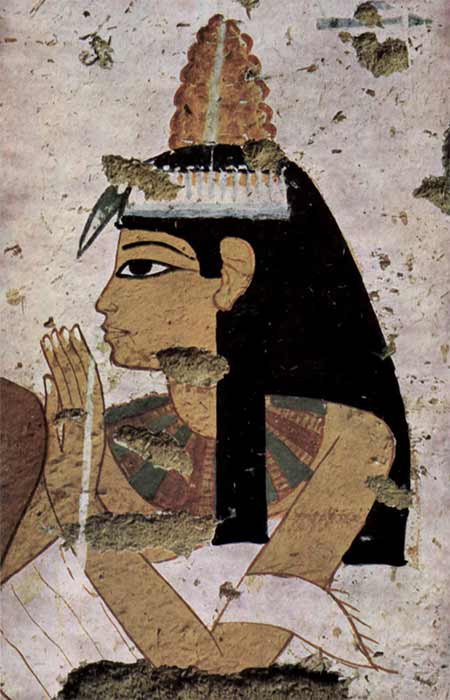

One of ancient Egypt’s most-enduring embalming enigmas has to be its cryptic head cones. These unusual objects can be seen in tomb paintings perched atop the heads of both mummies and living people. They resemble white domes or cones, and are often decorated with lines and dots and covered in a reddish colour, assumed to be liquid incense. They appear infrequently at first, in tomb paintings of Thebes during the early New Kingdom (circa 1550 BC), and become popular during and beyond the reign of Hatshepsut (1473-1458 BC).

The cones are never named in accompanying texts, leaving researchers frustratingly in the dark over their true function and even what they were called. The academic consensus since the late 19th century sees the cones as slow-melting incense diffusers, helping the wearer achieve a state of ritual purity before the gods and the dead. It is believed the cones, with their heady aromas, would have helped blur the line between the living and the dead. A more recent hypothesis by Joan Padgham formulated in 2012 re-imagines the cones as visible expressions of a person’s ba, or soul.

A head cone atop a woman’s head, distinctive in colour and form, and appearing not unlike a beehive. Tomb painting, Thebes,1350-1300 BC. ( Public Domain )

The current author (Perrin) proposes a new theory to address the cone conundrum, arguing that the cones served two primary functions. The first was religious: they were personal symbols of resurrection modelled, in wax, after the benben stone – the original mound of creation and inspiration for the pyramids. Second, the cones were symbols of class status, similar to the ornate wigs, garlands, and jewellery seen in the same tomb paintings.

An Archaeological “Cone of Silence”:

By 2010, archaeologists were still perplexed, a century on, as to the exact nature, function, and even name for the strange cones. Since they had yet to actually discover one in an archaeological context, they existed only in paintings, in their own archaeological “cone of silence”. When they were first studied by western Egyptologists in the 1880s, it was believed they had been real cones made of solid perfumed unguent used to scent and cleanse the hair and body (similar to some African tribes).

One of the Amarna graves found with a head cone. (Image: Courtesy of the Amarna Project via Antiquity Publications Ltd )

Then, in the 1950’s, academic opinion shifted towards viewing the cones in artistic terms, as objects that were not real.

Like this Preview and want to read on? You can! JOIN US THERE ( with easy, instant access ) and see what you’re missing!! All Premium articles are available in full, with immediate access.

For the price of a cup of coffee, you get this and all the other great benefits at Ancient Origins Premium. And – each time you support AO Premium, you support independent thought and writing.

Jonathon Perrin is the author of Moses Restored: The Oldest Religious Secret Never Told and latest book: The Pharaoh Behind the Festivals

Top Image : An Egyptian woman wearing a mysterious wax head cone, which is morphing 2) into the benben stone, atop which sits 3) the bennu bird , symbol of resurrection, all set before 4) the Great Pyramid , the architectural climax of mound expressionism, behind which rises 5) the morning sun, called weben by the Egyptians. This rhymed with benben, and provided an important linkage between the rising of the primeval mound and the solar disc. (Image: Design by Jonathon Perrin)

By: Jonathon Perrin

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 12th, 2022

March 12th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: