Icelanders believe in elves. They refuse to begin major construction projects unless they consult with elves first. They lobby their politicians on behalf of elf colonies. They run “elf schools” and “elf tours”. Elves in Iceland are everywhere and all around.

Reality Check

Few things about the Icelandic nation are as misrepresented as its ancient belief in the hidden people. Somehow this idea that modern Icelanders believe firmly in the existence of elves gained a bit of traction in the international media a few years back, and the idea snowballed until it seemed that every other media outlet had a “those kooky Icelanders and their elves” story. Yet the elf belief has much deeper and more significant roots that those sensationalized media stories illustrate.

We Icelanders are very much aware of our hidden people legacy, but today the elf belief is mostly a non-entity in our daily lives. That being said, occasionally there will be a story of some incident in rural areas where, say, elves are blamed for the breakdown of construction equipment when land is being bulldozed—though it is hard to know whether or not such remarks are in jest.

Ancient Tales of Hidden People

There is no doubt, though, that these stories served an important purpose for our ancestors. Our old folk tales speak of álfar and huldufólk – two terms that mean, respectively, “elves” and “hidden people”, and are used more or less interchangeably. They refer to the same sort of beings— (hidden) people who lived in a parallel world to the mortals, yet were invisible to them.

For people outside of Iceland, the term “elves” probably conjures up a very different image than it does for Icelanders who hear about “álfar”—some variation of a diminutive being with pointy ears, who may or may not be green.

Scuplture of “Korrigan”, small elf of the Celtic forests. ( CC BY 2.0 )

The álfar of Icelandic folklore, however, were quite a different apparition: tall, regal beings, dressed in luxurious clothing, whose homes were opulent, filled with tapestries and ornaments of gold and silver. They were akin to Tolkien’s elves of Middle Earth, though without the pointed ears.

They also held a great deal of power. Hidden people frequently appeared to humans in dreams, often because they needed help. Many stories involved hidden-women in labor who had to have a mortal woman assist them in giving birth. If the mortal woman did as the hidden person (often the husband of the hidden woman in labor) requested, her life inevitably changed for the better. Her crops excelled, her children thrived, and good fortune permeated all aspects of her life.

The álfar of Icelandic folklore were tall, regal beings, dressed in luxurious clothing. ( Boris Ryaposov /Adobe Stock)

If, however, she refused to help the hidden person, her life took a turn for the worse and she often wound up destitute. In other words, the hidden people had the power to make or break a person’s destiny.

Escape to a Land of Abundance and Safety

Many scholars now believe that the belief in hidden people served a significant psychological purpose for the Icelanders in centuries past, acting as an anti-depressant. Iceland was truly on the edge of the inhabitable world in the days before electricity and central heating. The Icelanders were an oppressed and downtrodden colony, living in turf houses that were dark, dank, and infested with bugs, and they were frequently starving.

Infant mortality was high, disease rampant, poverty pervasive, and the landscape and climate harsh and unforgiving. Given these abject conditions, people escaped into a fantasy world, a parallel universe that was very close to their own, in which people very much like themselves lived lives of abundance, prosperity and relative ease. Everything was better in the hidden world – even their sheep were fatter and their crops more bountiful than those of the humans.

Painting of Icelandic family in kvöldvaka, by August Schiøtt (1823 – 1895) ( Image Source )

Yet that was not the only way in which the hidden people stories served to ease the lives and emotional trials of the Icelanders. They also helped them deal with loss and grief. Many hidden people stories involve them abducting the children of mortals and taking them to the hidden world, where they raised them well. These stories, it is now believed, bely a tragic reality.

Many children in the Iceland of old went missing. Perhaps their parents did not keep watch over them—after all, people worked up to 18 hours a day in the summer, trying to get the most out of the short season, and children were left more or less to their own devices. Or the children would themselves be working, often alone, as they were sometimes put to work as early as the age of five. Whatever the cause, they often went missing, and given Iceland’s dangerous landscape it is not hard to imagine that they frequently met with accidents: falling into a river, or off a cliff, or into a deep lava crevice.

Laufskalavarda lava ridge and stone cairns, Iceland. (salajean /Adobe Stock)

How does a parent grieve for a child when there is no privacy, where one lives with up to ten people in a room about four yards wide and ten yards long? Perhaps they tell themselves that the child has gone to live in the hidden world, where he or she will be well taken care of. The hidden people tales were likely a way for people to process their grief.

The Gentle Men

Another motif in hidden people stories concerns the romantic and sexual involvement of mortal women and hidden men, who were called ljúflingar, literally: “gentle men”. In these stories, the woman was very often working in the so-called mountain dairy, or sel in Icelandic, a rudimentary structure located near the mountain pastures, a considerable distance from the farm.

This is where the sheep were kept during the summer, and female laborers were often stationed there, sometimes alone, sometimes with a child who watched over the sheep in the pastures, and sometimes with more people, depending on the size of the farm. The woman would be responsible for milking the ewes daily and making butter and skyr, an Icelandic dairy product, similar to yogurt.

Turf house with a wooden gafli in Iceland. ( CC BY 2.0 )

In the stories, the women often became romantically involved with hidden men, and fell pregnant. The hidden man would be very attentive to the woman during her pregnancy, would assist her in childbirth, and afterwards would take the child away to raise it in the hidden world. As an added twist, the hidden man was never able to forget the mortal woman, nor she him, making for a tortured, unrequited romance.

Scholars today interpret these stories in a couple of different ways. One, it is possible that they were the Harlequin Romances of the time, serving as fantasies for lonely women who would probably not get married, since the authorities of the times placed tyrannical restrictions on who could marry , and regular laborers were at a decided disadvantage. So again, the stories of the lovers from the hidden world helped women escape the severity of their own realities.

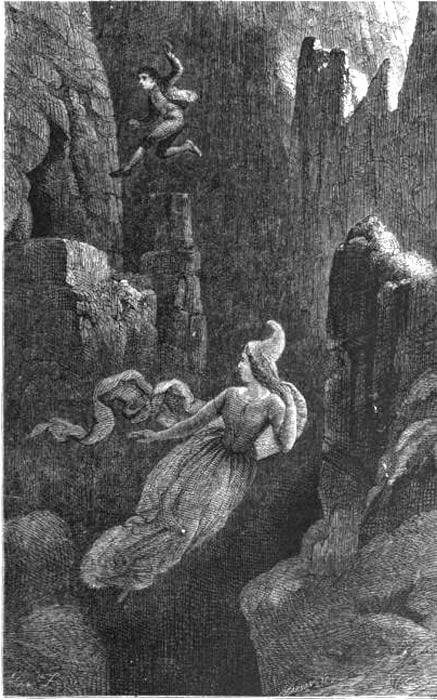

An engraving showing a man jumping after a woman (an elf) into a precipice. It is an illustration to the Icelandic legend of Hildur, the Queen of the Elves. ( Public Domain )

Another explanation, however, is more sinister. Women who worked the sel were often the victims of sexual abuse, either at the hands of their employers or by men from nearby farms. Icelandic law at the time imposed harsh penalties for having children out of wedlock, and so, the stories of the ljúflingar might have been a way to justify an unwanted pregnancy. Even more tragically, the notion that the child was carried away by the hidden man might have been a cover-up for infanticide, which sadly was prevalent in those days, given the cruel repercussions attached to illegitimate births.

The couple of examples outlined above have little in common with the sensationalized “Icelanders believe in elves” stories in the media or the Icelandic tourism industry. In fact, that presentation rather trivializes a tragic and profound reality, completely bypassing the glimpse it provides into the rich cultural history of the Icelandic nation.

Elf houses in Iceland. ( NJ /Adobe Stock)

Alda Sigmundsdóttir is an Icelandic writer and journalist. She is the author of ‘The Little Book of the Hidden People’, and ‘The Little Book of the Icelanders in the Old Days’. You can find her on Facebook or Twitter.

—

Top Image: Haunting and beautiful Middle-Earth-like elves by artist (Araniart/ CC BY 3.0 )

Updated on July 21, 2021.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

July 21st, 2021

July 21st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: