They say we just need food to survive, but we all know we eat good food to really live!

The ancients knew this as well, and that sentiment was echoed across time and cultures, creating vibrant, delicious cuisines made from regional foods to sustain, nourish and nurture—foods that were sometimes good enough for the gods!

Dig in to these five mouth-watering and sometimes surprising foods of the ancient world.

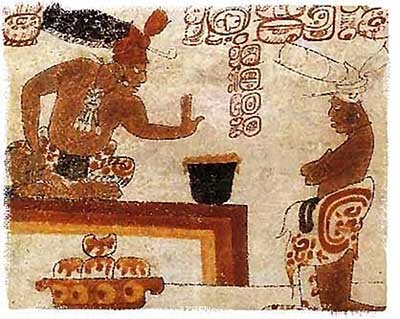

Xocolatl: A Spicy Chocolate Drink from the Maya Gods

Many of the ancient peoples around the world believed food was given to humanity from the gods for their survival. Some of the foodstuffs that they consumed were considered so special, tasty, nutritious, and/or unique that these items were considered “gifts of the gods.” For the ancient Maya people, chocolate, or xocolatl as they called it, fit that extraordinary role.

Archaeologists have traced the cultivation of chocolate back to at least 900 AD in Mesoamerica. But the way it was consumed back then was not as a sweet, melt in your mouth, piece of heaven or a creamy decadent dessert as we enjoy it today; for the ancient Maya, and later Aztecs, chocolate was more of a smooth, bitter, energizing drink. Xocolatl translates to ‘bitter water’ and it also gave us the English word ‘chocolate.’

These days, drink mixes or chocolate bars labeled as “Maya chocolate” or “Aztec chocolate” generally contain cinnamon and sometimes black pepper alongside the chili pepper. Only the latter of these flavorings was used in the preparation of the ancient drink. Back then, a simple xocolatl recipe would often include hot water, ground and roasted cacao nibs, chili, and sometimes roasted maize, honey, vanilla, or a spicy plant known as the ear flower.

Although the Aztecs later transferred xocolatl to an elite treat for the royals and priests, for the Maya, this drink was believed to be a gift for all humans, so it was available to people in every social standing. This was an energizing drink that was consumed daily, much like a morning coffee greets many of us today, but it also served ritual and healing purposes.

A possible Maya lord sits before an individual with a container of frothed chocolate. Public domain

Borscht – A Medieval Peasant Food that Traveled to Space

There are few foods that create as much international debate as the soup known as borscht. The two big contenders for the soup’s homeland are Russia and Ukraine. Although debate continues, food historians think they have solved the mystery.

Most of them agree that the origins of the soup come from sometime between the fifth and ninth centuries AD in the area that is now known as Ukraine. But borscht would have been different back then. For one thing, the main ingredient was cow-parsnips, which were called “b’rshch” in the Old Slavic language.

Medieval herbalists wrote that cow-parsnips were usually collected in May, before the shoots became too tough and stringy. And then a cook would chop up the flowers, stems, and leaves, put them in a pot with water, and leave the mix to ferment. When ready, the sour-tasting liquid, which was also believed to be a miracle cure for hangovers, would be combined with chicken or beef broth, egg yolks, and cream or millet meal, to make a soup.

These days borscht may be considered a wonderful comfort food but given the nature and simple ingredients in its origins, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the tasty tart soup was considered a ‘peasant’ food. The nobility didn’t start to take on the humble fare until well into the 17th century. But that decision meant that borscht was going to see some big transformations. Long gone were the days when cow-parsnips were the key to the food – new sour options such as lemon, fermented flour or rye bread and water (called ‘kissel’ with flour or ‘kvass’ with bread), sorrel, and cabbage had replaced them.

The Ashkenazi Jews are also credited with taking borscht to the United States, where their habit of eating the soup during holidays in the Catskill Mountains led to the region being called the ‘Borscht Belt.’ And in Soviet Russia novelists wrote about borscht, some politicians ate it every day, and the cosmonauts even took freeze-dried borscht into space!

Ukrainian borscht red soup with garlic buns. Source: FomaA / Adobe Stock

Crowdie & Cranachan – From Ancient Curds to a Traditional Scottish Sweet Treat

People have been drinking cow’s milk and using it to make cheese for thousands of years. In Scotland, the history of cheesemaking is traced back to the ancient Picts. It is said that almost every crofter or small farm holder in the Scottish Highlands would make their own cheese, which became known as crowdie.

There used to be two crowdies in Scotland – a porridge and the soft cheese. These days, the term refers to the cheese, which is sometimes coated in oats too. In the early days, cheesemakers made crowdie by letting raw milk sour on a warm windowsill or by the fire. Then they would drain the whey and the end product would be a crumbly white cheese.

Crowdie has often been served with oat cakes in preparation for a get-together in which whisky would be served. It has also been mixed with oatmeal and black peppercorns to make black crowdie, also known as Gruth Dubh .

Cream crowdie – adding oats and honey to crowdie to eat it at breakfast – inspired a dessert called Gruth is Uachdar , more commonly known as cranachan. This is a dieter’s nightmare and a foodie’s dream. It is made with cream, honey, crowdie, oats, raspberries, honey – and let’s not forget the dram of Scotch whisky for a little extra flavor!

Cranachan, traditional Scottish dessert with whipped cream, whisky, honey, strawberries, blueberry and oatmeal. Source: artemidovna / Adobe Stock

Holishkes – Faith Accompanies Hearty, Humble Cabbage Rolls

The humble cabbage roll: a filling, comfort food with a distinctive taste and budget-stretching abilities. Holishkes may be Jewish in origin, but the principle behind them is found across ethnicities – use an abundant or cheap vegetable, save on meat by adding rice, and cook it in something tasty to provide the family with a hearty, healthy meal.

Some Jewish historians believe that holishkes, which are known by many other names across Eastern Europe, were a favored dish of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jews as far back as 1500 years ago. However, their earliest origins are probably the Middle East as legends say stuffed grape leaves, for example, were first eaten by Alexander the Great’s soldiers when meat supplies were low. The notion later spread and was transformed to suit the palates of Eastern Europe as trade routes developed and people migrated.

These days, we can find the stuffed cabbage leaves with numerous names and various ingredients. Bulgarians, for example, call them sarmi and make them with veal, pork, finely chopped mint, sweet paprika and yogurt. Romanians prefer the meat to be pork and add dill inside and bacon on top. Ukrainians garnish their cabbage rolls with sauerkraut and serve them with perogies, while Russians call them “little pigeons” and add a dollop of sour cream.

But the Jewish version of stuffed cabbage has a mild sweet-and-sour flavor thanks to the tomatoes, vinegar, and sugar – which suits most modern palates over the more traditional option of diced apples or apricots, or a generous sprinkling of raisins inside the rice and meat mix (any of which could be used as a substitute for the sweetness of sugar or to change up the flavors).

Cabbage rolls in tomato gravy. Source: Людмила Лебедева / Adobe Stock

Khachapuri: Traditional, Addictive, Cheese-Stuffed Bread from Georgia

Khachapuri (pronounced “Hatch-ah-POO-ree”) is Georgia’s most famous national dish. There are several regional variations and adaptations and the food is inscribed on the list of the intangible cultural heritage of Georgia. Locals have been hooked on it for centuries.

The word khachapuri is a combination of the Georgian words “khacho,” meaning ‘curd’ and “puri,” which is bread. This name for the food applies to all the versions found in the country. The variety of khachapuri in this recipe hails from the Black Sea region of Adjaria and is also known as lodachka, meaning “little boat” in Russian. It is said to reflect the region’s geography and culture. The people living in the area were renowned for their boat building skill and the egg supposedly represents the sun, which swims in a sea of cheese.

Georgians typically make this savory pastry with a mixture of imeruli and sulguni cheese, but a mixture of farmer’s cheese (or fresh cheese), low moisture mozzarella, and strong, tart feta will get you close to the traditional version.

Local legends say khachapuri should only be made by happy people – if you’re not in a good mood, the flavor of your kitchen creation allegedly changes…and people will think there’s something “off” about it. One way to get happy quick? Think of the delicious khachapuri you will eat!

Khachapuri adjara traditional Georgian cuisine meal. Baked bread with cheese and egg filling. Source: igor_kell / Adobe Stock

Top image: Medieval ancient kitchen table with typical food in royal castle. By Nejron Photo / Adobe Stock

By Alicia McDermott

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 28th, 2021

February 28th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: