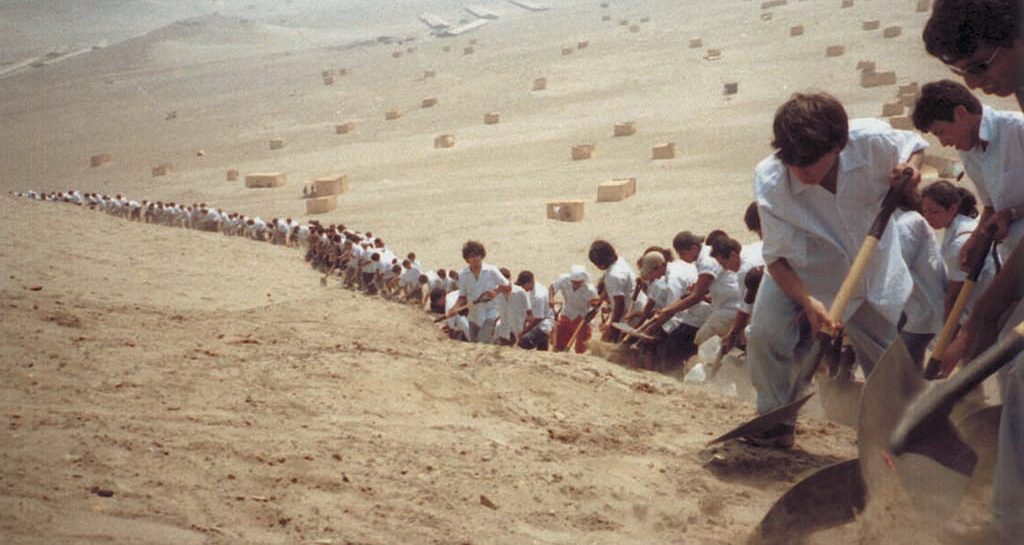

Above photo: Francis Alÿs, When Faith Moves Mountains, 2002. Francis Alÿs Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

Our era will be remembered for the triumphant march of authoritarianism in whose wake the vast majority of humanity have experienced unnecessary hardship and the planet’s ecosystem has suffered avoidable climate destruction.

For a brief period – a period the British historian Eric Hobsbawm described as “the short 20th century” – establishment forces were united in dealing with challenges to their authority. It was a rare period in which the establishment had to face a variety of progressives, all seeking to change the world: social democrats, communists, Read more about these ideas here ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-infocard-contents-bf0472f7-0b32-466f-a15c-0debc73119a6″ data-initialized-as=”a”>self-management experiments, national liberation movements in Africa and Asia, the early, radical, ecologists etc.

I grew up in mid-1960s Greece, governed by a right-wing dictatorship that was instigated by the United States under Lyndon Johnson (whose administration was one of the most progressive domestically, but which nonetheless did not hesitate to prop up fascists in Greece or carpet-bomb Vietnam). The fear and loathing of right-wing populism that can be found today plastered on every page of the New York Times was simply absent back then.

Things changed after 2008, the year the western financial system imploded. Following Read more in Ann Pettifor's piece on the global financial system ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-sidenote-contents-5e090d38-833d-4a10-9b08-61338e1828b1″ data-initialized-as=”a”>25 years of financialisation, under the ideological cloak of neoliberalism, global capitalism had Read more here ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-infocard-contents-df9bd4e7-9043-4941-8f01-7afd99f008a8″ data-initialized-as=”a”>a 1929-like spasm that nearly brought it to its knees. The immediate reaction to this crisis, intended to prop up financial institutions and markets, was to turn on the central banks’ printing presses, and to transfer bank losses to the working and middle classes via so-called “bailouts”.

This combination of socialism for the few and stringent austerity for the masses did two things. First, it depressed real investment globally, as firms could see that the masses had little to spend on new goods and services, producing discontent among the many while the very few received huge doses of “liquidity”.

Secondly, it gave rise initially to progressive uprisings – from the Indignados in Spain and the Aganaktismeni in Greece to Occupy Wall Street and various left-wing forces in Latin America. These movements, however, were relatively short-lived, and they were efficiently dealt with either by the establishment directly ( Read more here ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-infocard-contents-cb866901-aa6a-4771-9c18-e4ecf5ef5d4b” data-initialized-as=”a”>the crushing of the Greek Spring in 2015, for example) or indirectly (leftist Latin American governments fading as Chinese demand for their exports collapsed).

As progressive causes were snuffed out one by one, the discontent of the masses had to find a political expression. Mimicking the rise of Mussolini in Italy, who promised to look after the weakest and to make them feel proud to be Italian again, we’ve witnessed the rise of, what we can call, the Nationalist International, most clearly expressed in the rightist arguments fuelling Great-Britain’s exit from the European Union and the election successes of right-wing nationalists: Donald Trump in the United States; Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil; Narendra Modi in India; Marine Le Pen in France; Matteo Salvini in Italy and Viktor Orban in Hungary.

And so for the first time since the second world war, the great political clash has shifted from between the establishment and assorted progressives, to one between different parts of the establishment: one part appearing as the stalwarts of liberal democracy, the other as the representatives of illiberal democracy.

Of course, this clash between the liberal establishment and the Nationalist International was utterly illusory. In France, the centrist Macron needed the threat of far-right nationalism under Le Pen, without whom he would never be president. And Le Pen needed Macron and the liberal establishment’s austerity policies that generated the discontent that fed her campaigns. Similarly in the United States, where the policies of the Clintons and the Obamas that bailed out Wall Street fuelled the discontent that gave rise to Donald Trump whose rise, in a never ending circle, shored up Clinton’s and Biden’s defences against someone like Bernie Sanders. It was a reinforcement mechanism between the establishment and the so-called populists that has been replicated across the world.

Nevertheless, the fact that the liberal establishment and Nationalist International are, in reality, codependent does not mean that the cultural and personal clash between them is not authentic. The authenticity of their clash, despite the lack of Read more here ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-infocard-contents-90fc79b9-8e43-407f-865c-57a66e147824″ data-initialized-as=”a”>any real policy difference between them, made it next to impossible for progressives to be heard over the cacophony caused by the clashing variants of authoritarianism.

This is exactly why we need a Progressive International – an international movement of progressives to counter the fake opposition between two variations of globalised authoritarianism (the liberal establishment and the Nationalist International) which trap us in a business-as-usual agenda that Read Danny Dorling's analysis of how austerity affects life expectancy in the UK ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-sidenote-contents-9edd0d9a-7c30-4b13-b7c9-69c39d4df837″ data-initialized-as=”a”>destroys life prospects and wastes opportunities Read Jason Hickel's piece on how we need less growth to fight the climate crisis ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-sidenote-contents-3b21a4a7-3e7c-420b-967d-a66330c4fce4″ data-initialized-as=”a”>to end climate change.

The question then is: what would a Progressive International do? To what purpose? And by which means?

If our Progressive International simply creates space for open discussion in city squares (as Occupy Wall Street did a decade ago) or just seeks to emulate efforts such as Read more here ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-infocard-contents-b6a7f7f8-0875-4608-b21c-94111732a116″ data-initialized-as=”a”>the World Social Forum, it will again eventually fizzle out. To succeed we will need a common plan of action and an uncommon campaign strategy to energise progressives around the world to implement that plan. Last but not least, we’ll need the shared will to envision a postcapitalist reality.

Allow me to unpack these three prerequisites one at a time.

Prerequisite 1: A common progressive action plan

The fascists and the bankers have a common programme. Whether you speak to a banker in Chile or to one in Switzerland, to a supporter of Trump in the US or a Le Pen voter in France, you will hear the same narrative. Bankers will say that regulation and capital controls are detrimental to progress; that financial engineering increases the efficiency with which capital flows to the economy; that the private sector is always better at delivering services than the public sector, that minimum wages and trades unions impede growth or that climate change can only be dealt with by the private sector.

For their part, the Nationalist International narrative is as follows: electrified border fences are essential for preserving national sovereignty, migrants threaten local jobs and social cohesion; Muslims in particular cannot be integrated and need to be kept out; foreigners conspire with local liberal elites to weaken the nation; women must be encouraged to raise their children at home; LGBTQ+ rights come at the expense of basic morality and, last but not least: “Give us the power to act in an authoritarian manner and we shall make our country great and you proud again”.

Progressives also need shared narratives. Thankfully, we know what must be done: power generation must shift massively from fossil fuels to renewables, wind and solar primarily; land transport must be electrified while air transport and shipping must turn to new zero-carbon fuels (such as hydrogen); meat production needs to diminish substantially, with greater emphasis on organic crops; and strict limits on physical growth (from toxins to Read about cement in this piece by Maikel Kuijpers ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-sidenote-contents-9d22d365-056f-4666-acb5-24e16069965a” data-initialized-as=”a”>cement ) are of the essence.

We also know that all this will cost at least 10% of global income, or nearly $10 trillion, annually – a sum that can be easily mobilised as long as we are ready to create institutions that will coordinate the various works and redistribute the benefits from the global north and the global south. To accomplish this, we need to invoke the spirit of Franklin D Roosevelt’s original New Deal – a policy that succeeded because it inspired people who had given up hope that there are ways of pressing idle resources into public service.

Our International Green New Deal will have to utilise transnational bond instruments and revenue-neutral carbon taxes – so that the money raised from taxing diesel can be returned to the poorest of citizens relying on diesel cars, in order to strengthen them generally and also allow them to buy an electric car. To plough these resources into green investments, a new Organisation for Emergency Environmental Cooperation, is necessary to pool the brainpower of the international scientific community into something like a Green Manhattan Project – one that aims, instead of mass murder, at ending extinction.

Even more ambitiously, our common plan must include an International Monetary Clearing Union, of the type John Maynard Keynes suggested during the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, featuring well-designed restrictions on capital movements. By rebalancing wages, trade and finance at a planetary scale, both involuntary migration and involuntary unemployment will recede, thus ending the moral panic over the human right to move freely about the planet.

Prerequisite 2: An uncommon campaign

Without this, our common plan, the International Green New Deal, will stay on the drawing table, so here is a campaign idea: let’s identify multinational companies that abuse workers locally and target them globally, utilising the great disparity between the cost to participants of, for example, boycotting Amazon for a day and the costs of such boycotts to targeted firms. Global consumer boycotts are not new but now, using the power of platform megafirms, like Amazon, against them, they can be far more effective. Especially in a second phase, they are combined with local strike action involving the relevant trades unions. Such global action in support of local workers or communities has immense scope. With some clever communication and planning, they can become a popular way people around the world share a feeling that they are helping make the world a freer, fairer place.

Of course, to make this happen, our Progressive International requires a nimble international organisation. The problem with organisations that are capable of global coordination is that they, surreptitiously, reproduce within them bureaucracies, exclusion and power games. How can we prevent neoliberalism and authoritarian nationalism from wrecking the world without creating our very own variety of authoritarianism? Granted, it is harder to find the right answer to this question as progressives who reject hierarchies, bureaucracies and the encroachments of paternalism, but we have a duty to find it nevertheless.

Prerequisite 3: A shared vision of postcapitalism

Consider what happened on 12 August 2020, the day the news broke that the British economy had suffered The Guardian ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-infocard-contents-864325bd-00b0-4c35-9a23-f7d4f02d3a8f” data-initialized-as=”a”>its greatest slump ever. The London Stock Exchange jumped by more than 2%! Nothing comparable had ever occurred. Similar developments unfolded on Wall Street in the United States.

In essence, when Covid-19 met the gargantuan bubble with which governments and central banks have been zombifying corporations and financial institutions since 2008, financial markets finally decoupled from the underlying capitalist economy.

The result of these remarkable developments is that capitalism has already begun to evolve into a type of technologically advanced feudalism. Neoliberalism is now what Marxism-Leninism used to be during the Soviet 1980s: an ideology utterly at odds even with the regime invoking it. Following the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1991, and of financialised capitalism in 2008, we are well into a new phase in which capitalism is dying and socialism is refusing to be born.

If I am right in this, even progressives who still entertain hopes of reforming or civilising, capitalism, must consider the possibility that we must look beyond capitalism – indeed, that we must plan for a postcapitalist civilisation. The problem is that, as my great friend Slavoj Zizek has pointed out, most people find it easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

To counter this failure of our collective imagination, in a recent book entitled Read about this in my recently published book, Another Now: Dispatches from an alternative present ” aria-expanded=”false” aria-controls=”contentitem-sidenote-contents-b9f0dc98-0531-4ab2-ba6c-db8fbf89f76f” data-initialized-as=”a”>Another Now: Dispatches from an alternative present, I try to imagine that my generation had not missed every pivotal moment history presented us with. What if we had seized the 2008 moment to stage a peaceful high-tech revolution that led to a postcapitalist economic democracy? What would it be like?

To be desirable, it would feature markets for goods and services since the alternative – a Soviet-type rationing system that vests arbitrary power in the ugliest of bureaucrats – is too dreary for words. But to be crisis-proof, there is one market that we cannot afford to preserve: the labour market. Why? Because, once labour time has a rental price, the market mechanism inexorably pushes it down while commodifying every aspect of work (and, in the age of Facebook, of our leisure even). The greater the system’s success in doing this, the less the exchange value of each unit of output it generates, the lower the average profit rate and, ultimately, the nearer the next systemic crisis.

Can an advanced economy function without labour markets? Of course it can. Consider the principle of one-employee-one-share-one-vote. Amending corporate law so as to turn every employee into an equal (though not equally remunerated) partner, via granting them a non-tradeable one-person-one-share-one-vote, is as unimaginably radical today as universal suffrage used to be in the 19th century. If, in addition to this pivotal transformation of company ownership, Central Banks were to provide every adult with a free bank account, a postcapitalist market economy would be delivered.

With share markets gone, debt leverage linked to mergers and acquisitions would also become a thing of the past. Goldman Sachs and the financial markets oppressing humanity will suddenly become extinct – without even the need to ban them. Freed from corporate power, unshackled from the indignity imposed upon the needy by the welfare state, and liberated from the tyranny of the profits v wages tug-of-war, persons and communities can begin to imagine new ways of deploying their talents and creativity.

We are at a fork in the road. Postcapitalism is underway, albeit on a path to dystopia. Only a Progressive International can help humanity alter this path.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 2nd, 2020

October 2nd, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: