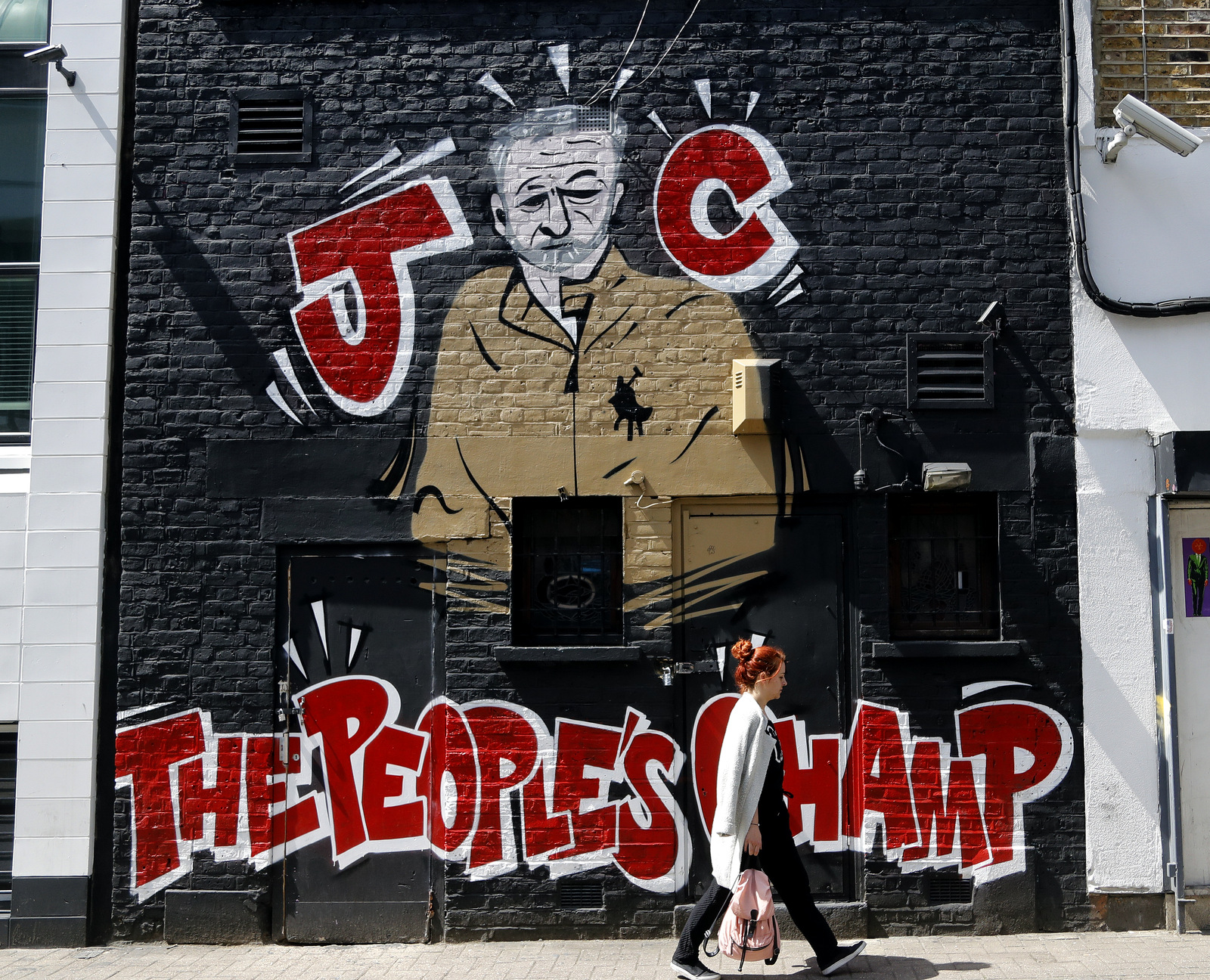

A woman walks past a Jeremy Corbyn mural in Camden, London on, June 1, 2017. (AP/Frank Augstein)

Last week’s elections in the United Kingdom were a fiasco for Prime Minister Theresa May, whose Conservative Party lost 12 seats in Parliament, weakening the government just ahead of crucial negotiations on the U.K.’s exit from the European Union. The elections had been called by May with the hope of an opposite outcome; the goal was to take advantage of the Tories’ strong lead in the polls to strengthen the Conservative majority and increase May’s power.

One factor in this evaluation was the hope that voters would see Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn as a radical leftist, and in particular as a weak leader compared to the current Prime Minister. Yet Corbyn is the one who succeeded in exploiting the political situation in recent weeks, leading to a gain of 32 seats for Labour, and forcing May into a precarious situation where she must rely on votes from small Northern Ireland parties to obtain a majority in Parliament.

Theresa May came to power thanks to the Brexit vote held one year ago, when the people of the U.K. voted to leave the European Union (E.U.), leading to the resignation of then-Prime Minister David Cameron. The referendum had originally been called by Cameron as a way to beat back growing internal pressure from the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), led by Nigel Farage.

The political élites lost that battle, as the British population sent a strong message not only to the E.U. institutions in Brussels and Frankfurt, but principally to its own political representatives, who were seen as pursuing their own interests while ignoring those of large segments of the population.

Immigration was a major issue in the Brexit vote, leading many commentators to brand Leave voters as racists, as has happened with anti-establishment (or populist) movements across the Western world; the same line was used in the U.S. elections, in an attempt to downplay any legitimate reasons to vote for an outsider candidate.

There is no doubt that racism is present with regard to immigration, but academic research has shown that economic difficulties exacerbate racial attitudes, even changing people’s visual perception of others. [See A. Krosch, and D. Amodio, Economic scarcity alters perceptions of race. PNAS, May 6, 2014.]

This aspect can feed into a larger mix that leads voters to support candidates who are critical of the current political institutions. Another widely circulated study in Europe has shown that economic crises lead to the rise of more extreme political parties. [See M. Funke, M. Schularick, C. Trebesch, The political aftermath of financial crises: Going to extremes, VoxEU.org, November 21, 2015]

Through an analysis of 20 advanced democracies from 1870 to date, the authors found that in addition to the obvious case of the 1930s, which saw the advent of Nazism and Fascism, another period of heightened support for far-right parties was precisely that after the crisis that began in 2008.

A Weak Recovery

The recovery since that time has been weak, and particularly unequal among socio-economic classes, so it is not surprising that the underlying economic difficulties have fueled protest votes whenever the population is given the possibility to stick it to the politicians. The June 8 general election in the U.K. shows just how important it is to recognize these undercurrents, as opposed to seeking support on collateral issues that many voters may ultimately recognize as superficial.

Given the victory of Leave in the Brexit vote last year, Theresa May sought to capitalize. Facing resistance in the Parliament, the Prime Minister thought that an election campaign focused on strong leadership to lead the U.K. out of the E.U. would naturally find a great deal of support.

What May ignored, however, is the need to link the political argument to people’s basic economic needs. She paid lip service to the issue, promising benefits for the British people by leaving the European common market, and announcing new initiatives to expand trade. The voters didn’t buy it though, because at the same time, May found herself on the wrong side of the all-important issue of austerity, leaving a massive flank open to Corbyn and Labour.

May took two significant hits on economic issues during the short campaign. First of all, she came under fire for cuts to the police budget, in the aftermath of recent terror attacks. May was Home Secretary – responsible for national security, policing, immigration and citizenship – from May 2010 to July 2016, during which time total police numbers in England and Wales fell by almost 20 percent. May’s response to the accusation of having weakened public safety capacity to stop terror attacks was to brand Corbyn as unprepared for office, and claim that he would be even worse. Sound familiar to American voters?

The English Defence League marches in Newcastle calling for the repatriation of immigrants in the wake of the EU referendum vote.

May also boasted about giving police increased powers to deal with terrorists. The image that stuck, however, was that of having cut the budget in a key area when resources are needed to guarantee security.

The second instance in which May was pummeled was the so-called “dementia tax.” The Conservatives presented their social manifesto in April, with a plan to change the rules about how the elderly pay for home care. Corbyn immediately branded the scheme a “tax on dementia,” as people who need long-term care at home would be forced to use more of their assets to pay for it: the state would be allowed to draw on a pensioner’s home equity to pay the bill.

May’s stumble on this point played into the larger narrative of the negative effects of the Conservatives’ austerity policies in recent years. In fact the backlash regarding social spending cuts had already become manifest at the time of the Brexit vote. The week the Brits went to the polls a year ago, newspapers ran headlines on poverty increasing for the first time in a decade, clearly linked to the social welfare cuts presented as “necessary” to deal with the economic crisis.

Fed Up with Austerity

Elsewhere in Europe, the U.K. has been presented as a success story, a country that has made the “tough choices” necessary to fix the budget and allow for growth again. It’s a common refrain, based on the monetarist ideology, which holds that austerity is the magic formula that will create confidence and thus kick-start economic activity.

A protester carries a sign during a rally prior to the opening of the new European Central Bank (ECB) headquarter in Frankfurt, Germany, March 18, 2015. (AP/dpa, Arne Dedert)

The reality is usually the opposite. Cuts to social services and investment hurt the population’s standard of living, and inhibit growth; papering over this by pointing to the rebound after the fall has become a favorite pastime of neoliberal economists and politicians.

What we have seen throughout the Western world in the past year is that the population is no longer buying it. The hollowing out of the middle class in the name of promoting economic and financial globalization has led to a revolt of voters against the Establishment.

Theresa May, who became Prime Minister thanks to last year’s first manifestation of this protest vote, approving the U.K.’s departure from the E.U., now risks becoming a victim of that same revolt.

May attempted to exploit nationalist support for Britain to strengthen her majority in Parliament, but she did so by focusing on issues that proved to be weaker than expected when not tied to the underlying discontent in the population, fueled by the reduction of living standards and the increase in economic insecurity.

Jeremy Corbyn, who campaigned unabashedly on a leftist, anti-austerity program, was able to intersect part of the same anti-establishment sentiment that fueled the Brexit vote, and turn it to his advantage. The results of the elections in the U.K. demonstrate once again that the “populist” revolt is not a one-way street.

The Conservatives are still the leading party in Parliament, but it is now clear that they need to review their own policies from recent years, and recognize that the protest vote will turn against whoever defends a status quo that is not working for a large part of the population.

Andrew Spannaus is a freelance journalist and strategic analyst based in Milan, Italy. He is the founder of Transatlantico.info, that provides news, analysis and consulting to Italian institutions and businesses. His book on the U.S. elections Perchè vince Trump (Why Trump is Winning) was published in June 2016. He writes for Consortium News where this editorial first appeared.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Mint Press News editorial policy.

Source Article from http://www.mintpressnews.com/europe-struggle-wave-populism/228933/

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 16th, 2017

June 16th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: