“I sleep here better than anywhere else,” a woman tells me, smiling. This confession is offered up at random, almost lazily as she walks by. My wife and I had just finished setting up our tent, and we’d been leaning against the truck discussing our game plan for the evening. All weekend, that stranger’s words would stick with me. She was right. Even in Florida’s taciturn rain and the sticky, claustrophobic heat, I always slept deeply here.

This wasn't my first time at Sawmill, the premiere gay campground in Florida—which also happens to be clothing-optional. It’s sort of in the middle of nowhere, about an hour and a half north of Tampa, with a blink-and-you-miss-it sign at the entrance. But behind the inconspicuous gate, the grounds are a gorgeous balance of promiscuity and privacy. There are acres of trails in the woods with a reputation for cruising and plenty of platonic spaces for those who don’t partake, with manicured park homes, a pool, two bars, and a nightclub called Woody’s.

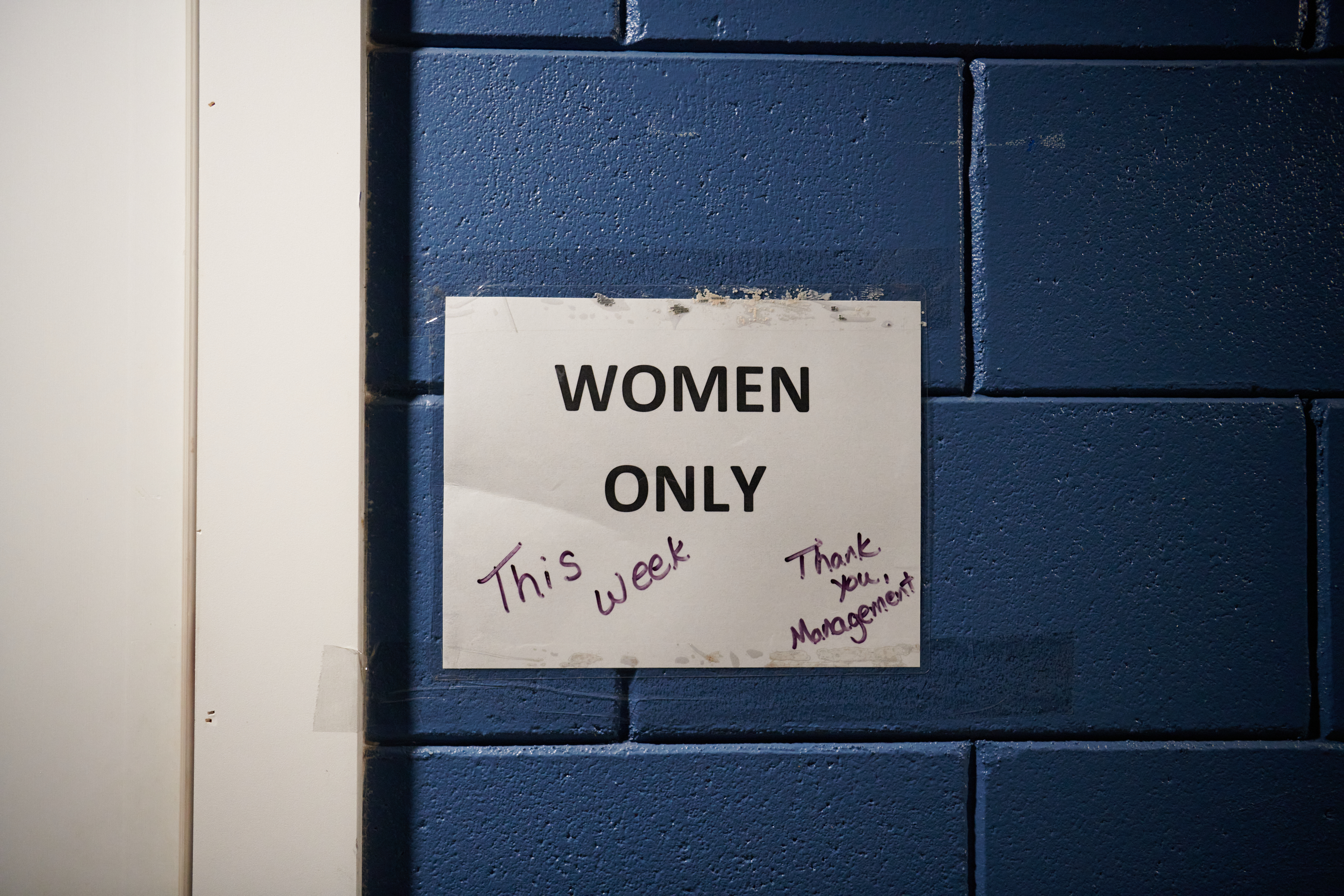

I was here for Women’s Weekend, a triannual event first launched in 1999, where Sawmill transforms from a space dominated by mostly gay men into a truly co-ed community of lesbians, queer women, trans, and non-binary folks. Still, it’s impossible not to notice an old-school vibe, with most attendees over 45 and many securely in their golden years. It’s no secret that there are generational divides between queer people, with the covert nature of some communities, the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 80s and 90s, and socioeconomic factors all playing a part. As a lesbian lucky enough to foster many relationships with older queer people—particularly butch-femme and gender non-conforming dykes—I was eager to spend time with women who have been community-building here for decades.

I wandered through a few streets of park homes—permanent, trailer-style houses owned by members of Sawmill’s co-op—and met up with Phyllis. A regular visitor since 1999 and a board member since 2019, Phyllis has shaped and been shaped by Sawmill. She and her wife Tori were married on the grounds, helped guide the community’s transition to a non-profit co-operative, and were around when Women’s Weekend was just musicians performing on flatbed trucks. We met up at the house Phyllis and Tori share as a weekend home—referred to as the Goddess Den—already packed with women and queer people eager to chat. As we crammed in on the front porch, the rain sputtered on and off.

“It's about feeling connected. You know, being with, not necessarily your blood family, but being with others,” says Phyllis. The early founders “had the vision of a place for people in the southern states and Florida to have a safe place for gay people.” She says most people hear about Sawmill through word-of-mouth and come for a specific event—like Pup, Leather, 70s Bathhouse, Latin, or Women’s weekends—before ending up life-long visitors. With this lineup, Phyllis says it’s a common misconception that Sawmill is for men only, but it’s always been fully open to folks of all genders. Still, like with all communities, there have been periods of tension, particularly between men and women.

“The guys would just pack up and leave for the women’s festivals,” Tori tells me. Some of this sentiment lingers; when my wife solo camped in 2016, the reception was chilly. A man approached her and said simply, “We don’t like women here.” But, Phyllis adds, they have a zero-tolerance policy for intimidation, harassment, and disrespect. It took a while to get here, she says, but “the [men] accept us wholeheartedly.” There’s a long history of women living at Sawmill, as well, including a pair of lesbian former nuns who stayed in the community well into their 80s.

As Phyllis talks, I notice my wife is crying. There’s a mix of pleasure and pain in hearing these stories of queer love and reconciliation—and there's a real need for them. Just look at the million TikToks out there from Gen Z-age queer people posting about their hunger for friends, peers, and mentorships—seeking any window, no matter how small, to look through and see their own histories. At the same time, there has been a push from elders (AKA elderqueers) to share their stories on social, give advice, and offer mentorship to their younger counterparts. This sort of online support base is deeply meaningful, especially for those who live in rural places, live with hostile family members, or simply don’t have access to other out queer people who can help guide, or even just witness, them. Still, it’s not enough.

Being in the Goddess Den with so many women was a singular experience, one that couldn’t be repeated online. It was the difference between reading Leslie Feinburg’s Stone Butch Blues and actually sitting across from a stone butch, recounting her griefs and joys in real time. There’s something particular about seeing a different, older version of yourself sitting across from you, running their fingers through their hair, looking at their partner, the sound of many voices raised in laughter. It looks like a future, a possibility, knowing that someone made it to the other side of struggle—which for many queer people is not a given.

“When we were younger, there wasn’t anything,” says Maggie, a 50-something butch sitting next to her wife, Annette. Right off the bat, Maggie reminds me of every woman I’ve ever pined over: short hair, big build, easy smile. A Miami local, Maggie says she did have access to some gay nightclubs, but she could never have imagined an opportunity to sit, talk, and relax around so many other lesbians. “The friends we've made here [are] lifetime friends. I am with family,” she says. I watch as Annette leans into her, nodding.

But not everyone who finds Sawmill was seeking it out, exactly. In 2020, Brooke and Kiwi were driving through Florida from Michigan in a Honda CRV hitched with a teardrop trailer. It was their one-year anniversary, Brooke, 30, tells me, and they were sick of spending nights in random parking lots. “We could not, for the life of us, find a place to sleep,” says Kiwi, 29. Scrolling through Google, Brooke found Sawmill last minute, so they rolled up for the night without any clue what Sawmill or Women’s Weekend was.

“People ended up paying for our site so we could stay for Women’s Weekend,” says Kiwi. After a week, Kiwi and Brooke still had no money, and they didn’t have anywhere else to go. So, Tori and Phyllis asked them to move into their full-time residence in Tampa Bay until they could finish building out their live-in van and tuck enough money away. “They had known us for maybe two days,” Kiwi says. They ended up staying with Phyllis and Tori for 9 months.

That night, I went to sleep thinking about how lucky I’d felt at the Goddess Den, surrounded by women in love with each other and the families they’d built. At a time when queer and trans people (especially, it should be noted, in Florida) face continued political and personal violence, the type of bonds, care, and joy happening at Sawmill reminds me of the trait every generation of queer people have in common: persistence.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 4th, 2023

March 4th, 2023  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: