NEW YORK — One of the all-time great satirical articles from “The Onion” begins with the headline “ACLU Defends Nazis’ Right To Burn Down ACLU Headquarters.”

It’s not totally fair; the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) does not defend violence, but they do vehemently defend free speech, such as the burning of flags and, yes, the rights for Nazis hold rallies. Most infamously, in 1977 the ACLU argued before the US Supreme Court for the rights of a group of Nazis led by Frank Collin to march through the suburb of Skokie, Illinois, which was home to a great many Jewish survivors of concentration camps. It was the ultimate test for strict believers in First Amendments rights, and still causes headaches today.

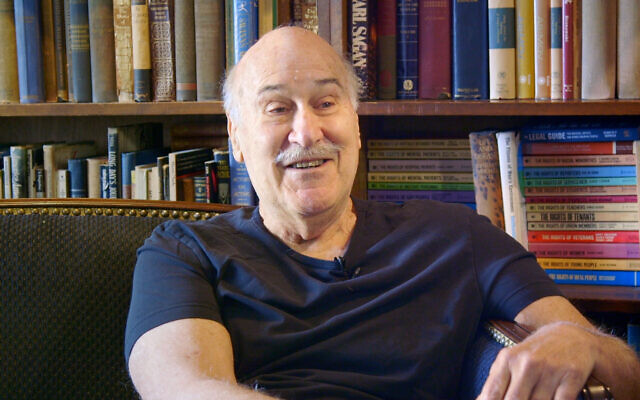

Ira Glasser, age 82, was the executive director of the national ACLU from 1978 to 2001, following a stint as the head of the New York Civil Liberties Union. While he did not initiate the group’s defense of the Illinois Nazis, it was one of the defining fights of his career. That’s a little weird for a Jewish guy who, after seeking career advice from then-senator Robert F. Kennedy, was dedicated to civil rights.

“Mighty Ira,” a new documentary being released as the ACLU turns 100, is a biographical portrait of the group’s longtime forward-facing leader. It is available to watch via virtual cinemas starting October 2.

Today, Glasser is a friendly octogenarian more eager to chat about baseball than take unpopular positions on drug legalization or hate speech. But for the decades he was in the fight… well, actually, he was always friendly. Even when sparring with his ideological nemesis William F. Buckley he did so warmly, and, indeed, the two men were quite close offstage.

The film jumps back and forth in time, with the Skokie case as one of its central topics. I’ve been familiar with the case for as long as I can remember, but I learned a few things. Though I knew Collin and his gang of repugnant, small-minded, diabolical Nazi worms (it is my constitutionally protected right to call them such things!) initially wanted to march in Chicago before moving to Skokie, I always thought they chose that suburb because of its large population of Jews, particularly Holocaust survivors. This is, in actuality, not the case. They wanted to go to any suburb, and petitioned many, but while the others simply ignored the request, Skokie was the one who turned around and said “No!”

Illustrative: American Nazi leader Frank Collin calls off the Skokie march in 1978. (public domain)

Among those saying no was Ben Stern, a concentration camp survivor who was one of the leading voices in the pushback. There is tremendous footage of him (and others, including Meir Kahane) saying “never again!” in this film, but also of Stern, who is still kicking at 99.

“Mighty Ira” is a troubling movie which initiates a war between your head and your gut. Any thinking person will understand the arguments the ACLU makes for defending Nazis. But it’s very difficult, for me at least, for that rationalization to transfer into action. (Action other than muttering, “oh, gimme a break,” that is.)

Nevertheless, Glasser remains a compelling and likable figure, and my chat with him was nothing but pleasant. Below is a transcript of our conversation, edited for clarity.

The Times of Israel: Thank you for taking the time to do this.

Ira Glasser: It’s no problem, I am an accomplished Zoom user by now.

Zoom isn’t so bad, actually, I’ve grown to like it, though you can’t do other things like you could with the phone.

Right, you can’t cook and Zoom. You can’t run to the bathroom and Zoom. But I almost never have a normal phone conversation anymore, only Zoom or What’sApp or FaceTime.

Tell me, Ira, because the people need to know: do you still have a landline telephone?

Yes, I do.

Good for you.

Of course, no one calls me on it. I only get robocalls, nonstop, which drive me insane.

This is a question for the ACLU. Do robots have a right to make intrusive telephone calls?

No. A robot has no rights! Nobody ever thought they’d hear me say something like that, but there you go. The people who are using the robot, they have rights.

Ira Glasser speaks in this still from ‘Mighty Ira.’ (Courtesy)

Got it, the programmer, yes, but the robot itself can go straight to the gulag. Let’s talk about this film. You seem like a fairly humble guy — how much arm-twisting did the producers have to do to get intrusive cameras into your life?

I spent 35 years being a very visible and controversial person. On one level I find this mortifying, but I have gotten used to it. When there is a project like this, there is, however, a peculiar kind of embarrassment that comes with it. Sure, it’s flattering, and your friends and grandchildren are excited, but I was always a pretty private person.

I may have worked 90 hours a week at the ACLU, but when I came home, that was it. I was with the kids, I was with my wife. I didn’t discuss issues around the dinner table. If I did a television debate with William F. Buckley, everybody in my world knew about it, but I didn’t watch it at home. I just taped it earlier! Only when my kids got older they would watch a 10-year-old video and be surprised at what I did.

This film took about two years to put together, but most of it, after the interviews, didn’t involve me. I mainly just talked in my apartment.

But they did take you out to where Ebbets Field used to be. At first it just seems like “ah, Ira Glasser loved the Brooklyn Dodgers” but then it builds to an interesting argument about how that place really was an incubator for your life’s work.

You have to understand that I wasn’t aware of it at the time. I was just a baseball fan who loved Jackie Robinson. I didn’t realize I was participating in a Civil Rights event. It was an accident of timing.

I grew up when society was rigidly segregated. Not just in the South by law, but in a place like New York City by custom. I was in a white Jewish neighborhood, where I never saw anybody Black — not in the stores, not in school, not on the street, not in the playgrounds. I never even saw anybody white who wasn’t Jewish!

New York was always religiously, ethnically, racially integrated as a whole, but it was a collection of very segregated ethnic neighborhoods. Only on the borders between those neighborhoods, which sometimes had conflict because of various prejudices and bigotries, was some integration. It was maybe more segregated than the South, where the laws requiring separation occurred because people were physically contiguous. In the North, you didn’t need those laws, because everybody was physically separated.

Ira Glasser returns to Ebbets Field in this still from ‘Mighty Ira.’ (Courtesy)

You mean because of the higher concentration, in a way, there were stronger barriers, stronger fences? Like, were it not for the geographical nature of New York we could have had a Jim Crow in the North?

Yes, that’s right. It was no less racist, it just didn’t require that mandated physical separation. So Ebbets Fields after Jackie Robinson was literally the only integrated public accommodation in the country.

It was the only place where a 10-year-old like me could go to a ballgame and sit next to a 35-year-old Black guy drinking a beer. And we were rooting for the same team, on the same side, and if something good happened we would jump up and slap each other on the back. Affectionate physical contact in those years, 1947, it couldn’t have happened anywhere else in the country. I called it an integration of the soul. I sometimes joke that if I had been a New York Yankees fan I would have turned out to be a racist.

I sometimes joke that if I had been a New York Yankees fan I would have turned out to be a racist

Years later at the ACLU I found so many co-workers from all over who were Dodgers fans, so I recognized that this actually was something significant.

My father is a little younger than you, but he grew up in Washington Heights. By proximity he should have been a New York Giants fan; the Polo Grounds was a short walk. But he and his father, who was a World War II refugee, would schlep an hour to Ebbets Field.

Of course. Later in life I would find people like an elderly Black woman from Alabama — and there were few women baseball fans then, because another way to keep women out of ordinary lives was to raise them not to care about sports — and she loved the Dodgers. You’d think how was this possible?

Jackie Robinson wasn’t just a ball player, he was a civil rights hero, but I had no conception of this when I was a 10-year-old.

Ira Glasser, right, speaks with Nico Perrino, who works at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, in a New York City subway in this still from ‘Mighty Ira.’ (Courtesy)

Let’s talk about another hero, Ben Stern. The film ends with him saying he loves you, yet for decades he looked upon you as a nemesis. Clearly, in the film, we see you have great respect for him — what was it like meeting him the first time? Were you aware of his work all these 40 years?

No, I didn’t know about him at all. I knew there were locals in Skokie who were the principal voices of opposition, but I was not in Illinois. I was dealing directly with the reaction in New York, and since there were more Jewish members of the ACLU in New York than probably anywhere, there was enough turmoil to keep me busy. When I became national head of the ACLU, I was very involved with Skokie, but I never met the principals, and never heard the name Ben Stern.

So let’s jump to a few years ago. A good friend of mine calls and says that he is close with a woman who made a documentary about her father, who is a survivor of seven concentration camps. He asks if I will watch it. I don’t know why he wants me to watch, as I am not an expert on the Holocaust or anything, but he is a friend, and I say yes.

I am watching and it is a very moving story, very emotionally jarring, as is any film on this topic, or a topic like lynching or slavery or what have you. But I’m thinking “I have seen 100 movies like this, why is he asking me to watch this?” Well, most of it is photographs of Ben Stern as a young man, but as he gets older he and his family move from Chicago, and ultimately to the suburb of Skokie.

Holocaust survivor Ben Stern, left, shows Ira Glasser his concentration camp tattoo in this still from ‘Mighty Ira.’ (Courtesy)

And then I just… I just sag in my chair. I’ve been retired for 15 years at this point. I do not want to do this again.

But I watch, and it deals with the Skokie controversy fairly. I learn that Ben Stern’s daughter wants to talk with me. She’s an avid civil liberties supporter, but doesn’t understand how we could defend these vermin. I tell her “defending vermin is what we do.”

I explain that the way they stopped the Nazis from marching first in Chicago, and then in Skokie, was they said that they couldn’t demonstrate in a park unless they posted a $300,000 insurance bond. The problem with that is that no insurance company would sell you such a bond, and this was the same mechanism by which towns in the South blocked Martin Luther King, Jr. And we had always gone and gotten them struck down.

A photo with Martin Luther King Jr. is displayed at the Take A Stand Center at the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center on October 26, 2017 in Skokie, Illinois. (AFP PHOTO / Joshua Lott)

In fact, the Skokie case started because the Nazi group wanted to be in the same park that the Martin Luther King Jr. Association, a Black civil rights group, was also demonstrating in at the time. The city got tired of dealing with all the demonstrations, so they made everybody post that kind of an insurance bond. So if you didn’t strike it down for one, you couldn’t strike it down for the other. I mean, that’s just the way law works.

She couldn’t understand how you couldn’t make an exception. In this case, you had Holocaust survivors, you had these guys with swastikas. I actually think it’s in the interest of Jews to have a strong First Amendment, because as a minority, they are more likely to be targets of government restrictions on speech than anybody else.

I actually think it’s in the interest of Jews to have a strong First Amendment, because as a minority, they are more likely to be targets of government restrictions on speech than anybody

I ultimately wrote a blurb for the film, and then a review on her request. I was happy to do it, once I figured out a way to say something useful that didn’t compromise my own position. This led to me appearing on some panels after screenings out in California.

I flew there, and Ben Stern is a little man. He was 95-years-old then, about to turn 99 any day now. He gets out of the car, and he’s feisty. He smiles, he shakes my hand, and he says “we aren’t going to agree! But we are going to be friends!”

Then we sit in his kitchen and talk for two hours. He talks about how some in Skokie said “just sit in your house, pull down the shades, ignore them, just wait,” and how that is exactly what they told him in Poland, so he wasn’t going to do that.

Which, in a way, is exactly what the ACLU would not want him to do, right? They’d say that he should voice his dissent.

Exactly. And what we both realized, and it was somewhat surprising, was that his position and our position were not as far apart as you might think. The town reacted to the threat of Nazis by telling Holocaust survivors to just let it pass. This is the wrong thing to do.

What Ben wanted was to organize a counter-demonstration — if you don’t like the speech, make your own speech to oppose it. For the ACLU to say the Nazis had a right to speak does not mean that we don’t have an obligation to oppose it.

Anti-Nazi activists in Skokie, Illinois, on July 4, 1977 (public domain)

Let me backtrack. Ben Stern said to you “we won’t agree, but we’ll be friends.” It is my observation, and I don’t think I am alone here, that there are some corners of the Left today that would never say what Ben Stern said.

The Left, whatever that is, has never been particularly friendly for free speech other than for themselves.

I used to joke at the ACLU that when people said the problem with protecting free speech is that so few Americans believe in it, I would say no, you are wrong, everyone believes in free speech so long as it is their free speech. And it’s true for everyone. When the speech is something that you hate, it starts to fall by the wayside.

Everyone believes in free speech so long as it is their free speech

Not just for political speech. People who were against smoking, suddenly they were against advertising for smoking. Some people justifiably angry against sexual violence against women were also against the publication of Playboy Magazine.

True believers are often not very tolerant of their opponents. I used to say that speech restrictions are like poison gas. It seems like a wonderful idea when you’ve got the gas, and you’ve got the person you hate in your sights, but one shift of the wind and it’s back on you. This is why we take a case like Skokie.

Ira Glasser, left, grasps the hand of Holocaust survivor Ben Stern in this still from ‘Mighty Ira.’ (Courtesy)

I remember speaking to a group of Black students once, and they were supporting hate speech codes which would ban racist speech. And I tried to tell them it was a stupid strategy. If codes like this were in place in the 1960s, the most frequent target would have been Malcolm X. The people who applied the codes were people who feared him, and he said some hateful things: “blue-eyed devils” and the like.

The problem is always the question of “who gets to apply these restrictions?” The answer is that it’s never the Blacks, and it’s never the Jews, and it’s never the Left.

Most defenders of civil liberties were political liberals, but not all liberals were civil liberties defenders. Either way it is a shame, because civil liberties should have a broad political spectrum.

In this April 24, 1980, file photo, Olympic bronze medalist Anita DeFrantz, right, and Ira Glasser, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, announce a lawsuit in New York by athletes against the US Olympic Committee for depriving Americans the opportunity to compete in the Moscow Games. (AP Photo/Burnett, File)

Clearly you are someone who doesn’t back down from a fight. Does this extend to your personal life? Like, if you are at a supermarket and see someone with 15 items in the 10-items-or-less aisle, do you get in there?

I do not leap into every fray that I come across. It does not dominate my private life. When you spend when as many hours a week, as I did, for so many decades, you learn to pick your spots. We didn’t take every possible case, by the way. We took the ones that would make the most impact on advancing values in the Bill of Rights.

In my personal life, my kids were not aware of what I did. I did not proselytize to them, I did not take them to demonstrations. I didn’t even go to demonstrations myself. I defended the rights of others to go to demonstrations.

Nobody knew how I voted. I never wore a pin. I never made an endorsement. I’ve had friends that have run but I never made a public statement or contribution. If I gave funds, I did so privately. So, no, I never fought for justice in a supermarket.

Former ACLU head Ira Glasser. (Courtesy)

I know you are retired and don’t represent the ACLU anymore, but I am curious how you feel about comments the group has made since Charlottesville, where they appear to have expressed regret for defending that march. It leads me to believe that the ACLU would not take the Skokie case today. Is this something you’d rather not get into?

Yes, on some level it’s something I don’t want to get into… but I won’t duck the question.

There’s a good chance that it’s true, that they wouldn’t take the case now. When the ACLU of Virginia took the Charlottesville case, the national ACLU backed off. They didn’t support them. They said we will not support the free speech rights of people who are carrying guns.

Now, there was no evidence those guns were loaded, no evidence they were ever fired. The ACLU never objected to the Black Panther Party marching around in the 1960s with guns. Never a single time opposing that. Now, it’s one thing to oppose violence. Shooting someone might be a form of expression, but it’s not the kind of expression the First Amendment protects!

The one person killed in Charlottesville was killed with a car. You are going to ban cars?

The problem in Charlottesville is the police screwed it up. They did a terrible job of separating the opposing camps to assure they had the right to express themselves. That’s what the role of police in a demonstration is. The ACLU of Virginia was exactly right in what they wanted to do, the national office backed them off, then later issued a set of guidelines that indicated that before they decided to defend somebody, they would take into consideration what it was they were saying.

That is unprecedented in the ACLU’s history. Completely.

So if Skokie came up today, they might not take it. And it bothers me a lot, not just because I was there for 34 years, but because I feel the ACLU is a unique organization in this country. If you don’t have a strong ACLU defending the right to free speech, regardless of what that speech is, then you lose something that took 100 years to build.

Having one more liberal-progressive organization out there is nice if you are a liberal or a progressive. But there are a lot of liberal-progressive organizations out there. There’s only one ACLU.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 2nd, 2020

October 2nd, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: