ExxonMobil’s production numbers in the Permian basin in West Texas and New Mexico appear to have deteriorated in 2019, according to new analysis, calling into question the company’s claims that it is an industry leader and that its operations are steadily becoming more efficient over time.

Chastened by years of poor returns and rising angst among its own shareholders, ExxonMobil narrowed its priorities in 2020 to just a few overarching areas of interest, focusing on its massive offshore oil discoveries in Guyana and its Permian basin assets, two areas positioned as the very core of the company’s growth strategy.

Exxon has long described its Permian holdings as “world class,” and the company prides itself on being an industry leader in both size and profitability.

“For our largest resource, which is in the Delaware Basin, we’re only just about to unleash the hounds,” Neil Chapman, the head of Exxon’s oil and gas division, said at its March 2020 Investor Day conference. The Delaware basin is a subset of the Permian basin, stretching across West Texas and southeastern New Mexico.

But while the pandemic and the oil market downturn forced cuts in spending, the company’s belief in the Permian and its assurances about its quality remain unshaken.

This is despite ExxonMobil’s wells in the Permian producing less oil on average in 2019 than they did in 2018, according to a new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). The decline raises “troubling questions about the quality” of those assets, the report states, and the company’s “ability to sustain the industry-leading production that the company has been touting to investors.”

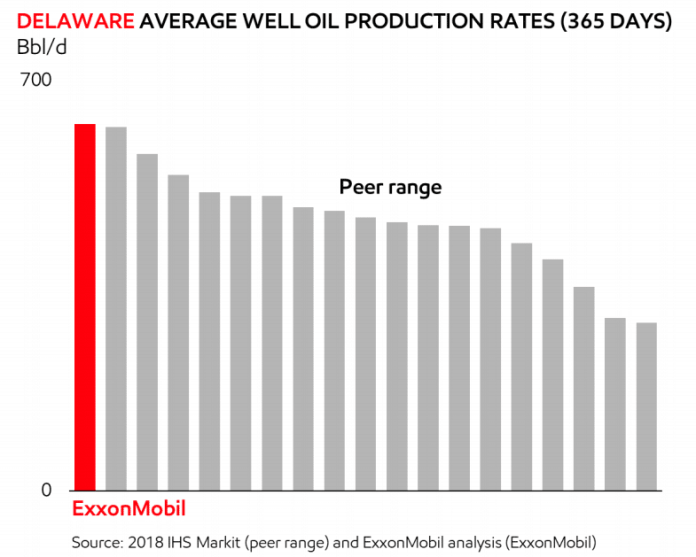

IEEFA used data from IHS Markit, an industry analysis firm, the same data that Exxon itself uses in its presentation to investors. The data show that Exxon’s average first-year production per well in the Delaware portion of the Permian basin fell from 635 barrels per day in 2018 to 521 barrels per day in 2019. The slip in performance came as the company drilled twice as many wells over that timeframe.

“[A]s ExxonMobil drilled more Delaware Basin wells, the performance of its wells deteriorated year-over-year, both absolutely and in comparison with peers,” IEEFA analysts Clark Williams-Derry and Tom Sanzillo wrote in their report. Data for 2020 is not complete, but so far, the numbers suggest a further deterioration.

Over in the Midland basin, an oil-rich area in West Texas, Exxon was much more active, drilling over 630 wells between 2016 and 2020, the third most of any company in the region over that period. But its performance was even worse compared to its peers, with the oil major ranking eighth in per-well production out of the top 20.

ExxonMobil’s rankings in per-well production in the Delaware and Midland basins take another dip once the length of the well is taken into account. Over the past decade, the industry has steadily increased the horizontal length of each well, as longer wells tend to produce more oil. When the IEEFA analysts adjusted Exxon’s numbers to look at production per 1,000 feet of length – a common industry metric to compare apples to apples – Exxon’s ranking in the Midland basin fell from eighth to 12th.

The “middling” performance, as IEEFA described it, stands in stark contrast to rhetoric from the company about how it sits at the very top of the industry and continues to strengthen its position and achieve efficiencies.

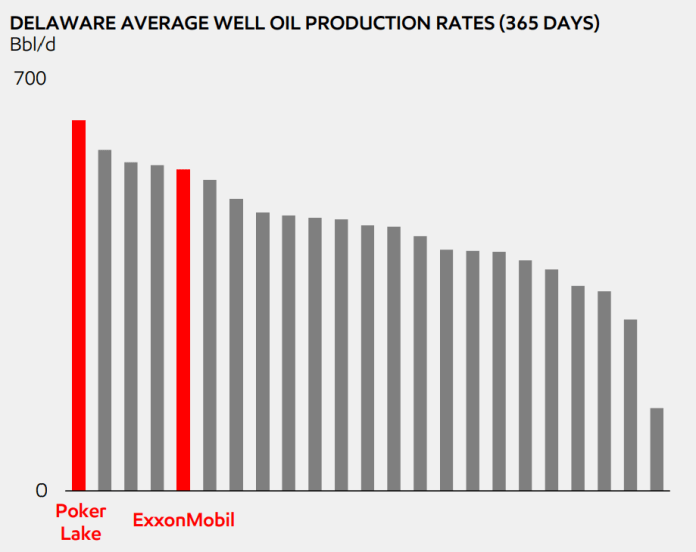

In their annual investor presentation in 2020, the company said it had the best per-well performance out of all companies operating in the Delaware basin. In 2021, they single-out their “industry-leading performance at Poker Lake,” a large drilling project in New Mexico.

But the same chart shows their ranking in per-well production fall behind other companies, a quiet admission that suggested something was amiss. Still, an accompanying chart claims average production improving in each year between 2018 and 2020.

“They say ‘we’re getting better every year.’ And yet their first-year production is falling. It makes no sense,” Clark Williams-Derry told DeSmog. “Something doesn’t add up.”

The spin around the company’s Permian production is not isolated to PowerPoint slides. Constant and steady improvement is how the company consistently frames its operations in the Permian.

“What we’re seeing in the Permian … is the progress at the improvements that that business is making,” ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods told investors and analysts on an earnings call in March 2021. He added that the company’s performance was “impressive” and that “we would see significant improvements with time.” Three months earlier, Woods told investors that the “value proposition continues to grow” for its Permian basin assets.

Williams-Derry said that the middling drilling performance would not raise as much alarm if the company was leading the industry on costs and profitability – as Exxon routinely claims to be. If the company was producing a modest amount of oil, but making a ton of money on it, investors would likely be pleased.

But Exxon has produced a decade of poor returns for its U.S. upstream unit, which has lost a combined $10.5 billion since 2014, dragging down company-wide earnings. The Permian is considered its crown jewel out of its U.S. holdings.

“If Exxon is blowing smoke, there must be fire somewhere. They are kind of blowing smoke about this. It raises questions – is there a fire? We don’t know,” Williams-Derry said. The company does not delineate earnings by particular projects that would allow for a clear look at how its Permian wells perform financially. Instead, it provides headline earnings numbers for the whole enterprise.

In February, DeSmog reported that a former ExxonMobil employee-turned-whistleblower filed a complaint with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), alleging that Exxon was overvaluing its assets by roughly $41 billion at the end of 2020. And in January, the Wall Street Journal reported that a separate whistleblower filed a complaint last year, alleging that Exxon was overvaluing its Permian assets specifically.

ExxonMobil did not respond to a request for comment.

The production missteps and the seeming obfuscation, said Williams-Derry, “calls for greater transparency and greater scrutiny from a more active and more engaged board that’s not just a rubber stamp for the management that has been actively failing its investors for more than a decade.”

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 13th, 2021

June 13th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: