself featured on the coins. By 272 AD, Zenobia declared her son emperor and assumed the title of empress, an affront which convinced Aurelius to turn his armies to the East.

He defeated Zenobia at Antioch and Emesa. Zenobia first fled to her beloved Palmyra and then attempted to escape by camel with her son, but she was apprehended by Aurelian. The fate of the Palmyrene Queen after that is pure speculation; that she was paraded by Aurelian during his triumph, that she was granted a villa by Aurelius and that she married a wealthy Roman. She died after 274 AD, but her legacy is still celebrated as she is revered as a symbol of patriotism in Syria.

Marble statue of the famous queen Zenobia in chains. ( CC BY SA 3.0 )

500 AD: The Lady of Cao, Peru

In 1987, excavations at Huaca Rajada, Sipán, revealed intact tombs, with several mummies, of which the first was dubbed ‘The Lord of Sipán’. His jewelry and ornaments of gold, silver, copper, and precious stones indicated he was of the highest rank. There were two pyramids at Huaca Rajada, as at the later Moche site, discovered at El Brujo.

In 2006, at Huaca El Brujo (Sacred Place of the Wizard) on the northern coastline of Peru overlooking the blue Pacific, another mummy was discovered, but this time, she was a woman. The Lady of Cao, as she is called, had died in her mid-twenties about 1,500 years ago, probably due to a complication of childbirth. A second young woman, probably a sacrifice, was entombed with her.

The two main pyramids, Huaca del Sol and the Huaca de la Luna at El Brujo were once the center of social and religious celebrations of the pre-Inca Moche culture. When Peruvian archaeologists first began to discover images of Moche life depicted on the tomb walls, they were convinced that the images were metaphorical representations of cosmic events, as certainly no culture could have had powerful blood-drinking priestess mystics, who ruled such a society.

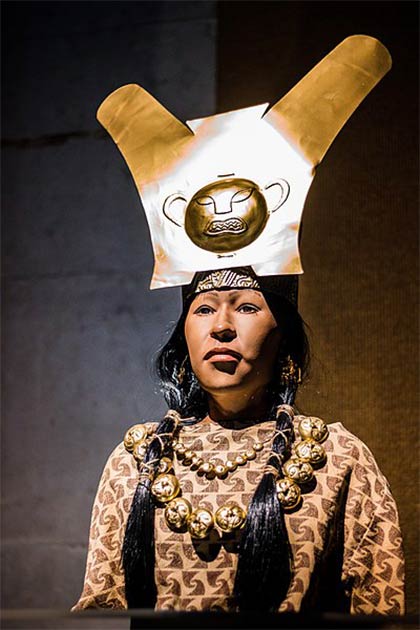

Reconstruction of the powerful female ruler known as the Lady of Cao. (Ozesama/ CC BY SA 4.0 )

Previously, it was thought that the society was ruled by men, after the discovery of the Lord of Sipán. However, one ritual depicted on the tomb wall shows tied-up, vanquished, naked individuals, marching up to the top platform of the great pyramid where their throats are cut, as a sacrifice to a supreme deity. Astonishingly, a great silver goblet, the mark of a ruler in Moche society, is used to collect the blood and then the blood is consumed by the priestess-queen. Not only the wealth of the artifacts, but actually the weapons found with the female mummy, indicate that she may have been a ruler.

What made the Lady of Cao even more remarkable, were her tattoos. The Moche did not mummify their dead deliberately, but the dry climate happened to preserve the Lady of Cao and her intricate tattoos. Although it is not believed that the more common members of Moche society were tattooed, it could certainly be inferred from this burial that the highest status members probably were, and the tattoos represented and strengthened the individual’s connection with the divine through sympathetic magic.

No-one knows the exact circumstances of the life of the Lady of Cao, but it is clear that she was awarded equal status in her death to that of the presumed male rulers. Like Hatshepsut, modern technology has brought the Lady of Cao back to life. With the help of 3-D printing a facial reconstruction of the priestess-queen now serves as a Peruvian model of female rulership.

Reconstruction of the Lady of Cao. (© Manuel González Olaechea y Franco/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

Top Image: Many famous queens have altered the course of history. Source: Atelier Sommerland / Adobe Stock

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 5th, 2021

January 5th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: