April 18, 2021 by Ben Cohen

Read on for article

In the series “Letters to a German Friend,” written clandestinely during the Nazi occupation of France, the celebrated French writer and resistance figure Albert Camus conducted a debate with an imaginary German correspondent who believed fervently that any act was justified if it contributed to a greater destiny for his nation.

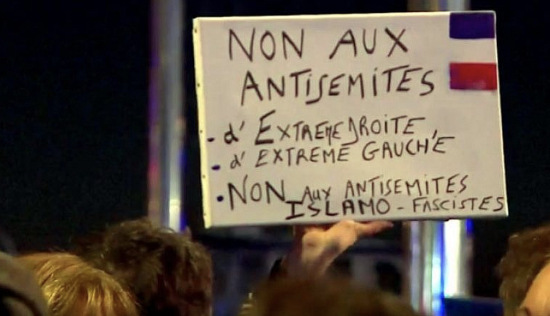

Thousands joined rallies in Paris and across France on Feb. 19, 2019, to oppose a rising wave of anti-Semitism in the country. Credit: Screenshot.

“I loved you then, but at that point we diverged,” Camus wrote. “… There are means that cannot be excused. And I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice.”

Nearly 80 years after the liberation of Paris, would Camus be able to love both his country, France, and the idea of justice without perceiving a conflict between the two? Certainly, a philosopher of his pedigree would be anxious to establish whether justice was universally applied to all citizens, regardless of confession or origin, as should be the case in any democratic republic. In doing so, he or she might notice that for most of the present century, a steady stream of Jewish victims of anti-Semitic violence has received partial justice at best—or no justice at worst—from the French legal system. It is a record that shames a country whose ethic is built upon the triangle of “liberty, equality and fraternity.”

The list of French Jews who died because they were Jews includes Sebastien Salem, a DJ murdered in 2003 by a Muslim childhood friend; Ilan Halimi, a mobile-phone salesman kidnapped, tortured and murdered by an anti-Semitic criminal gang in 2006; Sarah Halimi (no relation to Ilan), a child-development expert beaten to death and thrown out of her apartment window by a Muslim neighbor in 2017; and Mireille Knoll, a Holocaust survivor who was robbed and then burned to death in her own home by two youths, one of whom she had known since his childhood, in 2018. Then there are the victims of the Islamist terrorist attacks on a Jewish school in Toulouse in 2012 and a kosher market in Paris in 2015—eight in all, among them three young children. All those lives were snuffed out in the name of Jew-hatred amid a broader context of soaring anti-Semitism, and still the French judiciary acts as though there are far more important problems to worry about.

Last week, the insult to French Jews escalated to new heights when the Court of Cassation, France’s highest appeal court, ruled that Sarah Halimi’s accused murderer, Kobili Traore, would not face a criminal trial for his bestial act. In the early hours of April 4, 2017, Traore, who lived in the same Paris public housing project as Halimi, broke into his victim’s apartment. Once inside, he kicked and punched her relentlessly while bellowing the word “Shaitan” (Arabic for “Satan”). Traore ended the ordeal by hurling Halimi’s broken body out of the window of her third-floor apartment to her death.

So began a distressing, unsettling four-year saga of courtroom battles and media clashes that ended, with cruel finality, with the Cassation Court dismissing the Halimi family’s quest for justice. Traore will not face trial because a group of psychiatrists appointed by the court determined that his intake of marijuana around the time of the killing had wiped out his “discernment,” or self-awareness. According to the French penal code, this mental blip means that he cannot be held legally responsible for Halimi’s murder.

This has been the position of the French courts from the beginning, leading outraged observers to ask whether imbibing drugs or alcohol will now be regarded as a mitigating circumstance in drunk-driving accidents or brawls in pubs that result in a dead body. According to Article 122-1 of the French penal code, a “person is not criminally liable who, when the act was committed, was suffering from a psychological or neuropsychological disorder which destroyed his discernment or his ability to control his actions.” The same article also makes clear—and this is what covers the roadside accidents and bar-room fights—that a “person who, at the time he acted, was suffering from a psychological or neuropsychological disorder which reduced his discernment or impeded his ability to control his actions, remains punishable.”

The court decided that Traore fell into the first category, even as it recognized that his alleged “mental illness” was the result of his voluntarily smoking large amounts of marijuana on a daily basis. “[H]is mental illness began on April 2, 2017, and peaked on the night of April 3 to 4, 2017, in what psychiatric experts unanimously described as a ‘delusional puff,’ ” the Cassation Court’s decision explained. The court therefore believes—and wants us to believe—that Traore took one too many drags on a marijuana joint, resulting in his loss of all sense of self and all sense of control. For about 48 hours, we are told, he was—to quote the penal code again—“suffering from a psychological or neuropsychological disorder which destroyed his discernment or his ability to control his actions” (my emphasis).

In case that description wasn’t clear enough, the court’s statement added: “The judges add that the fact that this delusional puff is of exotoxic origin and due to the regular consumption of cannabis, does not prevent the recognition of the existence of a psychic or neuropsychic disorder having abolished his discernment or the control of his acts, since nothing in the information file indicates that the consumption of cannabis by the person concerned was carried out with the awareness that this use of narcotics could lead to such an event.” In other words, the fact that Traore is responsible for his supposed mental collapse because he smoked marijuana doesn’t mean that he is responsible for the murder he executed during that collapse. Case dismissed.

Remember, under the same article of the French penal code, the judges had the discretion to recognize that even if Traore was stoned out of his mind, he was still responsible, and punishable for, the slaying of Sarah Halimi. They chose not to interpret their own law in that manner.

Why? That is a question to be asked again and again, and those of us who have covered this case from the beginning will continue to probe for answers. But set against the background of French Jewish history over the last century or so—from the Alfred Dreyfus trial through the Holocaust and into a post-war cauldron of anti-Semitism from the far-right and the extreme left—the fundamental answer suggests itself. France is a land of systemic anti-Semitism, where Jews, if they are victimized as Jews, can expect to relive their traumas as they seek justice in the courts.

“Man’s greatness … lies in his decision to be stronger than his condition,” Camus wrote in a different wartime article. “And if his condition is unjust, he has only one way of overcoming it, which is to be just himself.” In the case of Sarah Halimi, France has manifestly failed that moral test.

Ben Cohen is a New York City-based journalist and author who writes a weekly column on Jewish and international affairs for JNS.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 18th, 2021

April 18th, 2021  FAKE NEWS for the Zionist agenda

FAKE NEWS for the Zionist agenda  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: