The story of the ruthless promotion of OxyContin by Purdue, the pharma company owned by the Sackler dynasty, is a shocking page-turner, says Melanie Reid

Melanie Reid Wednesday May 12 2021, The Times

In 1996, at a luxury country club in Phoenix, Arizona, an army of drug reps gathered for the launch of an exciting new product. OxyContin, Richard Sackler promised them, was a revolutionary treatment for pain and would lead to “a blizzard of prescriptions which would bury the competition”.

The painkiller, an opioid with a patented slow-release coating, was designed for a vast market — the one in three Americans suffering chronic discomfort in their backs or necks, or from arthritis or fibromyalgia. Reps were to push it as a twice-a-day pain-relief miracle, marketed as “to start with and stay with”. A friend for life.

Sackler, the senior vice-president of Purdue, the family company, and his executives knew that the product was twice as strong as morphine, that no proper studies had been done to check its addictive qualities, and that some patients didn’t get 12-hour relief and needed a top-up. However, their drug had been approved.

Funnily enough, in one of the gasp-out-loud moments that Empire of Pain is loaded with, just a year later the official from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) who authorised OxyContin joined Purdue on a salary of $400,000.

About 700 voracious sales reps fanned out across the US, carpet-bombing nearly 100,000 physicians. Under Sackler’s direction they were to claim that fewer than 1 per cent of patients became addicted, referring doctors to literature produced by physicians paid or funded by Purdue. Because Purdue also owned a market research firm, the reps knew who to target — doctors prescribing lots of painkillers in areas where manual labourers had compensation for work injuries and disabilities. The reps called these doctors “whales”, the name given by casino operators to high spenders.

Twenty-five years on we know that this tale ends with millions of Americans addicted to opioids. Within a year of launch — in the eastern rustbelt states, the Appalachians and Ohio — OxyContin was being ground up, snorted and injected. Within five years, Patrick Radden Keefe writes, “communities began to resemble a zombie movie” as one previously well-adjusted functioning adult after another went into a spiral of addiction.

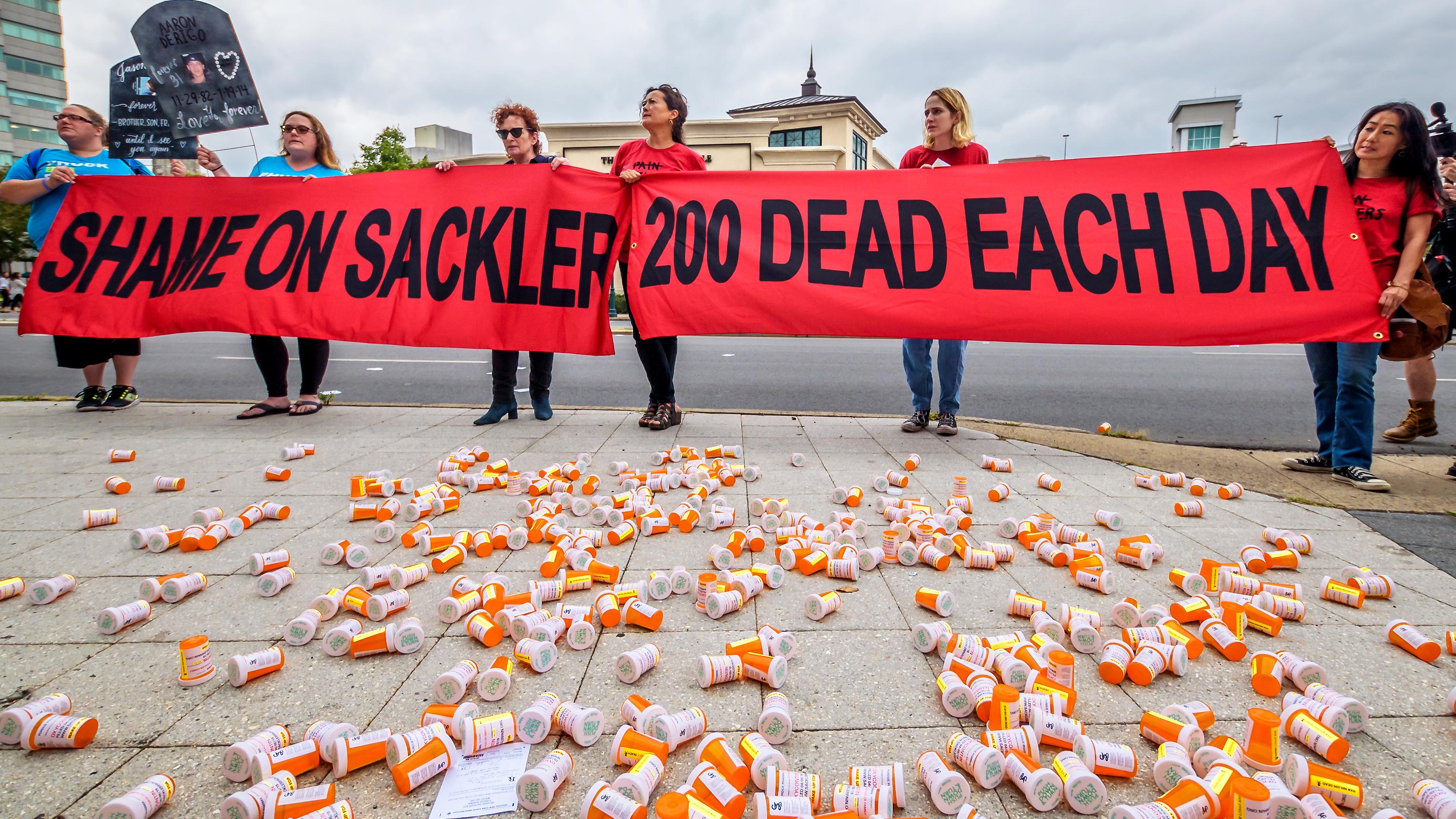

Then, as supply was tightened, heroin dealers moved in, and fentanyl followed. OxyContin wasn’t the only prescription drug to blame, but the facts speak for themselves: since 1999 about 500,000 Americans have died from opioid-related overdoses, a continuing health crisis sometimes described as the crime of the century.

Pill Man, a skeleton made from artist Frank Huntley’s prescription bottlesBRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/GETTY IMAGES

Empire of Pain reads like a real-life thriller, a page-turner, a deeply shocking dissection of avarice and calculated callousness. Informed by recently released court documents, internal emails and memos, plus 200 interviews with those close to the family, Radden Keefe’s epic investigation lifts the veil of secrecy over the billionaire Sackler clan. We knew some of this story; it turns out we didn’t know the half of it.

The first section of the book brings alive the dynasty from its beginning — three bright Jewish brothers, sons of European immigrants, who left Brooklyn to become doctors, admen, hustlers, businessmen and philanthropic giants. Arthur Sackler, the eldest brother, man of many wives, made the family’s first fortune marketing Librium and Valium for Roche in the 1960s, setting the template for cultivating officialdom and politicians, buying up experts on big salaries and ruthlessly targeting sales, no matter the consequences. (British readers will find themselves giving thanks for a public health system — however flawed — that protects against such egregious capitalism.)

Valium was the first $100 million drug in history — largely because Arthur Sackler marketed it to solve the problem of “being female” — and 30 years later OxyContin hit similar paydirt. With naked cynicism Richard Sackler, Arthur’s nephew, priced the painkiller so that increased dose strength meant greater profits. Despite worrying feedback about addiction, sales reps were incentivised to encourage doctors to “titrate” up — increase the dose. Purdue offered patients a free 30-day course; within five years it had subsidised 34,000 such prescriptions. Within four years sales had hit $1 billion, surpassing those of Viagra. The company paid reps an average bonus of $250,000 and doubled its salesforce. Factories struggled to meet demand.

Many people who were prescribed OxyContin found themselves experiencing withdrawal symptoms between doses. By 2001 the company knew that 20 per cent of all OxyContin prescriptions were being written on a more frequent dosing schedule than the recommended 12 hours and that the drug was widely abused. Richard Sackler’s response was bullish. Such concerns must be, to use his words, “obliterated”. He taught his salesforce to describe addiction as a psychological malady. What Purdue should do was “hammer on the abusers in every way possible”. These hillbilly junkies were “the culprits”, he declared. “They are reckless criminals.” Arthur Sackler had adopted exactly this approach when women became addicted to Librium and Valium — the addicts were to blame.

In under 20 years OxyContin generated $35 billion. Even after Purdue pleaded guilty to charges of misbranding in 2007 and was fined $600 million, the family kept selling it. At this point you find yourself shouting: “Why didn’t the authorities stop them?” The answer: aggressive Purdue lawyers (including Rudy Giuliani) and political strings pulled. The company’s legal top dog set the rule: concede nothing. Meanwhile his secretary — addicted to OxyContin, which she had taken for back pain — was snorting crushed pills on her way to work. The company settled every legal case, ensuring all court documents were safely locked away. Secrecy prevailed. An army of PR specialists kept the family name out of negative stories about Purdue.

Between 2008 and 2016 the family paid themselves $4.3 billion in OxyContin profits. Purdue strategised about selling to children as young as 11, and expanded into Latin America and Asia. As late as 2014, with declining sales, family members floated a project to produce drugs to treat addiction. The “abuse and addiction” market would be a good fit, they decided. They were clever at complementary business models: for years Purdue reps had been selling the laxative Senokot as a chaser to OxyContin, because opioids cause constipation. Again, those little killer details.

Richard Sackler had a bulldog called UNCH, after the stock-market abbreviation for “Unchanged”, which indicates that a company’s share price ended the trading day at the same level it started. UNCH would defecate in the office, and its owner had a tendency not to pick it up.

Purdue went bankrupt in 2019, and in the final days of the Trump presidency the family offered to contribute the comparatively tiny sum of $4.3 billion to help to settle thousands of outstanding lawsuits. The only Sackler to spend any time in prison was Madeleine, Richard’s socially minded niece, and that was while she was making a film in a maximum-security jail. In the part of Indiana where she filmed there were 116 opioid prescriptions for every 100 residents; and nearly 80 per cent of prison inmates had a history of substance abuse. (George Clooney was a c0-producer.)

The Sackler dynasty was riven with fall-outs. After Arthur Sackler died in 1987 his heirs sold Purdue to the two remaining brothers, Mortimer and Raymond (father of Richard), before OxyContin was launched. Arthur’s lot later distanced themselves from those they called the “OxySacklers”. But Radden Keefe, a writer for The New Yorker, says that Arthur created the world in which OxyContin could succeed by pioneering medical advertising and marketing, co-opting the FDA, mingling medicine and commerce, and the total denial of any family moral responsibility.

Madeleine, the right-on film-maker and granddaughter of Raymond Sackler, dismissed any link between her and the opioid crisis. For a Sackler, she lived relatively modestly — she paid only $3 million for her house — but she was an OxyContin heiress. Her father was a longtime director of Purdue who presided over the success of the drug. All the heirs of Raymond and Mortimer Sackler benefited from family trusts in which OxyContin money was kept, routed through the tax haven of Bermuda.

Ever since the 1950s the Sacklers — aggressively disassociating themselves from the source of their wealth — had pursued showy, high-end philanthropy, endowing vast sums to galleries, theatres, medical schools, universities, museums and libraries in Harvard, Washington, New York, Oxford, Tel Aviv, Paris — always on the condition that their name was above the door. In London their name was everywhere.

It is the measure of great and fearless investigative writing that it achieves retribution where the law could not; thus Radden Keefe won the Orwell prize for his previous book, Say Nothing, about hidden crimes in Northern Ireland. The greedy, shameless Sacklers have not lost their personal wealth. But Radden Keefe has, word by forensic word, dismantled what mattered most to them: their reputation. Many of the grand buildings have already dropped the tainted name. This book should finish the job. Exhaustively researched — there are 100 pages of source notes — and written with grace and gravity, Empire of Pain unpeels a most terrible American scandal. You feel almost guilty for enjoying it so much.

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe (Picador, 560pp; £20)

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 18th, 2021

May 18th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: