“Flamma, secutor, lived thirty years. Fought thirty-four times, won twenty-one times, stood to draw nine times. Won a reprieve four times. Of Syrian extraction.”

An eroded inscription on an ancient tombstone in modern-day Sicily is all that remains of the great gladiator Flamma. Historians are left to fill in the gaps. Flamma (the flame) was famed, franchised, and celebrated in every game he fought. Even when he was defeated and called for a reprieve, he must have carried immense charisma to be blessed by the crowd with the gift of missio, the act of mercy for a gladiator’s life. One aspect made him unique among the gladiators who have been remembered by history: Flamma is the only gladiator on record to have won his freedom four times, and turned it down. In the end, he died at the age of thirty in the arena.

It appears that Flamma had only one wish: to die in the arena to the sound of the roar of his beloved crowd. He had no friends except for an honored combatant by the name of Delicatus, who cared enough to pay for his tombstone. With a life so glorious, two mysteries incite curiosity: where did he come from before his gladiatorial enslavement and why did he choose never to be free? The answers may lie in the history of Syria and in what we know about gladiator life within the arena.

Flamma the Revolutionary: The Likely Story

Between 66 AD to 145 AD, Jewish slaves were a very common commodity within gladiator schools. Due to continual conflicts with Jewish populations in Judea, Cypress, Egypt, Macedonia, and Syria, there was no end of persecuted Jews being captured and subsequently trained. Even then, many of those who were rejected were sent to die as noxii (the unwanted). Flamma may have been a Jewish Syrian who was captured at a young age and sent to Rome, after proving himself worthy in the arena. Though this is a working hypothesis, there are several historical factors that support this possibility.

Flamma’s epitaph has been dated to be from some time in the second century AD and it claims he was of Syrian extraction. If this is true, then Flamma’s past may have been quite challenging, especially due to the violent history between Rome and its subduing of several Jewish revolts in Judea and Syria. Under the reign of Emperor Hadrian, further tensions between the people of Judea and Roman-occupied forces ensued.

Shi’ mon Bar Kokhba was a Judean revolutionary who rebelled against the Roman, creating terror in Rome. ( Arthur Szyk / CC BY-SA 4.0)

It appears that the final spark for unrest within the region had to do with the construction of the Roman colony Aelia Capitolina on top of the ruins of Jewish Jerusalem. In the first years of rebellion, Shi’ mon Bar Kokhba defeated the provincial governor Quintus Tineius Rufus, leading to his untimely disappearance from history in 132 AD. This led to Bar Kokhba taking control of the Judea Province, attaining both titles of Nasi (prince) of the region and Messiah to his followers. Bar Kokhba’s success reached the floors of Rome, creating terror and forcing Emperor Hadrian to order the immediate dispatch of six legions into Judea.

After four years of hard fighting, the Bar Kokhba’s resistance was finally thwarted. Shortly after the conflict, in an attempt to demoralize the people of Judea, Hadrian renamed the territory: Syria Palaestina. As mentioned by the historians Boatright et al., the damage done to the region due to nonstop combat resulted in the deaths of 580,000 Jewish people, and the destruction of 50 Jewish outposts and 985 Jewish villages. A significant number of Jewish victims died from disease and starvation during the battle. Many of the remaining Jews were then sold into slavery.

Flamma would have been fourteen years old at the beginning of the conflict. He may have been present in one the cities bombarded by Roman catapults. He could also have witnessed the older males of his family partaking in the rebellion, and perhaps he even took part in fighting the legions of Rome. At the end of the revolt, he would have been seventeen years of age: having borne witness to the erasure of his culture, watched his entire family die, and seen his homeland turned into ruins, all at the hands of the Romans. If he were a captured as a rebel, he would have been immediately sent away after the conflict to be a prisoner of war and expected to die in the gladiatorial arena, alongside many other Jewish prisoners. The execution of prisoners of war via gladiator games was common, especially in the second century AD.

However, this is merely one possible theory regarding his life before the ring. Though it is the author’s opinion that he was most likely a Jewish survivor sold into slavery, it is still just a theory. There are many reasons why an individual would be sold into slavery. What if Flamma was actually a defecting Roman auxiliary legionnaire?

Another theory as to Flamma’s hidden history is that he was an auxiliary legionnaire who could have been sent into slavery for insubordination. ( Barosaurus Lentus / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Flamma the Roman Auxiliary Legionnaire: The Alternative Story

Returning to the Bar Kokhba revolt , one of the most famous legions that were dispatched to quell the rebellion was the Legio III Gallica of Syria. Along with the reputation of being a war-hardened legion that had faced many revolts in both Judea and Syria proper, they also contained a large auxiliary force of young men wishing to someday become Roman citizens. Auxiliary forces were very common, especially in fighting against Shi’ mon Bar Kokhba . As mentioned before, Flamma would have been sixteen or seventeen by the last year of the conflict, making him eligible to enlist.

Flamma may have been a first-year auxiliary legionnaire for Legio III Gallica, which was posted in Syria. He would have lived during the time of Hadrian and would have been a survivor of the revolt of Bar Kokhba. If he had been insubordinate, he would have been sent away to slavery for disobeying a Roman commander. Perhaps, he was not ready to enact atrocities against villages in Judea, resulting in his desertion. If this were the case, and if he were caught, it would mean he was then sold into slavery. As an auxiliary deserter he would forever be marked as untrustworthy and a disgrace fit for death in the arena.

Flamma the Gladiator was revered by the Roman people for his feats in the arena. This 1872 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicts the power of ancient Roman crows in deciding the fate of defeated gladiators, with verso pollice, or “with a turned thumb”. ( Public domain )

Adoration of the Roman People: Becoming Flamma the Gladiator

Whichever theory one wishes to believe, the result was the same. At the age of seventeen he entered the arena as a slave awaiting death, only to survive and attain the love of the Roman people. With this single act, his past life faded into oblivion. In the arena he was reborn as Flamma.

Before he could perform his epic battles against other skilfully trained professionals, Flamma would have begun his training in the lowest ranks of the gladiators. If Flamma was a Syrian Jewish prisoner of war, he would have begun as a gregarii, whose members were expected to die in groves. Most would be grouped with other prisoners of war and forced to fight each other to the death for the amusement of the crowd. Though there were little chances of survival for the gregarii, it was indeed possible to come out the supreme victor. If this occurred, they would be showered in praise by the crowd impressed by their valor.

Flamma most likely came from this rank. The unlikeliness of survival explains why he was very popular with the crowd. His luck in the first round may have offered him the opportunity to be properly trained to complete in other levels. Upon his first entry into the gladiator school, he would have been segregated to a specific group and class, and training at gladiator school would have been relentless.

According to Matyszak’s book, several classes of gladiators existed. Of the lower groups, Flamma may have been either a damnati ad gladium, which offered little or no future of survival, or a damnai ad ludos , which had a fighting chance to live. Both were forms of capital punishment. These beginning classes of slaves were essentially convicts sentenced to death in the arena. Eventually, after proving himself at the next level, he would have been trained with a specific skill set for a proper gladiator game.

In the arena he was reborn as Flamma. ( Public domain )

On Flamma’s epitaph, it mentions that he was a secutor, or chaser. This term was given to a heavily armored combatant armed with a hefty scutum shield, a gladius sword, and wearing a manica on his right arm. His specialty would be fighting against a the retiarius gladiator, or net man, who carried little to no armor but was armed with a net and trident.

The training regimen and food would have been intense and abundant. The routines that gladiators were forced to go through were strenuous. Most trainers (known as medicus or magisters) would force them to train and practice to the point of fatigue. But even though their training was never-ending, so were their breakfasts, lunches, and dinners: Due to their quick metabolisms, they needed constant food.

As mentioned by Coughlan from the BBC, the primary gladiator diet consisted of barley, wheat, fruit, vegetables, and beans. Meat was rare and came from either purchasing game from local hunters or from the rotting exotic meats of beasts killed in the arena. Though gladiators may have burned away a majority of their excess fat, it was often acceptable for gladiators to carry a bit of extra weight. The extra fat acted as a cushioned barrier for bruising, as well as a pleasing spectacle of gushing blood from a non-lethal cut over a fat belly.

All this training would pave the road to his success. Flamma would go on to fight and win 21 games. However, he also lost four times, which begs the question: How was he still alive?

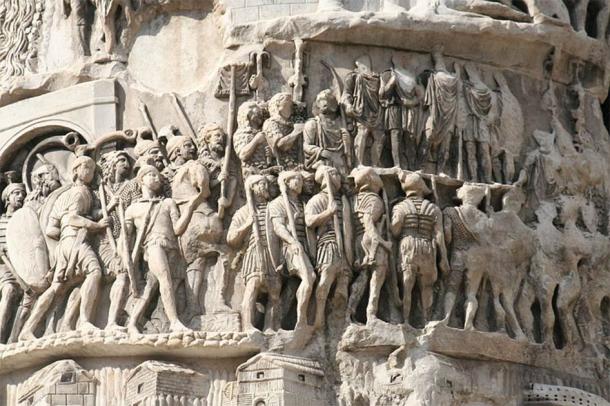

Roman relief showing gladiators fighting. In the top image a standing secutor fights a retirarius lying on the ground, while below another secutor is in action. ( Following Hadrian / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Staying Alive: Fighting to the First Slice

The greatest misconception about gladiators is that they fought to the death. More often than not, gladiators would fight to the first slice. The reason for this was that gladiators were a very expensive investment, as proper training cost time and money. To waste a perfectly good gladiator was excessive and frowned upon. Additionally, the majority of their games didn’t necessarily happen in the arenas of Rome. In many cases they were held in smaller venues such as festivals, ceremonies, and funerary blessings. It was only in the Imperial arenas, where the emperor called for special celebrations once a year, that the gathering of the gladiator combatants took place.

In the case of Flamma, he may have lost his battles in lesser arenas and ceremonies, possibly explaining why he maintained his life. Other sources, such as the work of Coleman, state that the love of a gladiator’s bravery and charisma could explain who Flamma lived past his four losses. As Coleman states:

“…Flamma fought a remarkable thirty-four engagements, winning twenty-one and drawing nine. Hence, he was defeated in little more than ten percent of fights over his career, which may be why he admits to these four instances of what was technically defeat…”

The perplexing aspect to Flamma’s story is that he earned his freedom four times, only to turn it down. Why would someone reject the offer of freedom from what was basically a life of slavery?

Flamma chose death in the arena over freedom. But why? ( Public domain )

Life After the Arena: Choosing Slavery Over Freedom

Besides his unknown history before life in the ring, one of the greatest mysteries about this famed gladiator , and one which has puzzled historians for centuries, is why he refused freedom not just once, but four times. With 34 fights under his belt, he would have been a very successful man in his prime should he have decided on a life of freedom. Instead, he decided to keep fighting until his death at the age of 30. While the concept of a life of fighting until death may appear dismal to most people in the 21 st century, a successful gladiator lived significantly well, especially during the second and third century in Rome.

Gladiators could keep any gifts and money they were awarded, and if a gladiator was lucky enough to continue to win, as Flamma did, he could have invested in marketplace opportunities, or even in bets between himself and other gladiators. Although the life of a gladiator could be unforgiving, some opportunities were bestowed in the ludus, or gladiator school, that would never be guaranteed in regular civilian life. Within the training grounds there was no fear of starvation, there was constant medical assistance and shelter was guaranteed. Additionally, gladiator brotherhoods and fighting guilds developed to assure a proper burial and there was even a retirement option for those lucky enough to live through their fighting prime.

Retired gladiators were often hired to perform at special ceremonies or as male prostitutes to wealthy patrons. ( Public domain )

Once free, most gladiators could be bribed out of retirement during spectacular games organized by emperors. One such case occurred when Emperor Tiberius offered 100,000 sesterces for any aged gladiator to return to the ring for one more game. Given the limited options available to retired gladiators, such an endowment would have been significantly appealing. Retired gladiators were customarily hired for special ceremonies to promote small shops and aid in the blessing of temples, as their notoriety and fame would be able to draw a good crowd. Profits from such events would be paid to those able to perform in ceremonial practices of these festivities. One of the final obligations were for the former lanistas of retired gladiators to bring them along with their rudis, or wooden sword of freedom, to give motivational speeches to younger gladiators starting out in their training.

Though the retired life of a gladiator, as described above, may appear gentle and respectful, it actually was rarely the case. More often than not, retired gladiators would end up in the legions as enlisted soldiers or bodyguards to wealthy patrons. What was even more demoralizing to these killer performers was that their greatness was swiftly forgotten and overshadowed as newer and more entertaining gladiators took to the arena. In the end, all that was left was a simple headstone, paid and bought by the brotherhood guild they had paid into over the years when they were active.

[embedded content]

When it came to Flamma, his situation may have been more complex. His options during the second century were limited: becoming a bodyguard, a male prostitute for wealthy patrons, a gladiator trainer, a freelance performer, or a potential lanista himself. Many of these could have been seen as depressing and shameful. If Flamma was indeed a 17-year-old survivor of the Bar Kokhba revolt, his homeland had been destroyed, and should he return “home” as a slave gladiator, no clout or respect would await him amongst his Jewish brethren. If he had defected from the legion, on the other hand, his shame would be remembered and he would always be treated like a traitor.

With no motherland to return to, and his savings dwindling due to bad management from exploitative lanista’s, Flamma would have been left with nothing. Perhaps his was why he refused to retire, preferring to die a glorious death fighting rather than face the reality of his past and an uncertain, yet dim, future outside of the ring.

Top image: While little is known about Flamma the gladiator, the details we have give rise to questions about his origins and the quality of life for a gladiator during his era. Source: zamuruev / Adobe Stock

By B.B. Wagner

References

Adhikari, Saugat. 20 November 2019. Top 10 Famous Ancient Roman Gladiators . Available at: https://www.ancienthistorylists.com/rome-history/top-10-famous-ancient-roman-gladiators/

Boatright, Mary T, Daniel J Gargola, and Richard J.A Talbert. 2004. “Institutionalization of the Principate Military Expansion and It’s Limits, the Empire and the Provinces (69-138)” in In the Romans From Village To Empire a History of Ancient Rome From Earliest Times To Constantine , by Mary T Boatright, Daniel J Gargola and Richard J.A Talbert, 376, 386, 398. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carter, Michael. 2003. “Gladiatorial Ranking and the “SC de Pretiis Gladiatorum Minuendis” (CIL II 6278 = ILS 5163).” Classical Association of Canada 57: 83-114.

Coleman, Kathleen M. 2019. Defeat in the Arena . Cambridge University Press 66 (1): 1-36.

Coughlan. 22 October 2014. Gladiators were ‘mostly vegetarian’ . Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/education-29723384#:~:text=The%20bones%20revealed%20that%20the,in%20front%20of%20Roman%20audiences

Grossman, Lt.Col. Dave. 1995. On Killing . London: Little, Brown and company.

Hanel, Rachel. 2007. Gladiators. Creative company . Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=fUoLHH7dFLUC&pg=PA31&lpg=PA31&dq=flamma+the+gladiator&source=bl&ots=BC1ZmFoA4f&sig=ACfU3U2jCCINivDXGhegDlWqO383MBS21g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiPhbfAsP3lAhVTHjQIHYkCANo4ChDoATAHegQIChAB#v=onepage&q=flamma%20the%20gladiator&f

Hope, Valerie. 2000. “Fighting for Identity: The funerary commemoration of Italian Gladiators” in Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies . Supplement (Oxford University Press) 73: 93-113.

Mancini, Mark. 19 August 2020. 7 Astonishing Roman Coliseum Fights . Available at: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/53408/7-astonishing-roman-coliseum-fights

Matters, Military History. 12 February 2015. Top five: Gladiators . Available at: https://www.military-history.org/articles/top-five-gladiators.htm

Matthews, Rupert. 2003. The Age of Gladiators: Savagery and Spectacle in Ancient Rome . New Jersey: Chartwell books, Inc.

Matyszak. 2014. Legionary: The Roman Soldier’s Unofficial Manual . New York: Thames and Hudson.

Matyszak, Philip. 2011. Gladiators The Roman Fighters Unofficial Manual . London: Thames and Hudson.

Poynton, J.B. 1938. “The Public Games of the Romans” in Greece and Rome . Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association. 7 (20): 76-85

Tex, Scipio. 21 June 2011. The Refs Are Killing Us: Gladiators Revisited . Available at: https://www.barkingcarnival.com/2011/06/21/the-refs-are-killing-us-gladiators-revisited

Varon, James. 24 March 2018. 10 Famous Ancient Roman Gladiators . Available at: https://historymonk.com/famous-ancient-roman-gladiators/

Whatdreamsmaycome.eu. 09 February 2017. Flamma the Barbel . Available at: http://whatdreamsmaycome.eu/2017/02/09/flamma-the-barbel/

White, Francis. 22 October 2014. Who was the most successful Roman Gladiator? Available at: https://www.historyanswers.co.uk/ancient/who-was-the-most-successful-roman-gladiator/

Related posts:

Views: 1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 31st, 2020

August 31st, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: