Fans of the supernatural may have noticed a curious line in William Peter Blatty’s book The Exorcist. While talking about Satanism: “Well, there’s William Stumpf, for example…a German in the sixteenth century who thought he was a werewolf”. STOP…you can Google it later! Although this bestseller was a work of fiction the actual historic source of this reference was a curious 16-page pamphlet published in London in 1590 and later rediscovered in 1920, by occultist Augustus Montague Summers.

After offering advice to werewolf hunters on how to best dispose of a captured beast, the pamphlet describes the dire crimes of a wealthy German farmer called Peter Stumpp (sometimes Griswold). Born in the village of Epprath in the Electorate of Cologne in the mid-16th century. Stumpp was said to have been named after having had his left hand cut off, leaving only a stump, in German “Stumpf”. In Germanic mythological systems, which underpinned laws and court rulings, it was held that if a werewolf’s left forepaw was cut off, the same injury appeared on the man. Thus, Peter was a werewolf. Obvs!

Stories say that Peter Stumpp was an insatiable, bloodsucking werewolf. ( danielegay /Adobe Stock)

The 1590’s pamphlet reads like Gary Brandner’s The Howling novel being clashed with Tom Harris’ Silence of the Lambs. It provides trial notes and witness statements which can be found recorded in other publications, indicating that the story of Peter Stumpp’s execution is true, in every gut-wrenching part. The private diaries of Hermann von Weinsberg, a Cologne alderman, also covered this case and it was detailed in several broadsheets printed in southern Germany, which all convey identical versions this weird and gory tale. What you are about to read actually happened, and it is at this stage of my story I have to advise readers of a sensitive nature to press the back button. Seriously. This next bit is quite simply – messed up.

The Trial of a Cannibal

In 1589, Peter Stumpp was arrested and formally accused of being an “insatiable bloodsucker” and evidence was provided that he had “gorged on the flesh of goats, lambs, and sheep, as well as men, women, and children for over 25 years.” Facing torture, Stumpp then confessed to having murdered and eaten “fourteen children and two pregnant women”. You would have thought that Peter would have stopped there, while he was relatively ahead, but no, he verbally declared that he “extracted fetus’ from the pregnant woman’s wombs” and “ate their hearts panting hot and raw.” He also confessed to having regular sex with his daughter and to having had intercourse with a “ succubus sent to him by the Devil.”

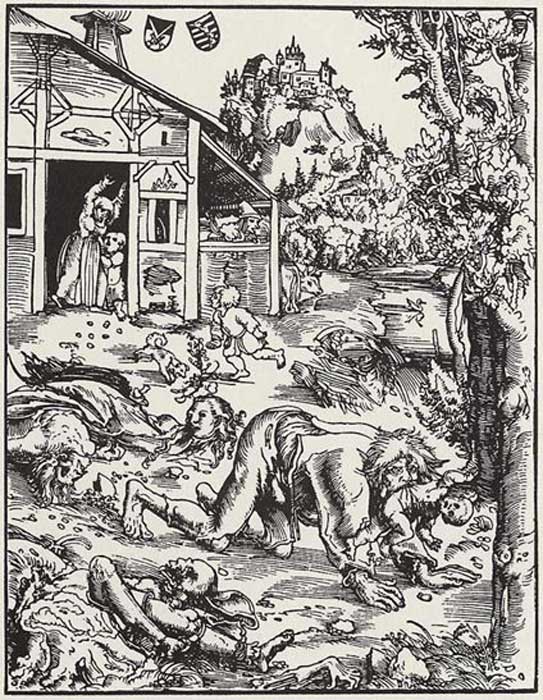

Woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1512, of a werewolf ravaging a town and carrying off babies. ( Public Domain )

Just before being stretched on a rack, Stumpp confessed to having had practiced black magic since he was twelve years old and said the Devil had forged, and given to him, a magical belt enabling him to metamorphose into “the likeness of a greedy, devouring wolf, strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body, and mighty paws.” When the belt was removed, claimed Stumpp, he would transform back to his human form.

After the trial an extensive search was made at Peter’s farm for the magical werewolf-belt but nothing resembling it was ever recovered.

Stumpp was finally put to death on October 31, 1589, in an extraordinarily violent manner, similar aesthetically to a scene from the Saw movie franchise. Having been strapped to a wooden wheel “flesh was torn from his body in ten places, with red-hot pincers, followed by his arms and legs.” Then his limbs were broken with the blunt side of an axehead, to “prevent him from returning from the grave,” before he was beheaded and burned on a pyre.

His daughter and mistress were flayed and strangled and burned along with Stumpp’s body. As a preventative measure against similar wolfish behavior, the torture wheel was erected on a pole with the figure of a wolf on it, topped by Peter Stumpp’s severed head.

Composite woodcut print by Lukas Mayer of the execution of Peter Stumpp in 1589 at Bedburg near Cologne. ( Public Domain )

The Hidden Political Agenda of the German Werewolf Hunters

A detail given in this story is found to be inconsistent with the historical facts, suggesting there is a hidden layer beneath the surface story of Peter Stumpp, the werewolf. The 16-page pamphlet and the German broadsheets all noted the attendance of “members of the aristocracy” at Stumpp’s execution “including the new Archbishop and Elector of Cologne”. This single fact suggests the presence of a hidden motive.

It might be relevant that the block of years in which Stumpp was said to have committed his crimes (1582-1589) were marked by internal spiritual and political warfare. The Electorate of Cologne was in upheaval upon the introduction of Protestantism by the former Archbishop Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg. Stumpp was an early convert to Protestantism and fought in a war which historians claim brought uncontrolled violence out of soldiers on both sides, resulting in an epidemic of the plague.

In 1587, the protestants were finally defeated and the new lord of Bedburg – Werner, Count of Salm-Reifferscheidt-Dyck made Bedburg Castle the headquarters of his Catholic mercenaries who were determined to re-establish the Roman faith. Stumpp’s werewolf trial may have been performed to, a tad more than gently, persuade the remaining Protestants to sign up to Catholicism.

It was unlikely that any of Germany’s elite would have attended a regular werewolf or witch trial – and they were regular. It is most likely the case that having drawn up Stumpp’s alleged, and truly outrageous crimes, the elite constructed a popular public spectacle, and with assured visibility to the public at large, the nobility mounted their rides and attended the disembodiment of a werewolf – a protestant scoundrel – an archetype of anti-Catholic spiritual darkness. It can be argued that never a public relations stunt since has matched the uniqueness and sheer morbidity of the execution of Peter Stumpp, the German werewolf.

Top image: A werewolf in front of a full moon. Source: CAA-digital /Adobe Stock

By Ashley Cowie

Updated on October 27, 2021.

References

Anon. A True Discourse. Declaring the Damnable Life and Death of One Stubbe Peeter, a Most Wicked Sorcerer. London, 1590. (original English version).

Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. p. 165

Homayun Sidky, Witchcraft, Lycanthropy, Drugs, and Disease. An Anthropological Study of the European Witch-Hunts. New York 1997, pp. 234–238.

Peter Kremer, “Plädoyer für einen Werwolf: Der Fall Peter Stübbe”, in, Ibd., Wo das Grauen lauert. Blutsauger und kopflose Reiter, Werwölfe und Wiedergänger an Inde, Erft und Rur. Dueren 2003, pp. 247–270.

Wagner, Stephen. “The Werewolf of Bedburg” .

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 28th, 2021

October 28th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: