The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the division of the National Institutes of Health run by Anthony Fauci, funded a recent experiment in Tunisia in which lab technicians placed sedated beagles’ heads in mesh cages and allowed starved sand flies to feast on them alive. Then they repeated the test outdoors, with the beagles placed in cages in the desert overnight for nine consecutive nights, in an area of Tunisia where sand flies were abundant and ZVL, the disease caused by the parasite that the sandflies carry, was “endemic.”

The experiment was just one of countless tests done on animals with the funding of the NIH, and of NIAID in particular, over the course of decades. Estimates of the number of animals experimented on each year in the United States range from the tens of millions to over 100 million, most of them paid for with taxpayer money. The White Coat Waste Project, a non-profit that advocates against federal animal testing, says that more than 1,100 dogs are experimented on in federal labs annually.

For the amount of money and the amount of suffering entailed, little is produced. Much of it is pointless, to begin with, but even the experiments that purport to measure the safety and efficacy of drugs are all but useless. In NIH’s own words:

Approximately 30 percent of promising medications have failed in human clinical trials because they are found to be toxic despite promising preclinical studies in animal models. About 60 percent of candidate drugs fail due to lack of efficacy.

That’s a 90 percent failure rate.

Most of that failure is due to the fundamental differences between human physiology and the physiologies of mice, or rabbits, or dogs. But even between animals with much closer physiologies, the predictive power of animal tests is unimpressive. Between mice and rats, there’s only a sixty percent chance you’ll get the same result. And when you repeat experiments on the same species, only 4 out of 5 times is the result the same — and closer to 2 out of 3 times with toxic substances.

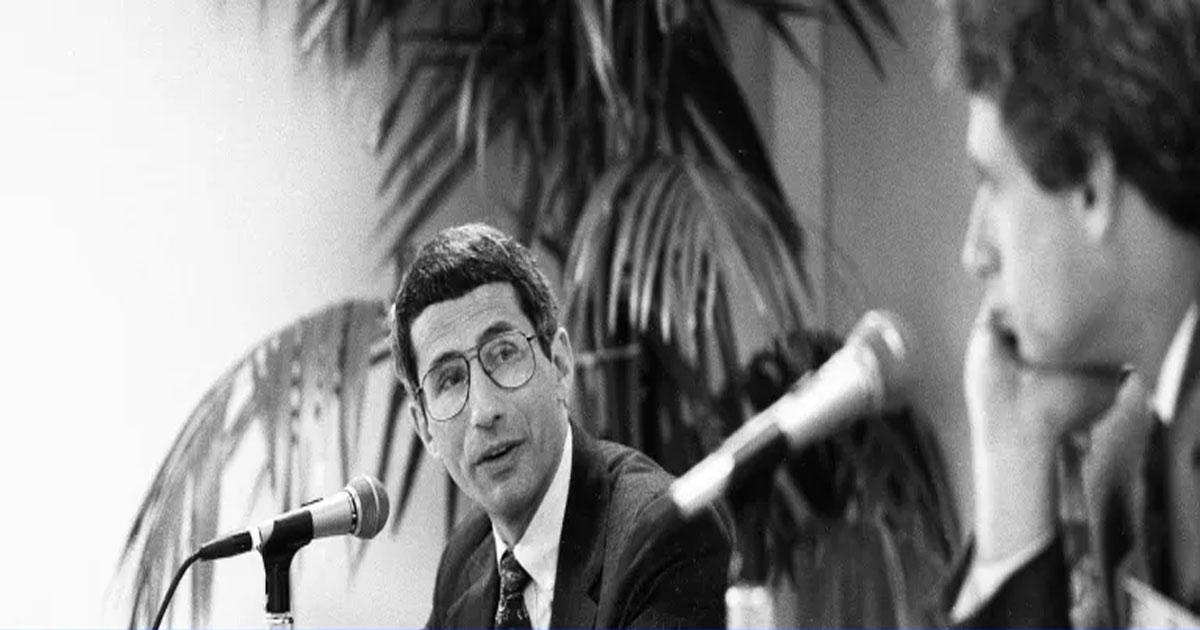

And yet the tests continue unabated, for three reasons: institutional inertia, NIH Director Francis Collins, and Anthony Fauci.

The Tunisia experiment at least had some practical scientific value. Around a half million people a year get ZVL, many of them children, and they generally get it from dogs. The experiment showed that dogs that are infected by the parasite are more attractive to the sandflies who carry the virus than uninfected dogs.

The same can’t be said for other experiments paid for by Fauci’s NIAID. Last year, the institute paid the University of Georgia $424,455 to infect beagles with a parasite before killing them and cutting them open. The purpose of the experiment was to test a drug that, by the investigators’ own admission, had already been “extensively tested and confirmed” in numerous other animal species.

In 2019, NIAID paid $1.68 million to inject and force-feed toxic drugs to 44 beagle puppies, before killing and cutting them open. NIAID paid for the dogs to undergo “cordectomy,” also known as “de-barking,” which is when the dogs’ vocal cords are severed so that lab technicians don’t have to hear them cry and howl in distress. The purpose of the experiment was to generate data on the drug “to support application to the Food and Drug Administration,” even though the FDA expressly “does not mandate that human drugs be studied in dogs.”

Here are some other NIH experiments:

- Beagles were infected with pneumonia in order to induce septic shock and “experimental massive acute hemorrhage,” then given blood transfusions. “After 96 hours, animals still alive were considered survivors and were euthanized.”

- Beagles were infected with anthrax in order to test a vaccine that was already FDA approved.

- “Mongrel dogs” were subjected to induced heart attacks, scanned by MRI, then killed and dissected.

- Pigs, rabbits, guinea pigs, and monkeys were subjected to agonizing pain without anesthesia. These included infecting pigs with a virus that causes “acute respiratory stress, hemorrhagic manifestations, paralysis” and other symptoms; injecting rabbits with bacteria that create severe skin infections and ear lesions and usually death within twelve hours; infecting guinea pigs with a virus that causes “multi-organ failure” and death, as well as “hind limb paralysis or prolapsed rectum”; and infecting monkeys with Ebola and tuberculosis, the latter of which produces symptoms including “rapid breathing, weight loss,” and “inability to drink.”

- Monkeys had parts of their brains destroyed with acid in order to increase their capacity for terror and were then tormented with simulated spiders, snakes, and other things they instinctively fear. These experiments have been ongoing for more than four decades.

The NIH spends more than $40 billion a year on medical experiments. They’re the principal source of funding for basic scientific research in America. The institutes estimate that 47 percent of their grants involve animal testing.

It’s likely that the percentage is much higher for NIAID alone. NIAID commands a budget of $6 billion. There’s an unwritten rule that in order to win an NIAID grant, you have to test on animals.

“Almost all investigators are trained using animal research,” Jim Keen, a former USDA veterinarian, and infectious disease specialist told me. “If you don’t use that model you don’t get funding.”

When a researcher submits an application for NIH funding, their proposal is reviewed, in the first round, by their peers, almost all of whom are animal testers. “It’s sort of incestuous,” Keen said.

According to Garet Lahvis, a former neuroscientist who used to experiment on mice and who has reviewed NIH grant applications, this professional insularity creates a culture of groupthink. “You have institutional inertia because of all these animal experimenters,” he told me. It’s simply taken for granted that a good research design entails animal experimentation since everyone judging it has been trained that way.

Keen, who was the whistleblower in a major New York Times exposé of animal abuse at the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center in Nebraska, believes another reason for the animal-centric culture at NIH is its leadership — namely, Fauci and Collins. “People like Fauci and Collins really believe in that animal model,” he said. “It’s a huge impact having those two at the helm.” The two directors’ unquestioning commitment to animal testing sets the tone for science as a whole: thanks to them, it’s industry standard. “Careers are based on it,” said Keen.

Certainly, Fauci’s career is based on it. Fauci has been testing on animals for close to four decades and failing to produce results for just as long. In the 1980s, the infected chimps with HIV in his quest for a vaccine that still doesn’t exist. When that approach failed, he proposed moving on to other animals. As recently as 2016, he was still touting the likelihood of a new HIV vaccine based on animal studies. After a drug taken for intestinal illnesses showed promise in suppressing HIV in monkeys, Fauci personally flew to Boston to deliver the good news to the drug maker’s executives. Two years later, it turned out to be another dud.

The Fauci of the 1980s at least had an excuse. Animal models may have been disastrous in terms of their predictive powers for humans, but it was arguably the best option scientists had at the time. In 2021, that isn’t even remotely true.

“Knowledge in the life sciences doubles every seven years,” Dr. Thomas Hartung, a toxicologist who directs Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing, told me. “We have about 1,000 times more knowledge now than at the time we designed animal tests.”

Today, scientists can create “mini-brains” to investigate whether and how SARS-CoV-2 affects brain cells. Machine learning software can outperform animal tests in predicting the toxicity of tens of thousands of chemicals in humans. “Organs-on-a-chip” technology uses tissue derived from stem cells to create simulated organs on a slide the size of a USB stick, which can be combined to create simulations of the entire human body. In the near future, AI will likely be able to extrapolate from these simulations to model an entire patient population. That technology could supplant the entire animal trial stage of the drug development process, with results that actually tell you something.

But calling these “alternatives” to animal testing is, in a sense, misleading, Jeremy Beckham, an animal rights advocate and public health expert told me. That would imply that what they were replacing had some utility in the first place.

“These experiments are pretty much all bunk and don’t need an ‘alternative’ per se because they accomplish nothing,” Beckham told me. “It’s like asking ‘What’s the alternative to astrology?’”

Update: Statement from the University of Georgia about the UGA experiment described in the story:

This particular research is being conducted on a potential vaccine, developed at another institution, that would protect humans against a disease that afflicts approximately 120 million people worldwide. Under federal rules, a vaccine must be tested in two animal species before it can be cleared for human clinical trials.

When NIAID decided to fund this research, the agency determined that the research needed to be conducted on a dog model. According to researchers at the UGA College of Veterinary Medicine, beagles are the standard dog model used in this type of research. Because this disease currently has no cure, unfortunately, the animals that are part of this trial must be euthanized. We do not take lightly the decision to use such animals in some of our research.

Nearly every advancement in medicine, medical devices, and surgical procedures has depended on research involving animal subjects. The university adheres to all of the humane standards of the Animal Welfare Act; the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; policies of the university as well as the University System of Georgia; and other guiding organizations.

Additionally, the university has earned and maintains third-party accreditation from AAALAC International.

Over the decades, UGA research has advanced the development of treatments that improve the lives of people, pets, and other animals. These include treatments for:

•Breast and other cancers.

•Infectious diseases such as rabies, Zika, hepatitis B, influenza, and coronavirus.

•Neurological disorders, such as stroke, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s.

•Chronic diseases such as hypertension and obesity.

Leighton Woodhouse is a freelance journalist and documentary filmmaker. This article was originally published on his blog.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 27th, 2021

October 27th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: