A woman stands next to a large flame, with a staff in one hand and tending to the fire with the other. This is Hestia, the Greek goddess of the hearth, home, and family. Her name literally means “hearth” or “fireplace.” Although Hestia may not be the strongest among her peers, she holds great importance in the social and religious life of the ancient Greeks.

In Greek mythology, there is little mention of the goddess Hestia because while the other deities enjoyed the freedom to do what they wanted, she was always at home tending to the sacred hearth. She is known for being pure and peaceful and spent most of her time tending to her duties. Her attitude of keeping herself to herself meant that she appeared in very few myths, but there are myths in which her personality shines through.

A closeup of Rome’s famous Giustiniani Hestia statue, made from pure white marble because she was pure and uniquely neutral. (Ed Uthman / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Who was Hestia?

Before the coming of the Olympians, there existed the Titans. Among them, the most important Titans were Cronos and his consort, Rhea. When Rhea became pregnant, Cronos discovered a prophecy that declared that one of his children would overthrow him and take control. Fearful of the prophecy, he decided on an extreme course of action. In many sources, the firstborn of Cronus and Rhea is believed to be Hestia.

As Homer writes in his fifth hymn:

“She was the first-born child of the wily Cronus, and the youngest too.”

Although this phrase may seem confusing, it is referring to the fact that the Olympians were in fact, born twice. First from their mother, Rhea, and then again when they were rescued by Zeus, who made Cronus expel his siblings trapped in his stomach. As the eldest, Hestia would have been the first to be swallowed and the last to be thrown up, as she may have been at the very bottom of his stomach.

She, along with her siblings; Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, Zeus, and Hades, fought against the Titans to assume control. Once the siblings, gained a victory against their tyrant father and the other Titans, they established their seat of power at Mount Olympus. Zeus took the title of “king of the gods,” marrying Hera, who became the “queen of the gods.” He granted each god a domain that they had control over. Slowly the Olympian pantheon increased in size, to include numerous new deities like Hephaestus, Athena, Artemis, Apollo, and many others. But Hestia was different.

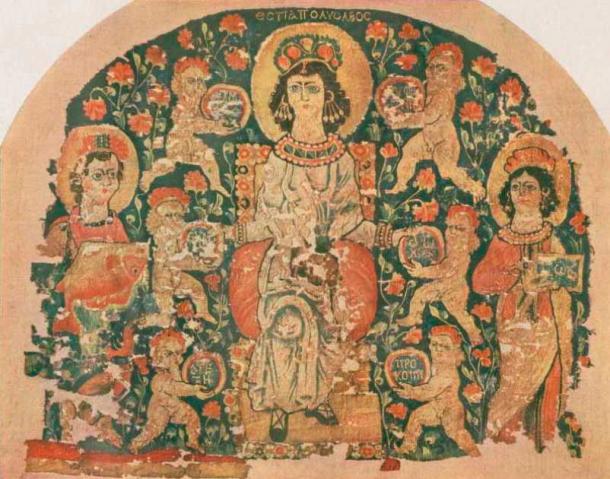

The 6th-century AD Egyptian Hestia tapestry, scanned from the 1945 book Documents of Dying Paganism, in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Washington D.C. ( Public domain )

Did Hestia Marry?

Unlike her younger sisters, Hera, who married Zeus, and Demeter, who had children with Zeus, Hestia decided to remain a virgin. Despite being approached by several suitors, like Poseidon and Apollo, who proposed to her. Hestia was determined to remain a virgin and she let her desire be known as Homer writes in Hymn no.5:

“…by the will of Zeus who holds the aegis, — a queenly maid who both Poseidon and Apollo sought to wed. But she was wholly unwilling, nay, stubbornly refused; and touching the head of Father Zeus who holds the aegis, she, that fair goddess, swore a great oath which has in truth been fulfilled, that she would be a maiden all her days.”

The connection between Hestia and Apollo and Poseidon, seen in the quote above, is also mentioned at the Temple of Delphi, where all three were worshipped together. Also, Hestia and Poseidon often appear together at Olympia. The fact that the three gods were so closely linked meant that Hestia would have been aware of the competition between the two male gods that may have contributed to her decision to remain unmarried.

Again, Hestia’s decision to remain a virgin may have been propelled by her desire to prevent internal strife between the gods. She was aware that no matter whom she chose, the rejected suitor would create chaos, and so she sacrificed her desire for marriage, to maintain peace among the Olympians. Homer mentions how moved Zeus was by his sister’s decision and the respect he granted Hestia.

“So, Zeus, the father gave her a high honor instead of marriage, and she had her place amid the house and has the richest portion. In all the temples of the gods, she has a share of honor, and among all mortal men she is chief of the goddesses.”

The quote “the richest portion,” means that in all sacrifices the best and first part of the sacrifice will be given to Hestia and then to the other gods. Thus, even though Hestia didn’t have a temple, she would be invoked before all other gods, so she was present in all religious temples.

Hestia’s Role in Greek Society

The hearth symbolized the heart and soul of each Greek household; thus, it came to represent the center of the home. Hestia presided over the fire burning in the hearth, therefore, she was believed to be the goddess of domestic life, and by pleasing her, she would provide domestic happiness and blessings.

Hestia was present in the preparation and cooking of the family meal. But the hearth was used in many other activities besides cooking. When a baby was born, they would perform a birth ceremony, in which the baby would be carried around the hearth. New members of the household, like brides or even slaves, sat in front of the hearth and were bathed in nuts and figs, which were Hestia’s blessings. And, when a member of the household died, the fire would be extinguished and then relit, signifying the loss of a loved one.

The family hearth was also the religious center of the household. The residents of the house could send offerings and small sacrifices to Hestia at the hearth. The women carefully tended to the fire, in reverence for Hestia because the Greeks believed that if the fire were to go out, it was bad luck for the family. And it was seen as a sign that the goddess had removed her favor from the family. Though, if the fire did go out the residents could go to the public hearth and use it to relight their home fire.

An important aspect of Hestia is that no temples were erected in her honor. However, a public hearth usually existed in the prytaneum, a public building in ancient Greece. Hestia was represented by the sacrificial fire at which the prytanes, officials in the Greek cities, offered sacrifices to her upon entering office.

The public hearth was considered a sacred asylum in every town, where the prytanes would receive guests and foreign ambassadors. When the Greeks would send out a colony, the emigrants would take a part of the fire with them. The sacred flame would burn in the hearth of their new home, a connection to their mother city. A fire that went out was a bad omen for the Greeks, and if it did go out, it could not be lit again with ordinary fire. Two methods were to be employed to relight the flame: the first was by producing fire by friction, and the second, with a sun glass.

Evidence of the importance of the hearth goes as far back as the Mycenean period, where the hearth was the focal point of the home. Palaces from that era had a central hall (megaron) that had a throne room with a hearth, the presence of it in such a prominent place is evidence that the worship of Hestia extends back to that time.

In the Titanomachy, when the Titans took on the Olympian gods, Hestia was the only Olympian to stay out of the fight altogether. ( matiasdelcarmine / Adobe Stock)

What Hestia’s Role in the Epic Titanomachy Battle?

As an original Olympian, Hestia was aware of the various plots to dethrone Zeus, king of the gods, but they were always from outside the circle. However, when a coup was being planned by Hera, queen of the gods and wife of Zeus, the Olympians were forced to choose sides. Hera needed assistance from Apollo, Poseidon, and Athena, but these gods also desired to possess the throne for themselves.

Hera fed her husband a drug that made him fall into a deep sleep, then the other gods chained up the sleeping god. After Zeus was no longer a threat, a debate as to who would be the next ruler began. The only Olympian who did not participate in the coup was Hestia, who wasn’t interested in power. However, Hestia also decided to keep her distance, as she wasn’t strong enough to oppose her stronger siblings.

Ultimately, Zeus was freed by his allies, the Hecatoncheires, “the hundred-handed ones,” and they helped Zeus restore power and control. Being betrayed by those he had trusted, meant that Zeus would exact punishment. While the other gods, like Hera, Poseidon, and Apollo, were punished, Hestia was spared.

Hestia, Priapus, and the Donkey

At a grand feast held by Rhea, the gods and goddesses got together to celebrate. There was feasting and great enjoyment, and wine flowed freely, which led to the entire party getting intoxicated. At the time, Hestia decided to sleep outside, after tending to her duties. The drunk partygoers were stumbling around trying to sober up, among them was Priapus, a minor fertility god who was looking for nymphs to get frisky with.

Seeing Hestia asleep, he slowly made his way to her, but before he could do anything Silenus came stumbling on the scene with his donkey. The donkey started braying, which woke up the sleeping goddess and alerted the gods. Hestia pushed Priapus away, while the other gods gave him a beating for trying to harm Hestia.

The donkey that had awoken Hestia was honored, on Hestia’s feast day, the Greeks placed garlands on the donkeys, and they were allowed to rest the entire day.

A fresco of Vesta-Hestia from Pompeii, Italy, which shows that Hestia continued to thrive as the hearth and home goddess in Rome. (Mario Enzo Migliori / CC0)

Who is Hestia’s Roman Equivalent?

Vesta, the goddess of the hearth and home, is believed to be Hestia’s Roman counterpart. Both goddesses shared the same importance in state and home, but Vesta’s importance was promoted by her priestesses, the Vestal Virgins. The main role of the Vestal Virgins was to tend to the sacred fire, located in the Roman forum, in the temple of Vesta. The Romans held the belief that if the sacred fire was ever extinguished then Rome would fall.

Apart from Vesta, according to Cicero, Hestia was also associated with the Penates. The Penates were believed to be Roman gods of the home, and they were often associated with other deities of the house like Vesta.

Imagery and Symbolism

Hestia has very few pictorial representations. If portrayed it would be as a modest middle-aged woman, who wore a veil. She would often be painted or sculpted while holding a staff or a flowered branch.

Conclusion

In mythology, Hestia is like no other, she was a goddess devoted to her task of keeping the Olympian hearth burning. She protected the Greek house and kept the fires burning in the house. She may not have been one of the most famous goddesses of Greek mythology, but her importance is second to none. After all, home is where the heart and hearth live, so she held a special place in the heart of the Greek people.

Top image: Hestia, the Greek goddess of the hearth and home, holding the flame of life. Source: matiasdelcarmine / Adobe Stock

By Khadija Tauseef

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 20th, 2022

September 20th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: