Between the years of 1630 to 1655, Giulia Tofana and her poison cartel were the primary facilitators of well over 600 deaths, by way of disgruntled wife, through their trademark poison known as Aqua Tofana. Some called her a serial murderer, and others called her a seductive assassin, but the truth was far more sinister.

Tofana was the leader of a poisonous network that spanned across Sicily, Naples, and Rome, providing a black market service highly in demand. Her underground empire included cunning women, back door apothecaries, crooked clergymen, and fortune-telling witches, solely dedicated to the sale and distribution of poison. However, after twenty successful years in operation, Tofana was finally caught for her crimes. Whether she was executed or let free is still a mystery.

In 17 th century Sicily, there were few options available for women who were either unhappy in their marriage or looking to inherit a fortune. One of the fastest and easiest ways for a woman to get rid of her husband was by means of poison. For those of the lower classes, poisoning an abusive husband could be seen as poetic justice. However, for those of the upper elite, poisoning was seen as a very sinister and untrustworthy act. All levels of society, however, were willing customers to Tofana’s cartel. So, what is worse? The abused wife wanting to poison her cruel husband, or the blackmarket poison provider making the gruesome concoction easily available?

Tofana and Her Criminal Magical Underworld

As the historian Mike Dash explains in many of his articles, the term “Criminal Magical Underworld” was first coined by Lynn Wood Molleneaur when exploring the black market community of witchcraft and poison crafting in early 18 th century Paris. In Molleneaur’s examination, this community network existed and operated in a fashion similar to contemporary organized crime. Though his findings discussed Paris, the description of its organization rings true when looking at the way Tofana controlled her poison business.

Though Tofana has been portrayed as evil and sinister, her original reputation, as discussed by the writer Hanna Mckennet, was that of a quiet “friend to all lower class women.” This was because the bulk of her clientele was primarily made up of abused women from the poor and working class, rather than the black widow gold diggers of the upper elites.

The most reliable accounts of Giulia Tofana’s reign can be gleaned from reading two 19 th century historians. The first is Allesandro Ademollo in his work I Misteri Dell’Acqua Tofina . The other is Salomene-Marino, in his article L’Acqua Tofana from 1881. These accounts claim she was born somewhere in Palermo, Sicily, around 1620 to Francis and Thofania Di Amado. Her mother is credited for creating the first variation of Aqua Tofana, used to poison Giulia’s father, before being imprisoned and executed in 1633 by way of public drawing and quartering. In the years after, historic accounts claim that Tofana did the same to her own husband. Soon after his death, she moved the operation to Naples with her daughter, Girolama Spara, before settling in Rome.

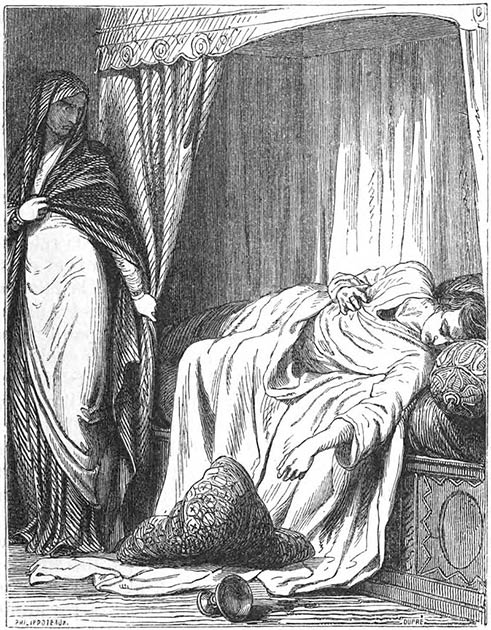

Giulia Tofana was not directly killing victims, but rather selling the poison so that others could do so. For the most part she catered to unhappy women trying to escape abusive relationships. ( Public domain )

Partners in Crime: Cunning Women and Holy Men

Giulia Tofana is said to have worked with Francesca La Sarda, who had initially worked with her mother. Her role was as a cunning woman, a term reserved for women who provided potions and lucky charms to the wealthy upper class. However, her time with Tofana was short-lived, as she was caught and tried and executed in February 1634. This was actually a few months after the execution of Tofana’s mother for the same crime.

Spara continued to work as a cunning woman among the upper noble class. At the same time, another assistant was acquired by the name of Giovanna de Grandis to cater to women within the lower ranks of society. Tofana also recruited the Roman Catholic priest, Father Girolamo of Saint’ Agnese in Agone, into her organization. Due to his brother being an apothecary, he was responsible for providing arsenic supplies in bulk. Many others soon joined her ranks. As Dash has mentioned in his work, Tofana’s organization may have employed well over 200 people, including:

“…wise women, astrologers, alchemists, confidence men, witches, shady apothecaries, and back street abortionists who between them told fortunes and cast horoscopes, sold love potions and lucky charms, curried toothache, and offered to dispose of unwanted babies and unwanted husbands.”

Though she was most famous for providing poison to those within her own network, she also offered many other black-market items for sale. Within these organizations, as Dash discusses, it was quite common for priests to secretly take part as black magicians. Their primary services included blessing ingredients, concocting love potions , and acting as middle men in the sale of all forms of black market poisons, charms, and books for communities dabbling in magic or fortune-telling, those with unwanted pregnancies, or even wealthy people looking for discretion in their illegal serum purchases. Tofana’s network also provided popular magic merchandise, ranging from absurd anomalies such as magic wands, grimoires, and incense, all the way to sexually alluring items such as love potions, breast milk, and dried menstrual blood.

The Criminal Networks of Magic and Alchemy in 17th Century Europe

Throughout every large 17 th century European city, there was always some form of criminal magical underworld in operation. As Mckennet explores, these networks would contain alchemists, apothecaries, secretive priests, and fortune tellers. Tofana’s network was no different. If you were to exclude Aqua Tofana from her list of potions and merchandise, most of her catalogue was actually beneficial for many. In fact, the majority of these gangs provided ancient herbal remedies to offer alternative treatments for ailments that priests and doctors simply could not cure.

Most of the services provided by Tofana’s so-called cunning women, such as Francesca la Sarda, provided insight into an ancient magical tradition that had been kept underground in Europe since the rise of Christianity. Such information about ancient magical ointments and potions not only preserved age-old European methods in proto herbal medicines, but also helped maintain intrigue among eager customers willing to purchase fortune-telling sessions, remedies for headaches and energy, and in some cases liquid medicinal options for unwanted pregnancies.

The ulterior motive, of course, to providing these seemingly harmless products was to gain insight into the marital situation of her clients. After all, poison was Tofana’s primary commodity. If women were brand loyal to her other items, then perhaps they would be interested in a final solution to a potentially lousy marriage. A solution that would require only the best of poisons. But, what made it so effective?

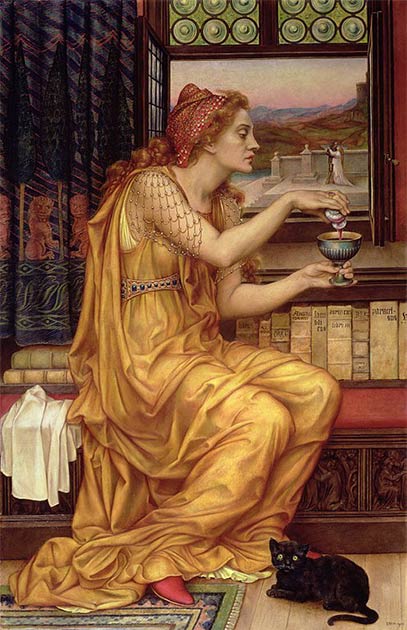

The story of Giulia Tofana and her trademark Aqua Tofana is entangled with the criminal magical underworld which existed throughout Europe. The Love Potion by Evelyn De Morgan. ( Public domain )

Tofana and her Trademark Aqua Tofana

According to Dash, “Aqua Tofana was credited with what amounted to supernatural powers and blamed for hundreds of agonizing deaths.” This concoction, which was originally created in Palermo, Sicily, by Tofana’s mother, was said to be tasteless, scentless, and the effect was to mimic that of someone dying of the common cold. The base ingredients were arsenic, lead, antimony, and mercuric chloride. Because of the era, in which sudden death was commonplace, the poison was undetectable by surgeons when performing their autopsies as it was indistinguishable from natural causes.

Mkennet describes Aqua Tofana as inducing “weaknesses and exhaustion followed by symptoms of stomach aches, extreme thirst, vomiting, and dysentery.” Mkennet continues to explain that all that was needed to kill an unsuspecting individual was six drops. In other accounts, what made this poison so effective was its ordinary appearance, similar to water. Known also as Manna di San Nicola, the poison could be conveniently stored in an average woman’s makeup container, making it easy and accessible for anyone administer it to their unsuspecting victim.

Its effectiveness and popularity were so high that even after the demise of Tofana’s gang the name became an infamous term for any subtle, slow-acting poison that was untraceable by any surgeon. Aqua Tofana was sold exclusively to women, from every rank of society, by way of Tofana’s secretive network of fortune-tellers and cunning women. As Mkennet explains, it was advertised as if it were a “face cream for any woman looking to appear beautiful and single again.” At the height of its popularity, and with an active network stretching from Sicily to Rome, it appeared that Tofana would expand throughout Italy. However, Tofana’s empire was about to come to an end.

Fall of the Poison Empire

In 1650, a young woman attempted to poison her husband with Aqua Tofana. She failed in her attempt, resulting in her husband angrily beating her until she confessed to purchasing poison through Tofana’s network. This in turn lead her to be delivered to the provincial authorities for further torturous interrogations. She finally admitted to the act, leading to an investigation into Tofana’s network. As Mkennet’s article discusses, Tofana went into hiding and was granted sanctuary in a church where she continued to make poison and distribute it through a new network of nuns. However, rather than it being used on unsuspecting abusive husbands, this time it was used to poison the local water supply.

It was only then that Tofana was finally turned in to the authorities, whereby she was tortured and confessed to the death of over 600 men between 1633 and 1651. It is said that in 1651 Tofana, along with her daughter Spara, forty of her customers, and six other assistants, was executed in Campo de’ Fiori in Rome. But, is this how she really died?

How Did Tofana Really Die?

Over the last four hundred years, several accounts have questioned Tofana’s demise. Both Mkennet and Dash describe alternative accounts related to her death, ranging from her having never being arrested but dying of natural causes in 1651, to accounts that claim she was actually executed in 1659, 1709, and unbelievably in 1730. If the last date is correct, it would mean she was well over 100 years old when she died.

All the accounts however agree on one thing: by the 1650s, Tofana was no longer operating as the leader of her network. Dash alludes to the fact that before the raid, her daughter Spara had taken over the network and moved all operations to Rome in 1658. There she remained undetected and protected by her many connections to wealthy widowers and noblemen. However, even this was short-lived, as both Spara and Grandis were eventually caught and publicly hanged in July 1659. The only survivor appears to have been Father Girolamo, who was exempt from prosecution.

Though members of her network were rounded up in 1659, many others fled to Rome, where Aqua Tofana continued to be produced. Though there was nobody to carry on her network, her recipe lived on in every apothecary shop throughout Italy. The potion continued to be created and was infamously associated with the death of Mozart many years later. The name lived on for several hundred years, and became synonymous with any slow-acting poison able to kill someone within three days. Whether the ancestors of Tofana continue to create this poison in secret, or whether her mysterious criminal magical underground indeed continues to thrive under the protection of political elites and a selective group of Catholic priests, one fact remains true: Poison was and is always in demand.

In 17 th century Italy, the poison, known as Aqua Tofana or Manna di San Nicola, was kept by unhappy wives alongside perfume and lotions, almost as a way of cultivating the fantasy of someday being free from their husbands. ( Public domain )

Why Is Poison So Popular?

In the modern era, poison remains the method of choice for female serial killers due its subtlety and ability to fool forensic experts. Poison is also very discrete, allowing killers to move their contraband easily from one place to another. As mentioned by Vronsky, the most common type of female serial killer is known as a black widow, with 85% of serial killers fitting the bill. Their most common victims are either husbands, lovers, or even their own children, with the objective of attaining wealth, land, or titles by way of inheritance. When the aim is safety and security, people will go to any length to achieve it.

However, Giulia Tofana doesn’t fit the profile of a regular serial killer. For one, poison was not her only product. She provided a plethora of merchandise and services that other channels could not offer. She was also not directly killing victims, but rather selling the poison so that others could do so. After all, the majority of her clients were, in fact, abused housewives of the lower working class, and for the most part she catered to unhappy women trying to escape abusive relationships. Additionally, as Mckennet discusses, in 17th century Italy there were very few options for women in the first place. Besides marriage, options involved sex work, becoming a nun, or a servant girl. Within those choices, marriage was often contractual and loveless.

Tofana provided not only the whimsy of 17 th century dark arts in the form of trinkets and charms, but also the fantasy of killing ones husband and running away. In most cases, women bought the poison as a novelty item to keep alongside their perfume and lotions, almost as a way of cultivating the fantasy of someday being free from their husband. But they never actually went through with the act. The fantasy remains as appealing as ever, much like the idea of the tall, dark stranger arriving to sweep you off your feet and take you away to a better future.

Top image: Giulia Tofana was a 17 th century leader of a poison cartel responsible for over 600 deaths thanks to her trademark poison Aqua Tofana. Source: Public domain

By B.B. Wagner

References

Dash, Mike. 2015. Aqua Tofana: Slow-poisoning and Husband-Killing in 17th century Italy. 6 April. Available at: https://mikedashhistory.com/2015/04/06/aqua-tofana-slow-poisoning-and-hu….

Dash, Mike. 2017. “Chapter 6 – Aqua Tofana.” In Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance History of Toxicology and Environmental Health, by Philip Wexler, 63-69. United Kingdom: University of Cambridge Press.

Mkennett. 2020. Meet Giulia Tofana: The 17th-Century Professional poisoner Said to have killed 600 men. 1 June. Available at: https://allthatsinteresting.com/giulia-tofana.

Salomone, Marino S. 1881. L’acqua Tofana, Nuove Effemeridi Siciliane. Vol. 11.

Vronsky, Peter. 2004. Serial Killers. The Method and Madness of Monsters. Berkely.

Related posts:

Views: 1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 17th, 2020

August 17th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: