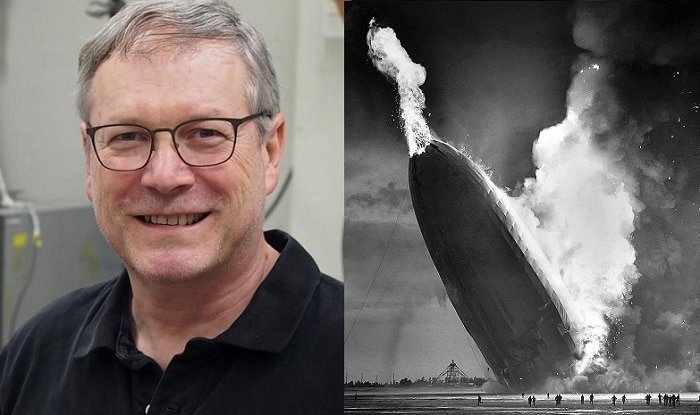

Greek scientist Konstantinos Giapis has finally solved the mystery of the Hindenburg disaster, the destruction of the largest aircraft ever built by mankind, on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey.

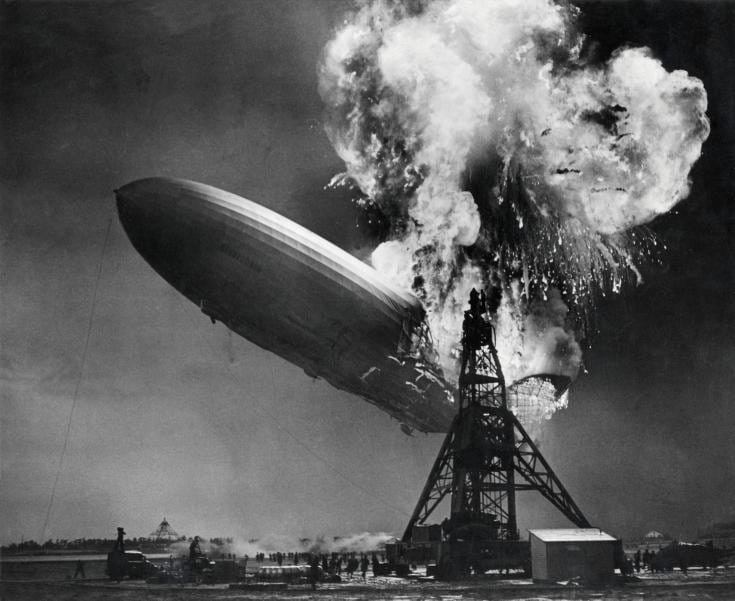

The airship Hindenburg was nearing the end of a three-day voyage across the Atlantic Ocean from Frankfurt, Germany before it went up in flames. It was a spectacle and a news event just to watch the gigantic airship making its way across the skies. Onlookers and news crews gathered to watch the 800-foot-long behemoth touch down.

And then, in one horrifying half minute, it was all over. Flames erupted from the airship’s skin, fed by the flammable hydrogen gas that kept it aloft, and consumed the entire structure, ending 36 lives.

The ship, already famous before its demise, was seared into the world’s memory.

The disaster, despite happening nearly one hundred years ago, has remained one of the iconic tragedies of the 20th century, alongside other accidents that captured the public imagination, like the sinking of the Titanic, the Challenger explosion, and the meltdown of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor.

Greek scientist unravels the cause of the explosion

But what caused the explosion? Caltech’s Giapis, professor of chemical engineering, recreated the ship’s last moments and unraveled its secrets for NOVA, the popular PBS science television show.

Giapis, who obtained his diploma from the National Technical University of Athens in 1984 and finished his Ph.D. studies at the University of Minnesota in 1989, began looking into historical records of the accident, and soon realized that no one had done experiments to try and find out what had actually happened.

What has always been known is that the zeppelin, which was designed by the Zeppelin Company, a German firm known for its large and luxurious airships, contained 7 million cubic feet of flammable hydrogen.

Imagine a cigar-shaped balloon as large as a skyscraper filled with explosive gas. Combine that hydrogen with oxygen from the air, and a source of ignition, and you have “literally a bomb,” Giapis said, according to an interview with Caltech.

The key, but long-unanswered, question: How was the fire sparked? The Greek scientist built a model of a portion of the zeppelin’s outer surface in his laboratory on the Caltech campus to get the answers.

Building a model of the Hindenburg airship

The Greek scientist says that after the ship was grounded, it became more electrically charged. When the mooring ropes were dropped, electrons from Earth’s surface moved up to the frame, giving the ship a positively-charged skin and a negatively-charged frame.

In other words, by grounding the frame with the mooring ropes, the landing crew had inadvertently made more “room” for positive charge to gather on the ship, setting the stage for the disaster.

“When you ground the frame, you form a capacitor — one of the simplest electric devices for storing electricity — and that means you can accumulate more charge from the outside,” Giapis says. “I did some calculations and I found that it would take four minutes to charge a capacitor of this size!”

With the ship now acting as a giant capacitor, it could store enough electrical energy to produce the powerful sparks required for igniting the hydrogen gas — which, based on eyewitness accounts, may have been leaking from the rear of the ship near its tail.

“Hydrogen was leaking at one specific location in this humongous thing. If there is a spark somewhere else on the ship, there is no way you would ignite a leak hundreds of feet away. A charge could move on wet skin over short distances, but doing that from the front of the airship all the way to the back is more difficult,” he says. “So how did the spark find this leak?”

Any place where a part of the frame was in close proximity to the skin would have formed a capacitor, and there were hundreds of these places all over the ship, Giapis says.

“That means the giant capacitor was actually composed of multiple smaller capacitors, each capable of creating its own spark. So I believe there were multiple sparks happening all over the ship, including where the leak was,” he says.

Giapis’ work could help exploration of Mars

The Greek scientist was also the head of a team of US scientists who have developed a small, portable device that can generate oxygen from carbon dioxide.

His brilliant idea could become the foundation of future human missions to Mars, as it could provide breathable oxygen to astronauts who will travel on long space missions to reach the red planet.

After finishing his Ph.D. studies at the University of Minnesota in 1989 Giapis worked as a Lacey Instructor in Caltech between 1992 and 1993; as an Assistant Professor between 1993 and 1998; and an Associate Professor between 1999 and 2010. Since 2010 he has been a Professor at Caltech.

He is currently teaching Chemical Engineering Design Laboratory and Heterogeneous Kinetics and Reaction Engineering at Caltech.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 18th, 2021

May 18th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: