When millions took to the streets last year to protest for Black lives, corporations saw trouble. The abolitionist call within the uprising – defund the police and invest in a better world – challenges state violence and its profiteers. So, companies like Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft, which enable state surveillance and violence, boosted their public relations. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, for example, declared “solidarity” with Black Lives Matter, and the company donated $250,000 to social justice groups (including the Minnesota Bail Fund).

Thanks to such image-building campaigns, Microsoft doesn’t get scrutinized as much as its peers. The company sponsors think tanks that bolster its progressive credentials and mask the industry’s violent and imperialist agenda. Microsoft also benefits from the aura of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and the Gates Foundation. The New York Times still turns to Gates for advice on how to fix the world’s problems, and runs chummy interviews with Microsoft President Brad Smith to get his insights on the problem of “money in politics.”

But systematically omitted from such coverage are Microsoft’s services to armies, police forces, and prisons around the world – including Microsoft’s investments in Israeli settler-colonialism.

Colonial projects have long served as “laboratories” for states and corporations, and Israel is a prime example. Israel became the model national security state: a regime that controls its populations and puts down uprisings, while producing a fountain of exportable technologies and ideological frameworks. Corporations profit by working with Israel and the US to develop oppressive technologies, and by pushing these technologies into civilian life.

Microsoft provides a bold and sometimes overlooked example of corporations feeding on Israel’s violence. Microsoft cultivates and helps export Israel’s dangerous tools, while presenting Israel as “start-up nation” (a hub of entrepreneurs that supposedly improve the world). Microsoft also gives a window into how corporations sanitize the deadly US-Israeli alliance with the help of non-profits and academic partnerships.

“A marriage made in heaven”

Microsoft opened its first research center outside the US in Israel, in 1991, and today has three branches as part of Microsoft Israel.

Israel has embraced Microsoft’s products, and the company committed to Israel’s industries – enough so that former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer says “Microsoft is as much an Israeli company as an American company.” Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates said that Israel’s developments in “security” were “improving the world,” and current Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella praised Israel’s transformative “human capital.” But Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu went further: Israel and Microsoft were “a marriage made in heaven, but recognized here on earth.”

Indeed, Microsoft has stood by the Israeli government during some of its worst crimes. During the Second Intifada, Israel mounted a murderous assault on the West Bank. In Jenin, Israeli snipers gunned down scores of Palestinians. The Israeli army bulldozed a major part of the city, destroying hundreds of homes and leaving thousands unhoused. Some of the destruction and pain is captured in Mohammad Bakri’s 2002 film Jenin, Jenin (now officially banned in Israel). “They shot at anything that moved, even a cat,” says one man interviewed in the film. Another says, “Everything we built in the last forty-five years was destroyed in five minutes.” The US military had officers on the ground, too, taking notes for the occupation of Iraq.

Following the devastation in Jenin, Microsoft Israel put up billboards along a Tel-Aviv highway with the words “the heart says thanks” to “the forces of security and rescue” – featuring Microsoft’s logo and the Israeli flag. The activist group Gush-Shalom soon called to boycott Microsoft. This was bad publicity, and at the time, the pro-Israel billboards also threatened Microsoft’s business with clients such as Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. So Microsoft pivoted: company headquarters distanced itself from the billboards, which were later removed.

Microsoft’s real investments in Israeli state violence, however, only grew. During the year of the Jenin massacre, Microsoft got a three-year 100-million-shekel contract with the Israeli government (roughly $35 million in current US dollars) – the largest contract of its kind for Israel at the time. As part of the contract, Microsoft agreed to provide unlimited products to the Israeli army and defense ministry, and broadly exchange “knowledge” with the army. According to Israeli newspapers, Israel paid Microsoft from its US “aid” money – a standard way for US corporations to profit by working with Israel.

Microsoft has continued to benefit from Israel’s violence ever since.

Investments in the Israeli military-industrial complex

The Israeli army’s surveillance and counterinsurgency units (such as Unit 8200) produce startups based on military work. They also train a work force that companies like Microsoft want. Over the years, Microsoft has acquired numerous startups emerging from the IDF, sometimes hiring their personnel, and invested in Israeli companies.

Microsoft’s recent investments include AnyVision, an Israeli company that provides the state with cameras and facial recognition software for surveilling Palestinians in the West Bank. AnyVision is suspected to be the manufacturer of a spy camera, planted by Israel in a cemetery in the village of Kober, that Palestinians found and dismantled in October 2019. Following bad press and pressure from activists – including a campaign by Jewish Voice for Peace and a call to boycott AnyVision by the BDS National Committee – Microsoft announced it will divest from the Israeli startup.

But Microsoft didn’t end its relationship with AnyVision. In an interview, AnyVision CMO Adam Devine said he understood Microsoft’s decision to divest since the company “must be sensitive to any potential risk to their brand” – but that AnyVision continues to have “a viable commercial relationship with Microsoft” and use Microsoft’s services. “It’s all good,” Devine added. “They did the right thing and it was fine for us.” Indeed, Microsoft still offers AnyVision’s facial recognition product on its platform.

Besides, Microsoft’s investments in Israel’s military-industrial complex go far beyond one company.

In recent years, Microsoft has acquired Israeli “cybersecurity” companies such as Aorato (in 2014 for $200 million), Adallom (in 2015 for $320 million), Hexadite (in 2017 for $100 million), and CyberX (in 2020 for $165 million) – all based on IDF technologies. Adallom’s co-founder explained that “in the IDF we worked on technologies that were used to combat terrorism using machine intelligence,” and he was interested in how “technologies used to fight terrorism in Israel could be repurposed to help companies mitigate attacks on their data.”

These startups make monitoring technologies that appeal to the US surveillance state and its corporate partners. For example, Aorato’s patents (now owned by Microsoft) include a system for inferring the location of networked devices even in the absence of direct GPS signals. Aorato’s CEO speculated that their products could have prevented Edward Snowden’s leaks by monitoring computer activities. No wonder Microsoft is interested: Snowden’s leaks exposed how Microsoft and its peers collaborated with the NSA, and the Pentagon is Microsoft’s client.

Beyond financial investment, Microsoft also brings its “entrepreneurial” spirit to the IDF. Microsoft sent “mentors” to a 24-hour IDF “hackathon” in which cadets and software engineers developed “creative solutions” for military operations. One hackathon prize-winning app was for “settlement defense” (in Hebrew, “haganat yishuvim”) that “helps solve the lack of commanders control over events inside the settlements and direct communications with the soldier in the field.” Another prize-winning app helps soldiers “calibrate their personal weapons.” With this new solution, “each team commander or firing range manager will have a smartphone application” that calibrates the weapon “according to a known algorithm.” Apparently, all these apps could have “civilian uses,” including for “law enforcement” and “human resources” management.

Gadgets for destruction and state propaganda

Israel’s death industries are necessary for it to be treated as a technological powerhouse. Israel constantly advertises its “high-tech” army, and Microsoft’s gadgets play into these propaganda campaigns. And while details about where and how these gadgets are used are kept secret, they are meant to kill.

For one, Israel uses Microsoft Xbox to control tanks. (The Washington Post presented this as a relatively benign project that raises some “ethical” questions.) According to Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI), Xbox leads to “better performances” – since obliterating neighborhoods is apparently like playing a video game. The Xbox-controlled tank is developed by IAI and Elbit, both makers of drones used to terrorize Palestinians and others across the world. Elbit also helped build the surveillance infrastructure along the Arizona-Mexico border, which encroaches on the land of the Tohono O’odham Nation – showing how the international weapons industry and settler-colonialism work together, both in Palestine and Turtle Island.

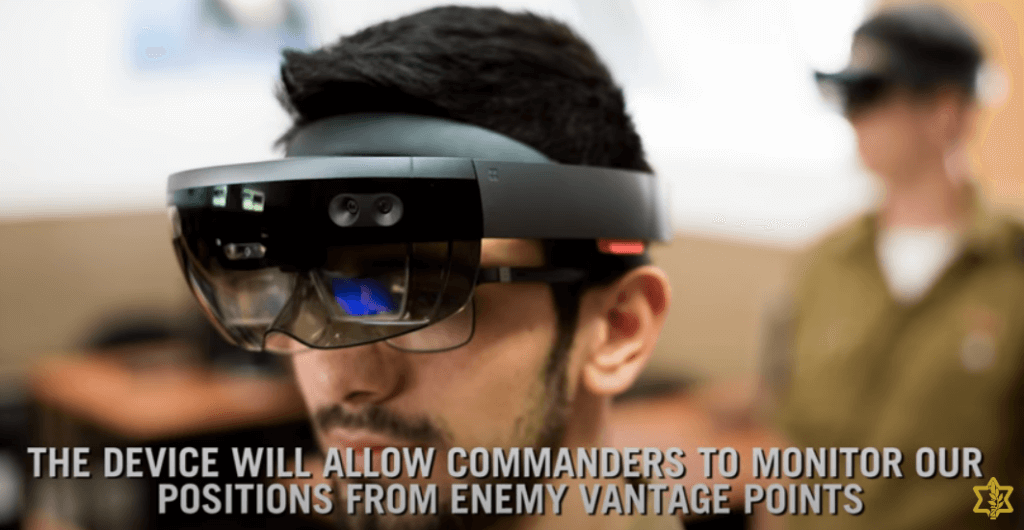

The Israeli army uses Microsoft’s gadgets in official propaganda campaigns. In one video, the IDF claims that Microsoft HoloLens, a “mixed reality” gadget, allows the army to “identify its enemies” and “control robots and drones with gestures.” The IDF adds that they intend “to use HoloLens in the field very soon” – but how and where isn’t said, obviously. As historian Greg Grandin argues, the secrecy of such state operations can become spectacle: we are denied so much specific information that when details are exposed, it’s supposed to feel like a revelation. Yet, as Grandin notes, we already know nearly everything that matters about what the state does.

We know that the Israeli state kills, maims, imprisons, kidnaps, and dispossesses. According to B’Tselem, between 2018 and 2020, Israel has killed over 440 Palestinians, in addition to wounding and maiming thousands in the Great March of Return in Gaza. The state’s recent crimes include the murders of twenty-six year old Ahmad Erekat and fifteen-year old Mohammed Hamayel, the maiming and wounding of teenagers Bashar Hamad and Yusef Taha, and the detention and sexual abuse of children. In September 2020, Israel held over 4,200 Palestinians in prison or detention. Then there is the dispossession: in 2020 alone, Israel demolished 172 Palestinian homes in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), leaving over 900 people unhoused. Israel has continued to evict families and raze villages this year – all while intensifying medical apartheid with respect to Covid protections and vaccine access.

In other words, the latest Microsoft gadget probably isn’t crucial when Israel has soldiers, checkpoints, prisons, tanks, fighter jets, drones, and medical apartheid. But even if the gadget was never used on the ground, both Israel and Microsoft benefit from the idea that it could be. Microsoft profits from the message that its products have “real-world” application, especially by the client that other states try to emulate. Israel benefits from having its military and technological might reaffirmed, and from the backing of a major US corporation. Partnerships with major US entities help to normalize the Israeli state, which is why Israel madly tries to destroy BDS initiatives.

Providing the computerized bureaucracy behind state violence

As activists have long recognized, the daily violence depends on unexciting uses of computing, such as records management – far more so than on attention-grabbing capabilities like facial recognition. Bureaucracy and oppression go hand in hand. And many of Microsoft’s services are more like bureaucracy than high-tech warfare.

Microsoft provides much of the data management behind state violence. According to US government spending reports, over the years Microsoft has received $3.4 billion in federal funds, with roughly 72.6% ($2.4 billion) from the Department of Defense and 14.3% ($488 million) from the Department of Homeland Security – which includes data management contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Recently, the company was awarded a $10 billion contract to build the Pentagon’s data infrastructure (recently contested in court by Microsoft’s competitor, Amazon).

As Michael Kwet reports, Microsoft also services police departments and prisons around the world. It develops software for managing information about incarcerated people, including products geared for “youth offenders.” Microsoft’s carceral products are used by police forces in New York, Washington D.C., Seattle, and Atlanta, as well as in Brazil and Singapore. The company also partnered with a Moroccan firm that gives prisons software for the “management and monitoring of the prisoners, from their incarceration to their release.”

Microsoft also provides essential computing services to Israeli police which is notoriously violent against Palestinians, migrants, as well as Black and Arab Jews. Israeli police claim that “cloud computing provided by Microsoft is necessary for ensuring our operational systems, some of which are classified, run continuously” (Amazon had competed for the same contract). Israeli police also use body cameras made by Taser/Axon, a Microsoft partner. (Microsoft is also opening a “cloud” computing facility in Israel – which contrary to the term, is actually underground – to better serve its Israeli clients.)

These services align with Microsoft’s life-threatening vision of “Connected Policing.” In a brochure describing this framework, the company boasts that its software “helps Israeli police intelligence officers complete data searches in seconds,” compiling information that “once took days to assemble from disparate systems.”

The Israeli army and air force also benefit from Microsoft’s computing infrastructure. The company helped the Israeli army’s Bahad 1, an officer training base, create an app where soldiers can access the IDF’s procedures, triumphalist history, and code of “ethics.” Microsoft also lent a hand in managing the IDF’s civilian human resources database, which tracks the army’s reserve personnel.

Complicity in progressive disguise

Despite participating in state violence, Microsoft is sometimes treated as an enlightened corporation.

Microsoft’s international research centers contribute to this image. Microsoft Israel, for instance, is presented in the language of liberal multiculturalism. “By tapping into our differences and embracing them, our ideas are better, our products are better, and our employees thrive.” The company pinkwashes itself and Israel with declarations like: “we’re proud to champion the LGBTQ community in Israel and collaborate throughout the year on several projects.”

Microsoft also owes its progressive image to the non-profit industrial complex: the nexus of foundations, non-profit organizations, and academia that corporations and billionaires use in their efforts to shape the world.

The company benefits from the association with the Gates Foundation, an enterprise built on Microsoft’s monopoly profits and theft of public monies by tax evasion. The Foundation makes the company and its founder look good, while advancing an imperialist, neoliberal agenda in agriculture and food systems, public health, and climate policy.

Microsoft also sponsored think tanks that do its bidding more directly. These centers hook easily into the neoliberal university, which is always seeking corporate connections and funding. Their work boosts Microsoft’s progressive credentials, but they are silent on the company’s broad crimes and entanglements. And when Microsoft’s smaller crimes do come up, they are contained in the framework of corporate “ethics” and “bias” – masking the industry’s foundational commitment to colonialism and state violence.

Microsoft helped create two influential think tanks, AI Now and Data & Society. AI Now, housed at New York University, was established with a financial “gift” from Microsoft (along with Google funding) and founded by Microsoft and Google employees. It was launched in 2016 with participation and sponsorship from the White House. Data & Society, launched in 2014, was also established with Microsoft’s financial generosity. It is led by a Microsoft employee, and has links to NYU as well. The stated mission of these centers is to study the “social implications” of technology. Occupying the progressive wing of the non-profit industrial complex, such centers gain their power, as Tiffany Lethabo King and Ewuare Osayande observe, from the proximity to “white capital.” They may pepper reports with social justice language but are only accountable to the elite circle that created them. And they never stray far from their patrons’ agenda.

Last summer, for example, AI Now’s co-founder and Microsoft employee Kate Crawford praised Microsoft for announcing it will stop providing facial recognition software to the police – although it was an empty gesture on the company’s part (Microsoft still enables police access to facial recognition through various products). Writing for the prestigious Nature magazine, Crawford also repeated the company’s reformist line that facial recognition should be put on hold because of its “bias” until it can be “regulated” – and only named Microsoft’s competitors, such as Amazon, as complicit with the police. This elevates Microsoft and negates abolitionist alternatives, like the popular demand to ban facial recognition altogether.

Moreover, the fixation of these think tanks on facial recognition already serves the industry’s interests. The focus distracts from Microsoft’s broad and less flashy computing services, which are more essential to state violence. These services are also harder to contain using the framework of corporate “ethics” and “bias.”

Through a discourse on “ethics” and “bias,” these think tanks protect the interests of US industry and empire. The AnyVision scandal makes that clear. Once reported in corporate media, AnyVision’s West Bank surveillance program was harder to ignore, and AI Now commented on the case in its 2019 annual report. AI Now stated that AnyVision is problematic given the “human-rights abuses” taking place in the West Bank. The report adds that AnyVision’s work “contradicts Microsoft’s declared principles of ‘lawful surveillance’ and ‘non-discrimination’” as well as Microsoft’s “promise not to ‘deploy facial recognition technology in scenarios that we believe will put freedoms at risk.’”

AI Now therefore found it “perplexing” that the Israeli startup claimed to have “been vetted against Microsoft’s ethical commitments.” For the think tank, the story of AnyVision ends like this: “Microsoft acknowledged that there could be a problem, and hired former Attorney General Eric Holder to investigate the alignment between AnyVision’s actions and Microsoft’s ethical principles.” Unsurprisingly, the investigation by Holder – an apologist for policing and drone killings – later concluded there was insufficient evidence to support the charge that AnyVision engages in “mass surveillance” or that Microsoft violated its own ethical code.

But there is nothing “perplexing” about this case. Microsoft is implementing US empire’s commitment to Israeli settler-colonialism. By design, the think tanks cannot name these structures. Ironically, though, in another part of the same report that isn’t about Israel, AI Now emphasizes that using “decolonization” in the abstract “can allow narrow economic interests to co-opt the rhetoric of decolonial struggles.” When it is about Microsoft and Israel, the think tank perpetuates the farce of “lawful surveillance” and corporations abiding by ethical codes. Yet Microsoft’s support for AnyVision is entirely consistent with Microsoft’s history and operation, and there is no real difference between Microsoft’s violent projects and AnyVision’s. AnyVision is only one window into Microsoft’s deep commitments to war, incarceration, and colonialism.

Given these commitments, Microsoft’s appeals to “social justice” should be viewed as part of a counterinsurgency effort: an attempt to quell rebellion and divert from abolition. And Microsoft’s $250,000 donation to social justice groups is a pittance compared to the untold billions the company makes from enabling state violence. One hand kills while the other tosses crumbs.

Divesting from state violence, investing in communities

Activists haven’t been fooled by corporate public relations. Grassroots groups in both Palestine and the US – such as Stop the Wall and Stop LAPD Spying Coalition – have exposed how Microsoft and its peers circulate oppressive tools internationally for profit and control.

Stop the Wall in Palestine sees corporations like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft as colonizing forces that benefit from “Israel’s decades old regime of apartheid, colonialism and occupation over the Palestinian people” and help to maintain the regime. As Stop the Wall writes, Israel’s “surveillance of the Palestinian people offers technology of data collection and processing,” which is then applied in areas “from smart cities to advertising.”

For Stop the Wall, resistance to this system is also a labor struggle, since these companies’ political power is built on exploited and unfree labor, and because the surveillance methods used in colonial projects are linked to those used at home. It is why Stop the Wall sees the “Palestinian struggle within the framework of internationalism and intersectional solidarity.” Stop the Wall seeks to dismantle the walls – not just the physical ones, but the wider policing apparatus built jointly by Israel, the US, and private corporations – through boycotts and divestment. The group calls for “an end to military relations with Israel and the defunding of its military and homeland security complex.”

In Los Angeles, Stop LAPD Spying Coalition also recognizes the commonalities between oppressive regimes across the globe and their shared set of profiteers. The Coalition is pushing to defund the Los Angeles Police Department for its racist and murderous operations, including its efforts to confine communities using invisible walls (LAPD stores surveillance data on Microsoft’s platforms). But the Coalition emphasizes that the same tools are used elsewhere, and commits to the Palestinian struggle in its statement of principles. Stop LAPD Spying Coalition calls to defund the broad surveillance complex and invest instead in housing, public health, food security, public spaces, and non-carceral ways of coping with harms and emergencies.

The abolitionist thread in these initiatives holds promise. Strategies such as divest/invest could begin to starve the industries of violence by redirecting their resources towards restorative ends. May these efforts multiply, everywhere, to help realize the demands of millions who took the streets.

Yarden Katz

Yarden Katz is a fellow in the Department of Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School and the author of Artificial Whiteness: Politics and Ideology in Artificial Intelligence (2020).

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 15th, 2021

March 15th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: