Above photo: People waiting in line to vote. El 19 Digital.

Masaya, Nicaragua – Official results from Nicaragua’s elections on November 7 showed Daniel Ortega re-elected as president with 75% of the vote. On the same day, President Joe Biden dismissed the ballot as a “pantomime election” and within 48 hours the Organization of American States (OAS) had produced a 16-page report setting out its criticisms. It demanded the annulment of the elections and the holding of new ones, disregarding international and OAS rules that require respect for the sovereignty of nations. Yet it contained no evidence of problems on election day itself that would substantiate its objections. Nevertheless, local and international media were quick to endorse the accusations that widespread fraud had taken place.

This article tries to identify the basis of these accusations, examines the evidence offered to support them and shows why, in practice, the massive fraud being alleged was very unlikely to have happened.

The electoral process – in brief

Before addressing the allegations, let’s look briefly at the process. Nicaragua has developed an electoral system which is probably one of the most secure and tamper-proof in Latin America, with multiple checks on the identity of voters and the validity of ballots. There were 13,459 polling stations covering up to 400 voters each, in an operation involving about 245,000 volunteers and officials across the country.

Jill Clark-Gollub has described at COHA how this worked on the day. Briefly, each voter must:

- Go to vote in person (there are no postal or proxy votes).

- Have a valid identity card that carries their photo and signature.

- Be entered on the electoral register for the polling station, where their name is ticked off (in most cases this is computerized).

- Have their ID checked against a print-out which has a small version of their photo and their signature: they sign on top of this to certify that they are going to use their vote.

- Be given a ballot paper, which is stamped and initialed by an official before being handed over (see photo).

- Make their vote in secret and put the paper in a ballot box.

- Retrieve their ID card, and have their right thumb marked with indelible ink to show they have voted.

Each polling station has representatives of the political parties (in the U.S. they would be called party poll watchers). The poll watchers are there from the time the polling station opens until it closes – they watch everything – and at the end of the day they also sign the record of the polling. The numbers of votes, in total and for each party, are counted when polling closes and the results certified by the party representatives. The ballot boxes are then taken to a central counting center, accompanied by police or army officers, with each box tagged to ensure that it cannot be tampered with or replaced. The count at the center must match the count in the polling station, and this is again monitored by the poll watchers. Counting starts as the boxes are received and continues non-stop until every vote has been dealt with.

Despite these precautions, the international media and the opposition groups who were not represented on the ballot have not hesitated to condemn the process. For example, William Robinson, writing for NACLA, claims there was “a total absence of safeguards against fraud.” The different critics make one or more of these accusations:

- That opponents who would have entered the election were prevented from running, and their participation would have secured Ortega’s defeat.

- That the size of the registered electorate was manipulated in the government’s favor.

- That polls showed that the government was deeply unpopular, therefore the election result must have been a fake.

- That the high proportion of spoiled ballots was a concerted “protest vote.”

- That, after the opposition called on its supporters to abstain, most people did so.

- That the government “added” one million votes in its favor.

Here we show the plentiful evidence to contest these allegations.

- Potential election winners were excluded

“After methodically choking off competition and dissent, Mr. Ortega has all but ensured his victory in presidential elections on Sunday, representing a turn toward an openly dictatorial model that could set an example for other leaders across Latin America.” (New York Times, November 7)

Most of the international media ignored who was on the ballot and focused instead on the arrests of opposition figures earlier this year, which allegedly removed all effective opposition. The reasons for the arrests have been dealt with by Yader Lanuza and Peter Bolton, but briefly they were for violations of laws relating to improper use of money sent to non-profit organizations, receiving money from a foreign power intended to undermine the Nicaraguan state and influence its elections, and seeking international sanctions against Nicaragua.

But in fact, the ballot included five candidates challenging Daniel Ortega for the presidency (see photo). The NYT said, wrongly, that all “are little-known members of parties aligned with his Sandinista government”). However, these are historic parties – two of them (the PLC and PLI) had formed governments in the years 1990-2006, and in the case of the PLC in particular enjoy strong traditional support. The Sandinista front itself won as part of an alliance of nine legal parties.

Regardless of the arguments about the validity of the arrests, there is no plausible scenario where, if one of those arrested had been eligible to stand, they would have amassed sufficient votes to win. Not only was this unlikely because of the math (see below), but also because not a single one of those arrested had then been chosen as a candidate, the newer opposition parties that might have chosen them were unable to agree on how to stand or who to choose, and none had any program other than vague calls to re-establish “democracy” and “release political prisoners.”

Nevertheless, according to a CID-Gallup poll in October, the most popular opposition figure, Juan Sebastián Chamorro, had 63% popular support. Let us take a look at a possible scenario, assuming he had been allowed to stand for one of the newer parties:

- Suppose that, as a consequence of his participation, electoral turnout had increased, reaching its highest in recent elections (73.9% in 2011). This would have produced a total of 3,309,000 valid votes, an increase of around 400,000.

- Assume for the moment that the Ortega vote remained the same, and that Chamorro had gained all the non-Ortega votes, including all those won by the other opposition parties:

Chamorro’s total vote would have been about 1,200,000.

- However, it would still have fallen short of Ortega’s by more than 800,000 votes.

- So to have won, Chamorro would have needed to persuade over a fifth of Ortega voters (almost 440,000) to swap sides, despite the deep hostility towards the Chamorros shown by most Sandinistas.

In practice, of course, it was highly unlikely that Chamorro would have stood as the sole opposition candidate, not only because he had rivals from the “traditional” opposition parties such as the PLC, but also because even as the election approached the newer opposition was divided into different groups backing different potential candidates. A divided opposition would have had an even smaller chance of winning.

- The size of the registered electorate was manipulated

“In order to put Ortega’s electoral victory cards on the table, the CSE [Electoral Council] proceeded to increase the registration of the number of people eligible to vote.” (Confidencial)

“…experts estimated that this year’s roll should be at least 5.5 million.” (La Prensa)

The second accusation is that the electoral register of 4,478,334 potential voters was manipulated in the government’s favor, although critics can’t agree on whether the register was inflated or deliberately shrunk.

Opposition website Confidencial argued that the growth since 2016 of around 600,000 in the total numbers eligible to vote was implausible, and it was also implausible that 97% of those eligible were actually registered. However, when opposition newspaper La Prensa assessed the size of the registered electorate, their complaint was that it was too small. According to their analysis, the register should have had approximately 5.5 million voters, so the government was presumably intent on cutting out voters in areas where it has low support.

Either accusation is easily answered. The natural growth in the tranche of the population aged over 16 (those eligible to vote) accounts for about half the increase in the size of the register. Both Confidencial and La Prensa deliberately ignore the huge improvement in the registry of citizenship since 2016, so that almost all the adult population now have identity cards, needed for many everyday transactions, and which automatically enter the holder on the electoral register. Rather than being implausible that 97% of citizens are registered, as Confidencial claimed, it is an intended outcome of the modernized system, which aims for 100% registration. This means that the register has gained in accuracy as the campaign to extend ID cards to the whole population nears its goal.

- The government is deeply unpopular, contradicting the election result

“A recent poll showed that 78 percent of Nicaraguans see the possible re-election of Mr. Ortega as illegitimate and that just 9 percent support the governing party.” (New York Times, November 7)

The official election results give the ruling Sandinista Front 71.67% of the votes, if spoiled ballots are included (75.87% if they are excluded). This is similar to the 72.44% vote share obtained in the 2016 election. The second party, the PLC, gained 14% of the vote, similar to its 15% share in 2016.

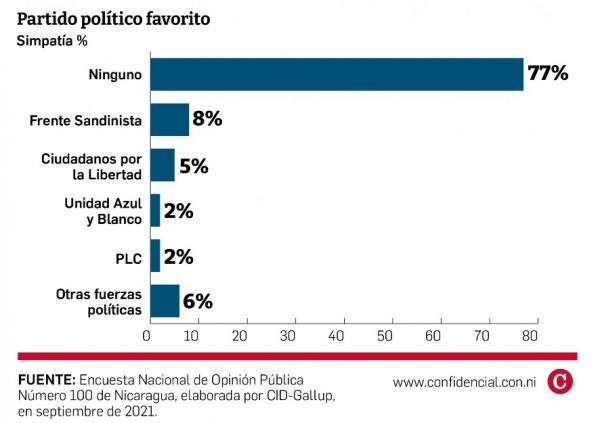

Opinion polls cited by the international media and the opposition purport to tell an entirely different story. According to a poll by Costa Rican firm CID Gallup (not part of the internationally known Gallup organization), in September-October only 19% of adults would have voted for Ortega had the election been held then, while 65% would support an opposition candidate. In a slightly later CID Gallup survey, paid for by Confidencial, 76% of adults questioned said that Ortega’s re-election would be “illegitimate;” his party’s level of support had by then fallen to only 9% (i.e. about 400,000 potential votes).

The CID Gallup poll’s findings on levels of support for different political parties are rather baffling. While some 68% of those questioned said they were likely to vote, the vast majority (77%) claimed to favor no particular party. Levels of support for individual parties were therefore tiny: the Sandinista Front was judged to have most support, but favored by only 8% of voters, while others had even smaller followings. Those questioned had the option of choosing one of the supposedly popular parties that were prevented from running, but these also received miniscule support: 5% for the CxL (Ciudadanos por la Libertad) and just 2% for the UNAB (Unidad Azul y Blanco). Had these parties been allowed to take part in the election, their candidates might have been one of the supposedly popular figures arrested beforehand, such as Juan Sebastián Chamorro.

None of the international media who cite the CID Gallup poll question the credibility and consistency of these findings. Nor do they ever mention the more regular and more extensive opinion polls conducted by Nicaragua-based M&R Consultores, which gave a much different picture (see chart). Their results show Daniel Ortega with a 70% share of the vote, a percentage which had increased steadily as the polls approached. M&R claims its surveys are more rigorous, covering more of the country, with 4,282 face-to-face interviews while CID Gallup relies on cell phone calls for its 1,200 responses.

Adding to the implausibility of the CID Gallup poll findings is the fact that some 2.1 million Nicaraguans, slightly under half the adult population, are card-carrying members (militantes) of the Sandinista Front, following a membership drive over the last two years. That less than a quarter of these would vote for the party of which they are members seems, at best, highly unlikely. CID Gallup’s findings would also of course imply that no one who was not a party member would support the government, which is also highly unlikely. Nevertheless, even on election day, opposition leaders such as Kitty Monterrey (herself prevented from standing) hubristically claimed that more than 90% of voters would cast their ballot against Ortega.

- Invalid votes “won”

“Null votes confirm Daniel Ortega’s re-election farce” (headline in El Faro)

Because the CID Gallup poll appeared to show a high proportion of voters having no party allegiance, there have been a couple of attempts to argue that a protest vote, ie. people spoiling their ballots, “won” the election. There is some very limited truth in this, in that the proportion of ballots spoiled was notably higher than usual, at about 5%, rather than a more typical 1-2%, and these additional spoiled ballots may have represented a “protest vote.”

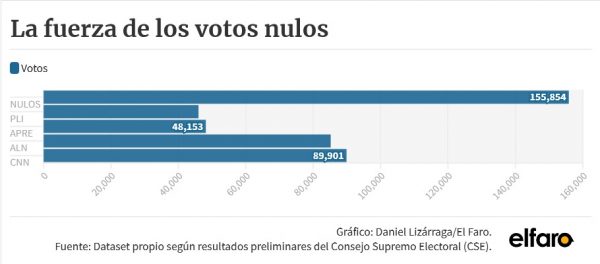

The El Salvadoran website El Faro, which regularly gives a platform to Nicaragua’s opposition, tried to show “the strength of the invalid votes.” After claiming that abstentions reflected a “third force,” El Faro published a graphic (below) showing how spoiled ballots “outvoted” the opposition parties.

However, a proper comparison between the percentage of invalid votes and those gained by the different parties puts this in perspective (see pie chart). As can be seen, the partial graphic displayed by El Faro gives the votos nulos far more importance than they merit: yes, there were more spoilt ballots than votes for some of the minor parties, but the proportion was well below that gained by the PLC and, of course, by the FSLN. The 161,687 spoiled votes hardly show the electoral “farce,” depicted by El Faro. They were presumably hoping that their readers, glancing at the story and the graphic, would get the impression that the protest vote had “won.” Inadvertently, El Faro’s story also undermines the accusation (see below) that abstentions “won.” If it were really true that only 850,000 people voted, as the abstention camp claims, the 161,687 spoiled votes would have formed an improbably high proportion (19%) of the total.

Another approach to exaggerating the importance of votos nulos was pursued by La Prensa. On each ballot paper there were four voting options so, according to La Prensa, the protest vote was four times the actual total of invalid votes, therefore reaching 666,866, rather than 161,687. This suggests a degree of desperation on La Prensa’s part in its search for ways to discredit the election.

- Abstentions “won”

“Once polls opened early on Sunday morning, some polling stations had lines as Nicaraguans turned out to cast their ballots. But as the day progressed, many of the stations were largely empty. The streets of the capital, Managua, were also quiet, with little to show that a significant election was underway.” (New York Times, November 7)

Official results show 66% of registered voters took part in the election, a level within the range (61-74%) of the previous three elections. It is also a level of participation similar to the last elections in the U.S. and the U.K. (which were both higher than normal) and in the middle of the range of participation in other countries’ recent elections.

The international media largely ignore this and cite the opposition website Urnas Abiertas (“Open ballot boxes”) which claims that 81.5% of voters abstained (see graphic). In other words, while officially 2,921,430 voted (including spoiled ballots), Urnas Abiertas say the real figure was more like 850,000.

Urnas Abiertas do not, however, provide any evidence of it other than their claimed survey of attendance at a sample of polling stations, which is only briefly described in a few lines of their four-page report. It offers no technical details of their work or examples of polling stations which they surveyed. Described as “independent” by right-wing newspaper La Prensa, Ben Norton shows how Urnas Abiertas is an obscure organization with few followers and is operated by known opposition supporters.

Various opposition media, such as 100% Noticias, published pictures of “empty streets” or empty polling stations” on November 7, presumably as evidence that the opposition’s campaign to boycott the elections had been successful. In typical fashion, international media picked up the story and, of course, opposition supporters were busy phoning their contacts in the U.S. and elsewhere to give the story credence.

The local media had conveniently forgotten a story they covered earlier in the year. In July, the electoral authorities published a provisional electoral register, and invited voters to verify their entries and check they were allocated to the correct polling station. This exercise was massively supported, by 2.82 million voters out of a possible 4.34 million then registered (the registered total has since increased by about 130,000 as entries were updated). The opposition media, intent on showing supposed anomalies in this process, inadvertently also showed the scale of the response it received from the public, with videos of queues of people waiting to verify their vote. The likelihood is that, having turned up at the polling station to check their right to vote, people turned up again on November 7 to use it, and the similarity in numbers who did both confirms that this was the case.

The photos of “empty streets” and “empty polling stations” were in any case highly misleading: it is easy to take such shots, especially on a Sunday when businesses and schools are closed, and especially at the hottest time of day. Furthermore, a simple calculation of the likely attendance at each polling station, open for 11 hours with (on average) 333 potential voters and 216 who actually voted, shows that roughly 20 people an hour would have passed through each one. Given that each person needs only a few minutes to vote, it is obvious why queues occurred only when groups of voters arrived simultaneously.

- The Sandinistas added at least one million votes

“To the amount of votes reported in favor of Ortega, the CSE [Electoral Council] fraud added about one million extra votes.” (Confidencial)

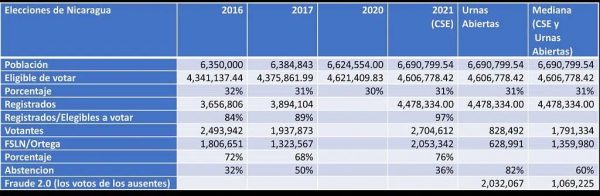

Table comparing the 2021 election results with previous elections and with alternative analyses of the 2021 results by Urnas Abiertas and Confidencial. Note that the 2017 elections were for municipalities, where turnout was lower and people were more likely to vote for diverse parties.

Critics argue that massive abstentions mean that fake votes were created, but they can’t agree how many. Confidencial suggests that it was 1,069,225, while the implication of the “survey” by Urnas Abiertas is that false votes totaled 2,032,067. Confidencial helpfully produced a table (see above) comparing the official (CSE) result with its own and those from Urnas Abiertas, adding for comparison the official results from previous elections. (As with many of the other opposition graphics, one suspects that spurious accuracy is given to their data to make them appear more authentic.)

An attempt was made to substantiate the fraud accusation when a false image of a “manipulated” electoral scrutiny form was circulated by the opposition ahead of the election, suggesting that exaggerated vote totals were being prepared in readiness for November 7. It proved to be a copy of a sample document circulated openly in its briefing materials by the Electoral Council.

In practice, the obstacles to the organization of this scale of fraud can be seen from the brief description already given of how votes were verified on polling day. Clearly, creating 1 to 2 million false votes would require a large proportion of the 13,459 polling stations and 245,000 officials to be engaged in the process. This is because the fraud would have to start at the points where votes were cast, because if the false votes had been created centrally the discrepancy with local voting tallies would be blatantly obvious.

Is it really feasible that every polling station (or most of them) created up to 200 false votes from entries on their register using blank ballot forms, stamped as authorized by officials, at the risk that real people with those votes would turn up and find they had already “voted”? Or, if it was done after polls closed, would there have been no complaint from poll watchers from rival parties, and would none of the 245,000 people involved have leaked the truth about what really happened, in a country as chismoso (gossipy) as Nicaragua? The whole notion is absurd.

As I write this, it is one week since the election took place. I have been unable to find any evidence of actual fraud (as opposed to speculation about fraud) in any of the main media which support the main opposition groups.

The real response to the accusations

While this article has exposed the implausibility of the various accusations, the real response to them was the scenes on the streets on election day and during the celebrations when the results were announced officially on November 8. While some of the media portrayed empty streets and deserted polling stations, there were hundreds of photos (see below, from Bilwí) which showed the opposite.

Many international representatives who acted as election “accompaniers” confirm that the polls were well attended and that people talked freely and often enthusiastically about the process, even those opposed to the government (see reports by, for example, Roger Harris, Rick Sterling and Margaret Kimberley).

Living in Masaya, which had been a stronghold of opposition support in the violence of 2018, I was amazed by the response to the president’s speech after the result was announced: tens of thousands of people poured onto the streets on Monday November 8, especially in poorer barrios, waving Sandinista flags and even holding up portraits of Daniel Ortega. While clearly a minority opposed his re-election, it was equally clear that the majority supported it.

Published originally at the Council of Hemispheric Affairs, COHA.org, on November 16, 2021. Read the original publication.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 18th, 2021

November 18th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: