Throughout history, every major culture has stories of reptilian monsters who threatened their livelihood. From the Egypt to India, and even the Sioux Nation, tales of these flying dinosaurs or winged lizards have filled the cultural imagination of societies throughout the ages. Today we explore the possible depiction of the pterodactyl, a genus of pterosaur, in modern New Guinea .

Depiction of a dragon from 1588. ( Public domain )

Historic Tales of Dragons and Reptilian Monsters

The Egyptians were said to be invaded each year by flying serpents from Arabia that threatened their frankincense trade, while Alexander the Great encountered a great hissing dragon when he invaded India. In 1035, a terrible dragon was killed in the swamps of Hungary, the memory of this event living on through the royalty of the Báthory family and the Báthory seal.

In Kradów, Poland, a dragon was said to terrify the inhabitants, requiring weekly an offering of cattle to appease its appetite lest it devour human flesh. The dragon’s demise, according to Polish folklore, traces to a poor cobbler’s apprentice. Cleverly concealing smoldering sulfur in the skin of a calf, this apprentice caused the fiery death of the dragon. Today, large bones said to belong to this dragon hang from the ceiling of the Wawel Cathedral.

The King of the Gauls had been presented with the remains of a winged dragon called Brodeus while in Styria, in 1543. The historian Gessner described it as having “feet like lizards, and wings after the fashion of a bat, with an incurable bite.” In Conrad Gessner’s five volumes of natural history, Historiae Animalium, published in the 1500s, he described dragons as “very rare but still living creatures.”

The Sioux Nation has a rich tradition of passing down stories from generation to generation. Some of these describe large flying reptiles known as “ thunderbirds.” Stories depict these flying monsters as having been so large that their wing beats created the thunder while the wings themselves tore the clouds, bringing rain (Bouck and Richardson III, 2007). The Dakota Sioux called these thunderbirds wakinyan, and pointed out collapsed river bluffs as places where the wakinyan swooped down on Unktehi, a monstrous water reptile (Pond, 1986).

Regardless of the culture describing these unique, flying monsters, authors of these accounts generally agreed that dragons were evil and destructive. This was, perhaps, the inspiration for the writers of the Bible using them as metaphors for and symbolic of the devil. Jews and Gentiles in Biblical times would have been intimately familiar with stories and myths of dragons, and their incorporation into these writings add further evidence of their widespread knowledge.

Coat of arms of the Hungarian Báthory family which depicts a dragon. (GiMa38 / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Accounts of Reptilian Monsters in Modern-Day New Guinea

Today, there are still accounts of reptilian monsters said to haunt and harass villages throughout the remaining corners of largely unexplored forests, mountains and oceans of the world. One such place is the Bismarck Archipelago where Papuans of New Guinea give accounts of the Ropen, Duwa, or Orang–bati. Though minor differences occur in the individual accounts of these animals, overall appearance and habits remain consistent. All agree that this rare and dangerous monster dwells in the mountains along some cleft, sometimes resting on the trunks of trees, until night falls when they make their appearance.

Though occasional daylight observations occur, the Papuans agree that the animal is largely nocturnal. The most conspicuous characteristic of the animal is its bioluminescent abilities. When observed, the creature is said to fly from the mountains to the reef where it is believed to feed on fish, squid and the giant clam. On occasion, the monster has made attacks on human lives, even digging up the graves of the recently interred. This is the reason for the people in these regions now covering their graves with rock or concrete.

When observed during the day, specific anatomical characteristics are described that enable the investigative enquirer to make conjecture on the family to which these animals belong. Like dragon stories of the past, the Ropen or Duah, has two membranous wings like those of bats. Its body is covered in short hair and yet they are described as reptilian, with a mouth full of teeth and a horny crest at the back of the head. A long, rigid tail trails behind that is tipped with a diamond-shaped flange.

Though the people describing these animals are not scientists, they can describe details of the animal that match paleontological evidence. For instance, the natives state the tail of the Ropen is stiff, being incapable of bending but for where it attaches to the body. This agrees favorably with fossils that show the vertebrae of Rhamphorhynchoid tails being interlocked (Whitcomb, 2009), making them rigid but for the base, thus serving as a rudder that could be swung back and forth in flight (Cranfield, 2001).

![]()

Rhamphorhynchoid tail vertebrae

Pterodactyl Bioluminescence Described Through the Ages

Ropens are said to be brightly bioluminescent, filling villages they pass with their light that can be red, blue, green, or yellow. This claim is closely mirrored by ancient accounts like the one given by the prolific 17 th century writer Athanasius Kircher:

“On a warm night in 1619, while contemplating the serenity of the heavens, I saw a shining dragon of great size in front of Mt. Pilatus, coming from the opposite side of the lake, a cave that is named Flue moving rapidly in an agitated way, seen flying across; it was of a large size, with a long tail, a long neck, a reptile’s head, and ferocious gaping jaws. As it flew it was like iron struck in a forge when pressed together that scatters sparks. At first I thought it was a meteor from what I saw. But after I diligently observed it alone, I understood it was indeed a dragon from the motion of the limbs of the entire body. ” (Kircher, 1664)

The sparkler effect as observed by Athanasius Kircher is very similar to modern accounts (Whitcomb 2007; Whitcomb 2011) that occasionally describe a shimmery edge to the bioluminescent glow of the creature. This could be related to another characteristic of the creature rarely described, yet backed by further historical evidence. In his book Aelian on Animals 16. 41, Claudius Aelian wrote that in India there were “snakes with wings, and that their visitations occurred not during the daytime but by night, and that they emit urine which at once produces a festering wound on any body on which it may happen to drop (Aelian, 1958).”

It is in fact these winged snakes ( ophies) which Aelian accounts for the cause of the Egyptians holding the ibis sacred. In Aelian on Animals 2. 38, he wrote “the Black ibis does not permit the Winged Serpents ( Ophies Pterotoi ) from Arabia to cross into Aigyptos, but fights to protect the land it loves (Aelian, 1958).” Once more, these ancient accounts coincide with modern evidence; people on the island of Umboi between Papua New Guinea and New Britain, claim the Ropen secretes a substance that occasionally falls on the people, causing burns on the skin (Whitcomb, 2007).

Hidden in Plain Sight: Pterodactyl on the Siassi Tami Feast Bowls

If these strange stories are to be believed shouldn’t we expect evidence in some form, particularly when the colorful dances, paint and wood carvings of the Papuan people represent known species prevalent in the Bismarck Archipelago? Perhaps the evidence has been hidden in plain sight, our own bias preventing our eyes from seeing what stands before them. An investigation into the artifacts of the Bismarck heritage reveals many artistic forms of human skill, and hidden within these artifacts are revelations waiting for a knowing eye to notice and bring to light. One such artifact that has caught the attention of curious minds are the Siassi Tami feast bowls.

The Tami bowls of New Guinea are made from a single large piece of hardwood called kwila. Often oval in shape, these are skillfully carved with reliefs of animals and human figures, each design being unique to family groups, serving as trademarks of kinship. Hollowed out by burning, and laboriously carved with stylized images, these are infilled with lime, and skillfully patinated by rubbing them vigorously with volcanic ash.

Production of these unique bowls are heavily localized on the islands of Tami from which they are traded out to others in the Siassi Islands, a 200-mile region that today reaches as far as the Caroline and Solomon Islands. These bowls have two uses; one being ceremonial, used for the preparation of food during feasts and rituals, and they can serve as dowry which young men pay to the parents of their bride. A native heirloom, these bowls are passed down from generation to generation.

A careful study of these Tami bowls can offer a glimpse into the lives, ideology and environment of the people who trade and own them. One particular bowl of interest can be found on the Oceanic Arts Australia website. While the authors of the site offer no interpretation regarding the details of this Tami bowl, apart from its representation of balum, a benevolent spirit, there are two strange forms found on either side which at first appear simply artistic, but on closer inspection would seem anything but. On this bowl are found two winged forms supported by two powerful legs, and possessing anvil-shaped heads. At first one might envision a stylized bird of some kind, or at most an unknown spirit. However, as one carefully dissects the details depicted (Figure 1), another possibility arises.

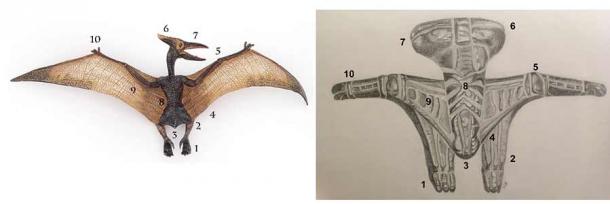

Comparison of stylized pterodactyl from a Tami bowl to an anatomical model. Artistic rendition of Siassi Bowl motif from Oceanic Arts Australia. ( Oceanic Arts Australia )

The Tami bowl figure clearly demonstrates clawed feet (1), and indicates where the knee joint (2) of the legs exist. Note this is relatively close to how scientists believe the knees rested slightly below the wing membrane. The figure also demonstrates a triangular protrusion (3) where the tail-bone on a pterodactyl would have existed, as well as representing the wing membrane smoothly transitioning to its attachment (4) with the tail-bone.

A decorative flourish (5) along the wing exists roughly where the first joint after the elbow would have connected to the leading edge of the wing. The head of the Siassi Tami Bowl creature also depicts what could be a horny crest (6) that is slightly shorter than the mouth (7) as demonstrated in some pterodactyl fossils. Stylized ribs (8) demonstrate a thin-body, whereas a fleshy representation of the wing membrane (9) exists between the bony structures of the wing. Finally, another flourish (10) could represent the fingers of the wings.

Could It Really Depict a Pterodactyl?

As seen in the figure above, the mysterious form compares favorably to the anatomy of a pterodactyl. The anvil-shaped head could represent the crested head of such an ancient animal, whereas the wings demonstrate simple, yet fascinatingly comparable features to those of a pterosaur. One must remember on observing these forms that the Papuan artists who carved these bowls were not scientists. Yet despite this, the features seen here are remarkably accurate for a design intended merely for trade. Stylized flourishes exist at roughly the same points on the wings where the joints would have existed on the wings of pterodactyls, remarkably close when one considers the Ropen has always been observed distantly by the locals.

If any close examination of Ropen biology by a native hunter has occurred in the past, this account has certainly been lost. Nevertheless, it can be argued that the similarities between the form and its possible representative are uncanny. Further, the Tami bowl forms demonstrate smooth, arching of the lower “wings” as they transition to the “legs” of the design, very much like on a pterosaur where the wing membrane smoothly curved until uniting with the tail-bone between the two hind legs.

Further study reveals two more Siassi Tami bowls with similar designs of what could represent a pterosaur, though the details are more stylized and less refined than that on the Oceanic Arts Australia Tami bowl. Seen in the following images are two further potential pterosaur designs.

Detail from feast bowl from Siassi Tami bowl showing what could be a pterosaur. (Amélie Godreuil)

Early 20 th Century wooden feast bowl from Papua New Guinea. (Courtesy of Bowers Museum )

Once again, these Tami bowls reveal creatures whose wings connect to the body at the joint of the tail bone, a feature not displayed in modern birds. Further, the motif in image 3 compares uncannily to an indigenous wood carving (Images 4 and 5) on display in Port Moresby and photographed by David Woetzel during an expedition to Papua New Guinea. This carving depicts a bizarre creature with lizard-like ears, forked tongue, long snake-like neck, a shallow beak, membranous bat-like wings, dermal bumps running the length of its back, webbed feet and long tail.

Left: Image 4 – Side view of Ropen Statue. Right: Image 5 – Front view of Ropen Statue. ( Genesis Park )

Though it cannot be proven that the Ropen statue of Port Moresby is the same creature displayed on the Huon Peninsula Siassi Tami feast bowl, they do share anatomical features including featherless wings and a reptilian head. The main difference is in the tail: the Siassi bowl motif lacks a tail whereas the Port Moresby statue has a long tail. Yet even this can be accounted for by native accounts of the Ropen, with most agreeing the creature has a long tail, while a few accounts claim there was no tail at all.

If these stories are to be believed, they would suggest two species present on the Bismarck Archipelago islands, and these appear supported by native works of art. Could it really be possible that the native artwork found on Tami bowls provide evidence for the existence of modern pterosaurs? While it cannot be proven yet, and there is skepticism in the scientific community about theories of modern-day dinosaurs, it does offer a fascinating possibility.

Top image: Could the artwork on Tami bowls in New Guinea have been inspired by sightings of modern-day pterodactyl? Source: satori / Adobe Stock

Shalee Britton is a Wildlife Biologist, writer and cryptozoologist from Texas, USA. Her novel ‘Captain Alonzo Johnson: Journey into the Unknown’ is available from Lulu Bookstore , or on Amazon.

References

Aelian. 1958. Aelian on Animals, Books 2 and 16. Harvard University Press.

Black, R. August 16 2010. “Don’t Get Strung Along by the “Ropen” Myth” in Smithsonian Magazine . Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/dont-get-strung-along-by-the-ropen-myth-78644354/

Bouck, J., & Richardson III, J. B. 2007. “Enduring Icon: A Wampanoag Thunderbird on an Eighteenth Century English Manuscript from Martha’s Vineyard” in Archaeology of Eastern North America , 11-19.

Cranfield, I. 2001. The Illustrated Directory of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Creatures , Greenwich Edition. London, UK: Book Sales.

Kircher, A. 1664. “Dragons” in Mundus Subterraneus , pp. 179-180.

Pond, S. W. 1986. The Dakota or Sioux in Minnesota as They Were in 1834 . Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Whitcomb, J. D. 2007. Searching for Ropens: Living Pterosaurs in Papua New Guinea . WingSpan Press.

Whitcomb, J. D. 2009. “Reports of Living Pterosaurs in the Southwest Pacific” in Creation Research Society Quarterly (45).

Whitcomb, J. D. 2011. Live Pterosaurs in America . CreateSpace Independent Publisher Platform.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 4th, 2021

February 4th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: