In Gordon Lightfoot’s 1976 song The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald , he figuratively blames the sinking of that ship on the “witch” of November. Folks more familiar with Ojibway mythology might, however, have pointed to Mishipizheu, one of the most important of the underground mythological creatures of the Northeastern and Midwestern North American tribes.

This pictograph of the Great Lynx known as Mishipizheu was created by Ojibway spiritual leaders at Agawa Rock in Lake Superior Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada. ( Chris Hill / Adobe Stock)

Was Mishipizheu a God or a Monster?

The “Great-Lynx” Mishipizheu blurs the line between god and monster and thus sheds light on what it takes to be one or the other. The Ojibway, an indigenous people from southern Canada and the northern Midwestern United States, believed Mishipizheu was a giant lynx-like creature. An apt description would be that the Mishipizheu was a horned panther covered in copper scales with razor-sharp spikes down its back and a long flexible tail.

According to Ojibway mythology, Mishipizheu lived under the vast waterways of their territory in the Canadian Shield, in and near the Great Lakes. It exercised complete control over the waterways and had a mean-streak which had to be placated with copper or tobacco offerings lest it use its tail to create violent whirlpools or harsh waves to drown the people residing in the area.

On the one hand, we might consider him a god as he exercised supernatural power over a vast area of waterways and accepted tokens or sacrifices for his cooperation with human endeavors. On the other hand, he is primarily a malevolent presence, drowning those who forget their offerings to him, creating tumult capriciously with a whip of his tail, and standing in opposition, in many stories, to the heroic Thunderbird. He was godlike in his power, but monster-like in his malevolence.

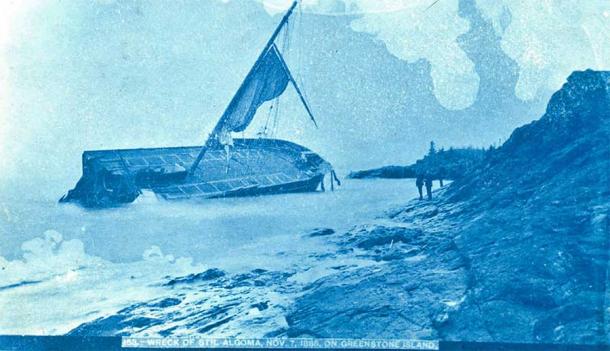

The SS. Algoma went down on Lake Superior in 1885. It was the worst loss of life in the history of Lake Superior. ( Public domain )

The Malevolent Intentions of Mishipizheu the Underwater Panther

It is no wonder that a malevolent spirit was felt to inhabit Lake Superior. Some people believe Mishipizheu has sunk at least 400 ships on the lake in recorded memory alone, in addition to the Edmund Fitzgerald. Some have even said that the island of Michipicoten, in Ontario (Canada) in the northeastern part of Lake Superior, is the primary abode of Mishipizheu, when he is not swirling through underground tunnels and caverns throughout the region.

The belief of indigenous tribes of the region is that Mishipizheu lives and travels through a vast system of tunnels and caverns underlying the vast waterways of Midwestern United States and Canada, often wreaking havoc on those who sail those waters. But, why?

Mishipizheu guards the vast amount of copper which, to this day, lies within the Great Lakes . Native inhabitants of the Great Lakes region, stretching back to about 7,500 BC, discovered copper that was 99% pure in Lake Superior, in veins or just lying around in nugget form. Initially they used the copper for spear points and tools, but as a larger social organization developed the copper was used for personal ornamentation denoting social standing.

There was only one problem. Lake Superior was not a gentle lake to those extracting the copper, in fact it was quite fierce. The fierceness was attributed to a creature which seemed obviously to be guarding the copper. Hence the existence of Mishipizheu. Indeed, if we dig a little deeper, the belief in this creature points to why monsters were created in the first place. In pre-scientific cultures, folks often attributed evil intentions or ill will to events possessing no evil intentions or ill will.

To this day, in some villages, when someone falls ill a shaman might declare that a personal enemy sent an evil spirit to possess the victim. A person does not just fall ill, someone or something must desire that. Thus it is with the sea and other bodies of water. Unpredictable tragedies occurred and we were quick to attribute the tragedies to an invisible malice or ill will. Anything other than natural causes.

We seem to be wired, for whatever reason, to be super-keen to perceive and attribute malice and malevolence to adverse things that happen to us. It was too difficult for us to believe that things affecting us negatively could just happen. Mishipizheu became the figuration of the malice of the sea, part godlike in his scope, mostly monstrous in his intentions. But, interestingly, we attributed a reason for his malice – his irrational desire to possess all the copper in Lake Superior.

Stormy sky over Lake Superior, the home of Mishipizheu. ( boundlessimages / Adobe Stock)

Mishipizheu Ancillary Stories

The odds are that the origin of the Mishipizheu myth is derived from the destructive power of Lake Superior and other violent waterways of the Canadian Shield and the emotionally painful tragedies caused by the unpredictable harshness of these bodies of water. Mishipizheu became the malicious element causing the lake to harm innocent people. From this initial birth of the monster, various tribes added on stories, which is not uncommon in myth-making. In fact, we can look at Mishipizheu as a good example of the possible evolution of a myth.

Hunting and gathering peoples often have animistic beliefs. Every natural element has a spirit, even stones and streams. Perhaps it was recognized early on that Lake Superior’s was not a gentle spirit. Lake spirits often became personified in world mythology. If you can imagine one being or creature controlling the lake, it is easier to deal with this entity through sacrifice and bargaining.

Once you create a god, spirit or monster that you can appease or cajole, then stories concerning the exploits of this being can be constructed. You can even think of the Greek myths this way. Zeus was once a sky and thunder spirit. Then, through story-telling, he morphed into the leader of a pantheon and a character in a rich mythological tradition.

Some of the stories concerning Mishipizheu even purport that he engaged in acts of benevolence, thus adding to his stature as a god and not solely a monster. In one story Mishipizheu was responsible for the primordial flood. In another story, we learn that swamps and quicksand are due to his slithering on the ground when he chose to take shortcuts from river to river.

In one particular mythological tale, Mishipizheu is referred to as the ancestor of all snakes, due to the belief that he was hit by lightning and shattered into thousands of those creatures. Another story tells of Mishipizheu the trickster. A shaman seeks a powerful medicine from Mishipizheu who happily complies. Unfortunately, the medicine only works for the shaman as he remains healthy while he watches his family and loved ones deteriorate and die around him.

Artists rendering of the famed Mishipizheu. (Australopithecusman / CC-BY-SA)

Final Verdict On Mishipizheu: Godly Extortion or Defender of Humanity

So is Mishipizheu more monster than god? What might tip the scales is that he does not engage in acts of benevolence. He is predisposed to cause harm continually and only will desist from this if he receives, basically, extortion money. But gods receive extortion money too, do they not? Did the ancient Greeks not placate Poseidon before sea travel? It seems that the gods like to be appreciated and remembered but are also quick to do good things for good people. They also might need to be coaxed a little into supplying help.

And it is not like the gods are a constant threat which has to be avoided. So the scales would seem to tip more toward monster in this case, yet one interested in mythology might ask whether a primarily malevolent “god” is possible. Or, dare we stretch and say that Mishipizheu was not at all malevolent but merely attempted, as well as he could, to steer humanity away from the world bought through copper, in an attempt to keep humanity living in a land of paradise.

Top image: The malevolent Mishipizheu monster-god of Lake Superior. Source: SJB1995 / CC-BY-SA

By Daniel Gauss

References

Johnston, B. 1990. Ojibway Heritage. Bison Books.

Treuer, A. 2001. Living Our Language: Ojibwe Tales and Oral Histories . Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Unwin, P. 2008. The Wolf’s Head: Writing Lake Superior . Cormorant Books

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

July 27th, 2021

July 27th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: