Today, Nicolaus Copernicus is hailed by many historians as the originator of heliocentrism, one of the first steps towards modern cosmology and away from the Aristotelian cosmology which had previously dominated Western thought. Copernicus is widely revered today, but his more radical ideas were not well received when his seminal work was first published. This is reflected in the fact that the location where he was buried was lost to history for centuries. This was the case until 2008 when a team of Polish scientists announced that they had finally found the last remains of Nicolaus Copernicus.

Nicolaus Copernicus Monument (by Bertel Thorvaldsen) in Warsaw, Poland standing in front of the Staszic Palace, the seat of the Polish Academy of Sciences. ( Belogorodov / Adobe Stock)

The Scientific Work And Life Of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus was born Mikolai Kopernick in the town of Torun in what is today Poland in the year 1473 AD. His father was a copper trader who died around 1483 AD, when Mikolai was only ten years old. After his father’s death, his uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, an official in the Catholic Church, took Mikolai and his siblings under his guardianship. The boy received a robust education, and his uncle envisioned a career in the church for his nephew. At the time, a position as a cleric or administrator in the church was a comfortable career, especially for those interested in devoting much of their time to learning.

Nicolaus Copernicus’ uncle Lucas Watzenrode, an official in the Catholic Church, took Nicolaus and his siblings under his guardianship after their father died. ( Public domain )

In 1491 AD, Mikolai was enrolled in the University of Cracow (also Krakow) where he learned among other things, Latin, mathematics, geography, philosophy, and astronomy. Astronomy at the time was studied by those who were expected to work in navigation, astrology, and other practical fields, or at least fields considered practical at the time. It was while he was at the University of Cracow that Mikolai took the latinized version of his name, Nicolaus Copernicus.

Nicolaus Copernicus completed his coursework at the University of Cracow around 1494 AD, though he did not formally receive a degree, which was common at the time. His uncle intended to set Copernicus up for a comfortable life by preparing him for a career in the church, so Copernicus went to the University of Bologna in Italy to study canon law in 1496 AD.

It is at the University of Bologna that Copernicus’ interest in astronomy appears to have begun in earnest. While in Bologna, Copernicus read the works of important astronomers at the time, such as Regiomontanus. He also lived in the home of one of the pre-eminent astronomers at the university, Domenico Maria de Novara. Copernicus took up the study of Greek, mathematics and astronomy alongside canon law. Copernicus also observed a lunar eclipse of the star Aldebaran in 1497 AD.

Copernicus’ growing interest in astronomy led him to give a series of lectures in Rome in 1500 AD. The year 1500 AD was considered a jubilee year and all devout Christians were encouraged to travel to Rome during that year. Copernicus’ lectures were addressed to scholars and pertained to mathematics and astronomy.

Copernicus returned to Frauenburg (the German name for Frombork, Poland) in 1501 AD to be officially installed as a canon at the cathedral. Although he had accepted the position of canon, he was able to convince his uncle and the cathedral chapter to send him to the University of Padua to obtain a doctorate in canon law as well as to study medicine. Although he studied law there and eventually received his doctorate from another Italian university, a major part of Copernicus’ motivation to return to Italy was to continue his studies in astronomy.

While in Padua, Copernicus studied both astronomy and medicine. At the time, astrology and medicine were intertwined because the stars were thought to affect the human body and physicians used astrology in their work.

Copernicus finished his doctorate in canon law in 1503 AD but received it from the University of Ferrara instead of Padua or Bologna. He then returned to Frauenburg to take up his duties as a canon. For much of the next few decades, he worked as a church administrator and, briefly, as a physician to his uncle Lucas Watzenrode, who was now the Bishop of Ermland, until his uncle died in 1512 AD. It was while working in these roles that he made many of his important astronomical observations.

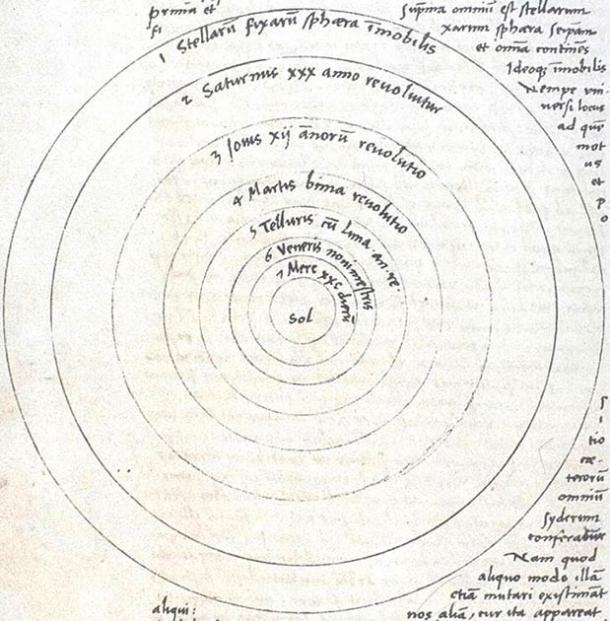

In 1514 AD, Copernicus wrote Little Commentary , a text that would become an introduction to his later work for which he is famous. Little Commentary outlined Copernicus’ cosmological ideas and mathematical work. The book represents Copernicus’ early work on developing the heliocentric theory.

Nicolaus Copernicus observing the heavens in this 19th century AD painting. (Jan Matejko / Public domain )

For The Next 30 Years Copernicus Fought Political Disruption

Over the next thirty years, Nicolaus Copernicus’ astronomical work was often interrupted by political events including church councils and wars. Also, in 1514 AD, Copernicus was asked by the Catholic church to participate in the reform of the calendar.

At the time, the Roman Catholic Church used the Julian calendar, first devised during the reign of Julius Caesar. By the 16th century AD, the calendar was no longer in phase with the annual motion of the sun. This affected knowing the date of solar-related astronomical events, such as the vernal equinox. Predicting the date of the vernal equinox was important because it was used to determine the date of Easter which was central to the entire Christian liturgical year. For this reason, the Church decided to reform the calendar at the 5th Lateran Council. It is not known whether Copernicus was involved in reforming the calendar, though it is known that he did not attend any of the council sessions.

A photographic copy of a mid-16th-century AD portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus by an unknown painter. (Craigboy / Public domain )

Copernicus finally started working on the publication of his theory in a work, which would later become known as De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, in earnest in 1539 AD with the help of a young professor from the University of Wittenburg, Georg Rheticus. Rheticus had heard of the famous old mathematician and desired to learn as much as possible from the man.

Rheticus came to Frauenburg in 1539 AD and ended up living with Copernicus for two years. While he was there, he urged Copernicus to finish working on De revolutionibus orbium coelestium . In 1541 AD, Copernicus gave Rheticus the draft of his finished manuscript and Rheticus returned to Wittenburg. While back at Wittenburg, Rheticus sought to get the book printed. Eventually, Andreas Osiander, a Lutheran theologian in Wittenburg, agreed to print the book. He had already printed several books on mathematics.

Cropped image of page 9 of Nicolaus Copernicus’s famous De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium manuscript published by and tampered with by Osiander, the printer. ( Public domain )

When Osiander printed the book, however, he apparently found Copernicus’ ideas to be too controversial. In the printed copy, he left an unsigned note at the beginning of the book stating that Copernicus’ heliocentric model was for calculation purposes only and was not meant to represent an actual depiction of the universe. This was published without permission and did not reflect the intent of Copernicus who does appear to have meant it to be an actual model of the universe. This enraged Rheticus, who, according to one account, crossed out the note with a giant red X when he first received his copy.

The book, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium , was published in 1543 AD. According to legend, a copy was sent to Copernicus on his death bed, right before he died from the effects of an earlier stroke.

Some believe that Osiander was acting dishonestly and was obstructing scientific progress when he wrote the note without permission. Others believe that it was because of Osiander’s added note that Copernicus’ ideas were accepted at all and not immediately denounced as heresy. Copernicus’ ideas challenged not just geocentrism, but the entire world of Aristotelian physics which had formed the basis of the Medieval understanding of the physical world.

In the Aristotelian worldview, everything was where it was because that was its natural place. Rocks fell to the ground because they belonged at the center of the universe, for example. Copernicus was suggesting that Earth was not at the center of the universe which would mean that a new explanation would need to be found for why things fell to earth. That new reason, gravity, was elucidated over a century later by Isaac Newton.

This is just one example of how the Copernicus’ model shook the late Medieval paradigm. In 1616 AD, Copernicus’ book was placed on the list of forbidden books, “pending corrections” by the Catholic Church. The book was not removed from the forbidden book list until Pope Benedict XIV took it off the list in 1748 AD.

In light of these facts, it is unsurprising that Copernicus’ burial location was lost to history. It was only over a century after his death that his ideas became widely accepted and led to the rise of modern astronomy and physics. Although he is considered a hero of science today, in 1616 AD he was a heretic with absurd ideas who was best forgotten.

Finding The Long-Lost Grave Of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus was not forgotten, but his burial place was. It was known that he was buried beneath the cathedral at Frauenburg, but the exact location of his remains was unknown for years. In the centuries since his death, many individuals and groups have attempted to find the grave of Copernicus, including Napoleon and the Nazis.

An additional factor that complicated the search for Copernicus’ grave was that the Frombork (Frauenburg) Cathedral was damaged in the intervening centuries when it was plundered by Swedish soldiers. It was damaged again during the Second World War.

Nonetheless, interest remained in identifying the remains of this famous scientist. Beginning in 2004 AD, a team of Polish scientists searched the Frombork Cathedral and found an assortment of skeletal remains. Most of the skeletal remains could not be identified. The team knew, however, that one of Copernicus’ main duties was the Saint Cross altar and suggested that he might have been buried near that altar.

The scientists searched the around the altar and found a skull. The lower jaw was missing but the skull had evidence of a broken nose. It was determined that the skull had belonged to an individual who had been about 70 years old, the same age as Copernicus when he died. They also produced a reconstruction of what the old man looked like while alive. He bore some resemblance to a self-portrait Copernicus had made of himself while at Padua.

The team also found DNA on the skull in the molars and were able to match the DNA with two nearby femurs. Although they were able to determine that the femurs and the skull came from the same person, they were unfortunately unable to find the remains of any of Copernicus’ relatives for comparison. This left them at an apparent dead end.

Another line of evidence, however, surfaced at Upsala University in Sweden. At the Upsala University library is a copy of the Calendarium Romanum Magnum , a star chart created around 1518 AD, which was used extensively by Copernicus to conduct his observations.

The Calendarium had been taken to Upsala when Swedish forces invaded Poland during the Second Northern War (1655-1660 AD). Many towns, castles, and churches were left in ruins and their contents were plundered. Among these plundered goods was the copy of the Calendarium belonging to Nicolaus Copernicus. The now famous star chart ended up at the university in Upsala where it sat for centuries. The star chart was known to have belonged to Copernicus which is probably one of the reasons that it was maintained.

It was examined by the astronomer Golan Hendricksson who found 9 strands of hair on the ancient star chart and these nine strands were submitted to a lab for analysis. Four of the strands of hair provided valid DNA results and two of them had DNA which serendipitously matched the DNA of the skull found in the cathedral at Frombork.

This was considered to be a match and the scientists published their findings in 2008 AD. The grave of Copernicus had been found. In May 2010 AD, the remains of Copernicus were given a proper burial in a memorial ceremony and interned once again at the cathedral in Frombork. This time, church officials blessed the remains of Nicolaus Copernicus.

Nicolaus Copernicus stamp issued in 1973 AD by East Germany or the DDR, which clearly shows that this scientist was a hero and not just in Poland! ( konstantant / Adobe Stock)

The National Hero Legacy Of Nicolaus Copernicus

Far from being considered a heretic or lunatic, Copernicus is honored today. In Poland, he is considered a national hero. Although his heliocentric model was not perfect and his cosmology was later replaced by that of Kepler and Newton, his model was the first step towards a modern understanding of the universe.

Copernicus, however, is not just honored for his ideas. During his life, Copernicus was known for being conscientious in fulfilling his duties to his country. Although many scientists are honored today for their ideas, not many of them are great role models in their personal conduct. Copernicus on the other hand, appears to have been a good personal role model as well as a good scientific role model.

Top image: Monument of great astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, Torun, Poland. Source: Lukasz Janyst / Adobe Stock

By Caleb Strom

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 30th, 2020

December 30th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: