The Organization of Islamic Cooperation has long been considered an anti-Israel institute, to put it mildly.

It was established following an Australian tourist’s attempt to burn down Jerusalem’s Al Aqsa Mosque in 1969. Its members are the representatives of 57 Islamic states, including Turkey and Iran, and for the past four years the organization has been headed by Secretary-General Yousef Al-Othaimeen, a Saudi politician. In February, the organization rejected US President Donald Trump’s Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative, calling on its members not to cooperate with it.

On Monday, however, Al-Othaimeen sounded a very different tone.

In an interview to Sky News in Arabic, Al-Othaimeen said: “We need to think outside the box… This [Palestinian] issue has been going on for over 70 years. We have tried wars and throwing the Israelis into the sea; we have tried a lot. The new generation of our Palestinian brothers needs to try ideas that will lead to a solution to this problem, which is of interest to us all, but in new ways, ways that have not yet been tried, in order to reach a two-state solution with East Jerusalem as the capital of this state.”

Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) Secretary General, Yousef bin Ahmed Al-Othaimeen. (AP Photo/Emrah Gurel)

Al-Othaimeen then asked: “Why insist on the path of resistance and boycott and distancing? What should be distanced are the traditional and familiar ideas.”

A few months ago such statements would have been inconceivable. That they were uttered this week, by the head of this organization, shows how the Israeli normalization agreement with Sudan, and the earlier agreements with Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, have generated nothing short of a Middle East earthquake.

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, center, talks during a joint news conference with then Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah, left and Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) Secretary General, Yousef bin Ahmed Al-Othaimeen, right, following the extraordinary summit of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), in Istanbul, May 18, 2018. Turkey urged Muslim nations at the OIC summit to stand with the Palestinians against Israel, warning that the American decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital would only be the first among many moves against the Islamic world. (AP Photo/Emrah Gurel)

The world view of generations of Arabs in the region, in both Sunni and Shiite states, was shaped around the Palestinian issue and the conflict with Israel. Yet here before the astonished eyes of hundreds of millions of Muslim and Christian Arabs — and especially the Palestinians’ shocked gaze — that foundational worldview has collapsed. Suddenly, the Palestinians – who would wave the prospect of normalized relations with the Arab world as the carrot to try to convince Israel to resolve the conflict with them — now find themselves irrelevant. They woke up one morning to find that the presumed consensus, the very premise, the whole concept of Palestinian nationality is in real danger.

The Palestinian issue, having once been front and center in the Arab world, at the heart of strategy and policy-shaping in Sunni Arab countries, has been thrust into the margins, with leaders throughout the Arab world calling on them to recalculate their route. They are being taken to task, upbraided for having become a burden on the entire Arab world — a burden that quite a few Arab countries are now trying to shrug off, and quickly.

Bahrain Foreign Minister Abdullatif al-Zayani, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, US President Donald Trump and the United Arab Emirates’ Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan sign the normalization agreements between the countries on the South Lawn of the White House, September 15, 2020 (Avi Ohayon / GPO)

The first agreements, with the UAE and Bahrain, were shocking but not devastating, and comparatively easy for the Palestinian Authority to swallow. The decision-makers in Ramallah, headed by President Mahmoud Abbas, were inclined to take the blow and carry on. For a few days, Ramallah castigated the leaders of the UAE, especially heir apparent Mohammed bin Zayed, for their ostensible betrayal and duplicity, but then it was decided to take a step back.

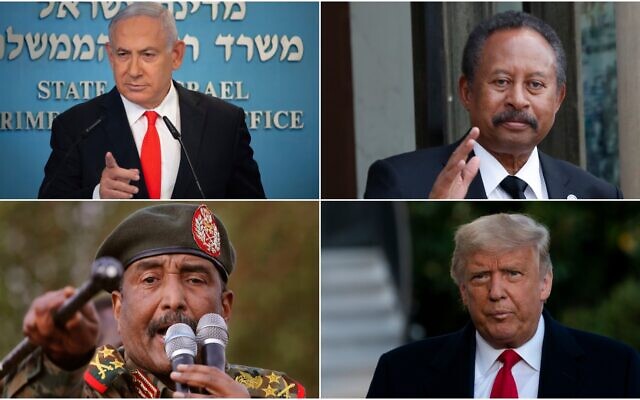

Clockwise, from top left: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at his office in Jerusalem, Sunday, Sept. 13 2020 (Alex Kolomiensky/Yedioth Ahronoth via AP, Pool); Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok at the Elysee palace in Paris, Monday, Sept. 30, 2019. (AP Photo/Thibault Camus); US President Donald Trump at the White House, Wednesday, Oct. 21, 2020 (AP Photo/Alex Brandon); Sudanese Gen. Abdel-Fattah Burhan, head of the military council, west of Khartoum, June 29, 2019 (AP Photo/Hussein Malla, File)

But then, last weekend, came the announcement that Sudan was also to normalize relations with Israel. Truly shaken, the entire Palestinian leadership went into a spin. Like a boxer who takes a massive blow but hasn’t yet fallen, the Palestinian Authority is trying to digest the news and its instinctive reaction of waving angry fists in the air is far from impressive. It seems to be digging into its entrenched positions, regardless of the cost, declaring that the Palestinians’ basic claims remain unchanged and that they have no intention of rethinking strategy.

Behind this stance, of course, looms Tuesday’s US presidential elections. If Democratic candidate Joe Biden is elected, then the PA would like to believe that any steps taken by Trump are no longer relevant and their cause will return to the center of the Middle East stage. If Trump is reelected, then “mourning will be declared here. Genuine mourning,” as a leading Palestinian commentator told me this week.

US President Donald Trump speaks with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on the phone about a Sudan-Israel peace agreement, in the Oval Office on October 23, 2020 in Washington, DC. President Trump announced that Sudan and Israel are making peace. (Win McNamee/Getty Images/AFP)

Indeed, a Trump victory may mark the end of an era: the end of the Oslo Accords era and the end of the Palestinian Authority in the form it has taken since 1994. If so, this will provide Israel and Israelis still celebrating the regional peace agreements with a reminder that the most difficult problem to solve — and certainly the most painful — was and still is the Palestinian issue.

That same commentator also posited that a Trump victory would probably lead to general elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council (al-Tashri’iyy al-Filastiniyy) followed (maybe) a few months later by presidential elections. And this is where the name of a chief contender for office comes in, one that that Israelis have almost completely erased from their consciousness: Marwan Barghouti.

Barghouti and the wafer

The last time elections were held for the presidency of the Palestinian Authority was in January 2005, two months after the death of Yasser Arafat. Almost 16 years have passed since then, during which the position has been filled by Abbas.

If elections are held because of a Trump victory, Fatah’s Central Committee will present a candidate — most likely Abbas himself. If Abbas, 85, does not run, for health or other considerations, potential heirs could include Mahmoud al-Aloul and Jibril Rajoub, but probably not Barghouti, who is serving life terms in an Israeli jail for direct involvement in five murders during the Second Intifada.

Barghouti, 61, is viewed as the architect of the Second Intifada, with its strategic onslaught of suicide bombings against Israeli civilians. He worked hard to generate it and fan its flames, and was a primary advocate of making it “military,” as they say in Arabic. In April 2002, he was arrested by an IDF Duvdevan unit at the home of his friend Ziad Abu Ein in Ramallah. (Abu Ein later died of a heart attack during a demonstration against Israel). He’s been in jail ever since.

Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, right, and Fatah leader Marwan Barghouti, in the West Bank town of Ramallah, December 31, 2001 (AP Photo/Mohammed Rawas)

A little over three years ago Barghouti helmed what should have been the largest hunger strike the Israeli prison system had ever known. It ended, however, with barely a whimper after its leader and symbol was filmed secretly scarfing down a chocolate-covered wafer.

This was a sweet moment for the Israeli prison system that had caught him chocolate-handed, but no less so for Barghouti’s Fatah Central Committee rivals. To this day, some of his supporters swear that several prominent party members did everything in their power to sabotage the hunger strike.

Barghouti’s embarrassment led to his near-disappearance from the local political sphere, and seemed to have ended any notion of him someday succeeding Abbas.

Marwan Barghouti seen in video footage unwrapping a chocolate candy bar in his cell while ostensibly leading a hunger strike among Palestinian prisoners. (Screen capture: Israel Prisons Service)

However, various Palestinian sources say that Barghouti still insists on running come the day — either as a Fatah representative or independently. PA public opinion surveys indicate he is still a leading candidate. Israel could find that the Palestinian Authority’s president-elect is none other than its most notorious Palestinian security prisoner.

“Currently there is no point making a decision regarding Marwan’s participation in these elections,” Qadura Fares, his friend and confidant, told me. “He will declare his intentions when Abu Mazen [Abbas] issues the presidential election order. Chances are he will run, yet I don’t know if as a representative of Fatah or not. This depends on the movement and on the way it elects its candidate. If Fatah has no real democratic program before the upcoming elections, meaning real primaries, then the movement will have more than one candidate. I still think Marwan has the best chance of winning, even from jail.”

Barghouti is no longer a young, energetic leader. Although he keeps fit and exercises in prison, it’s been over 18 years since he played cops and robbers with the Shin Bet and the IDF. Fares says that there is no doubt that Barghouti — who still claims to seek a two-state solution — realizes the need to take stock, and that Palestinian politics needs to change in light of regional developments, notably the stream of Israeli agreements with Arab states, which signal the end of the PA in its current formation.

The Israeli and American sides might not want to hear this, but the Palestinian issue is not going anywhere, and it certainly isn’t going to disappear. In fact, we may face it further down the line in a more dangerous and complex form — Barghouti-style. The day after Abbas will not be anything like today, as Fares intimated during our interview:

“This whole period in Palestinian and Arab politics is unclear. My guess is that we are at the end of an era,” said Fares. “The current picture, which has held true for the past 27 years” — a reference to the Oslo Accords and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority — “will change. This calm, the Palestinian acceptance of reality, will not last. It stems from weakness and confusion. We are standing on the verge of a new period. Everything has changed around us and we’re the only ones who have not changed.”

Palestinian Authority Minister Kadoura Fares, right, and Fadwa Barghouti, the wife of jailed Palestinian Second Intifada leader Marwan Barghouti, attend a news conference in the West Bank city of Ramallah, November 26, 2004. (AP Photo/Nasser Nasser)

He added: “It’s true that there are still Palestinians who talk about two states and there is quite a bit of talk of a Palestinian state, but maybe instead of talking about a Palestinian state we should be talking about equal rights. Why do we need a state without sovereignty, without an army, a demilitarized state? What’s the point? Many Palestinians now think that it’s better to have a state called Israel but in which we have rights equal to those of Israeli citizens. I can promise you one thing: Continuing to live under occupation is not going to happen. If the choice is equal rights or establishing a Palestinian state, my feeling is that our majority would prefer equal rights.

“The agenda of the current Palestinian leadership has ended, failed,” summarized Fares. “Who caused it to fail? That is less important. The point is the failure. We don’t want fauda [chaos], and there is a lot of disappointment with Hamas. We need to work together with them and think: will establishing a Palestinian state along the 1967 borders even serve our purpose? One of our greater problems is our tendency to blame the occupation and not do any soul searching. Looking to see where we went wrong isn’t part of our culture. It is one of our wretched customs — to not conduct any soul searching and blame the Israeli occupation. Unfortunately our current leaders only repeat themselves, and no one is listening to them anymore.”

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 30th, 2020

October 30th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: