The holiest day of the Jewish year, Yom Kippur, means “Day of Atonement”. Marked by confession, repentance, and forgiveness, it takes place ten days after the Jewish New Year. Its origins remain to this day cloaked in mystery. I believe that Yom Kippur traditions connect all the way back to ancient Egypt and the period of religious heresy under Akhenaten and discuss some here. Let’s look at some more connections.

Ten Days, Five Prayers, One God

The numbers five and ten feature prominently during Yom Kippur . They also featured prominently in the lives of Moses and Akhenaten. For example, there are ten days of repentance between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, during which people ask forgiveness of God and their loved ones. These ten days are referred to as the “Days of Awe”.

Moses gave the Israelites Ten Commandments on which to focus their obedience, five types of offerings, and five pillars to the Tabernacle. During the days of the Jerusalem Temple, the High Priest would wash his hands and feet ten times throughout Yom Kippur, and would change outfits five times. There are five main prayers on Yom Kippur, five prohibitions for the people to follow, and confession ( viddui) is said ten times.

Meanwhile, at Amarna, five and ten were important numbers as well. At the front of the Great Aten Temple, there were two sets of five flagpoles flanking the main entrance, totalling ten poles.

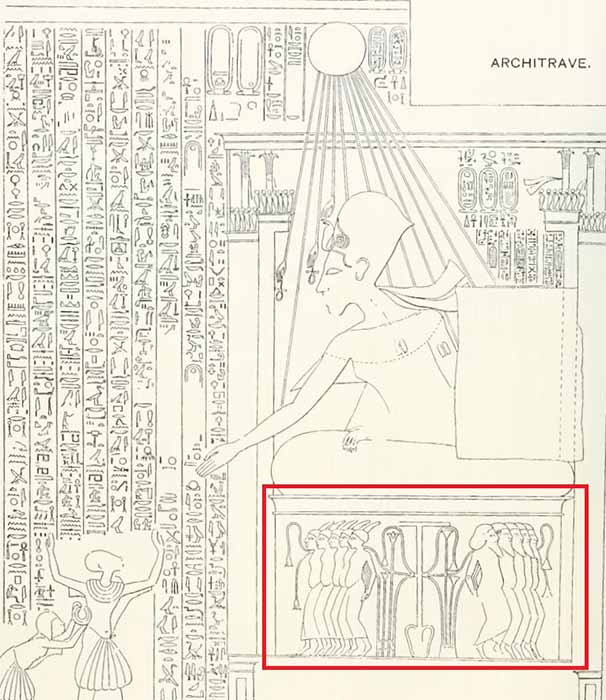

View of the front entrance to the Great Aten Temple in Amarna, seen in a side view; from an inscription in the tomb of Akhenaten’s High Priest Mery-Ra. The king stands in front of the temple blessing offerings to the Aten overhead. (Plate XXVII, from Davies, N. de G., The Rock Tombs of El Amarna: Part I, The Tomb of Meryra. (London, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1908)

In a scene from the tomb of Tutu, his chamberlain, we can see ten foreign prisoners tied up. Five and ten were associated with writing and knowledge (under the god Thoth), likely because writing was associated with five fingers and two hands.

Akhenaten bestows golden necklaces and a promotion upon Tutu, his chief administrator. Underneath the king are ten prisoners bound by the sema tawy, the symbol of Egyptian unity. The entire scene is highly symmetrical, and symbolic of the king’s dominion over all realms. (Plate XIX, from Davies, N. de G., The Rock Tombs of El Amarna: Part IV, Tombs of Parennefer, Tutu, and Aÿ (London, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1908).

We know the priests of Thoth were organized into groups of five, and since Akhenaten respected Thoth, despite his monotheism, he also shared a fondness for the numbers five and ten. Amarna was even built across the Nile from the Temple of Thoth at Khemenu, and was ironically approximately ten kilometers long, north-to-south.

The word soul is mentioned five times in the Torah’s Yom Kippur section. More remarkably, modern Jews share the same ancient Egyptian idea of a person containing five different immortal souls or soul components that would live eternally. The Egyptians envisioned the ka (vital life energy or spirit) , ba (personality), shuet (shadow), ib (heart), and ren (name). Jewish theology meanwhile teaches that each soul passes through five stages during life, and has five elements: nefesh (soul), neshamah (breath of life), ruach (wind), chaya (living one), and yechidah (unique one).

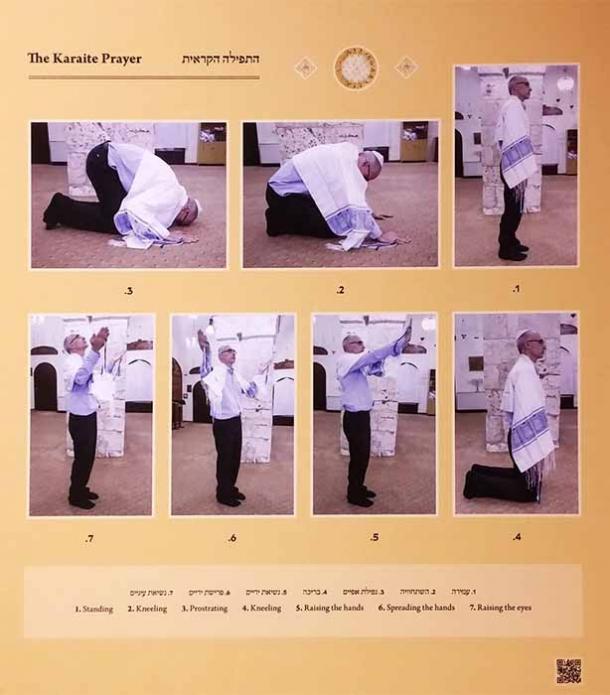

A Karaite Jewish man demonstrating modern prostration in prayer, along with six other prayer positions, including with both hands raised. These curiously echo Akhenaten’s many postures from Amarna. From the Karaite Synagogue and Museum, Jewish Quarter, Jerusalem, Israel. From Tamar Hayardeni. (Tamar Hayardeni תמר הירדני / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Falling on Your Face

Yom Kippur is the only day of the year that Jews will fully prostrate themselves on the ground during prayers. This action is called nefilat apayim, or “falling on one’s face”. Karaite Jews, for example, who regard the Torah as the supreme Jewish Law, still preserve the full practice of prostration.

Meanwhile, the Jewish prayer the Aleinu says: “We bow, and prostrate , and give thanks before the King of Kings of Kings, the Holy One, Blessed is He!” This humbling position is very ancient, and the Torah records many leaders self-effacing themselves by “falling on their faces” before God, including Abraham, Joshua, and even King David.

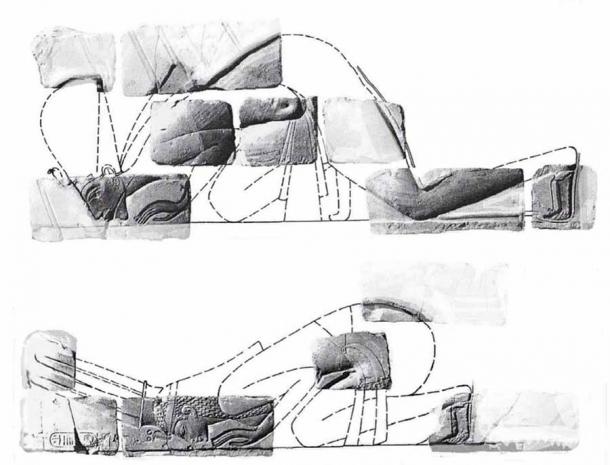

Deuteronomy 9:25 tells us how Moses “lay prostrate before the Lord those forty days and forty nights” . Oddly enough, this is exactly how Akhenaten and Nefertiti worshipped: with hands, knees, and faces all touching the ground. This posture of great humility and sincerity was even adopted by Jesus, who fell on his face in Matthew 26:39: “Going a little farther, he fell with his face to the ground and prayed, “My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not my will, but your will be done.”

Top: Akhenaten prostrates himself before the Aten, in a reconstructed scene from inscribed blocks from Karnak. Bottom: Nefertiti prostrates herself before the Aten, in a reconstructed scene from inscribed blocks from Karnak. (From: Ertman, Earl L., “Images of Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti in the Style of the Previous Reign,” University of Akron, In Causing His Name to Live, Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane, (Brill, Leiden, 2009).

The Lion Sleeps Tonight

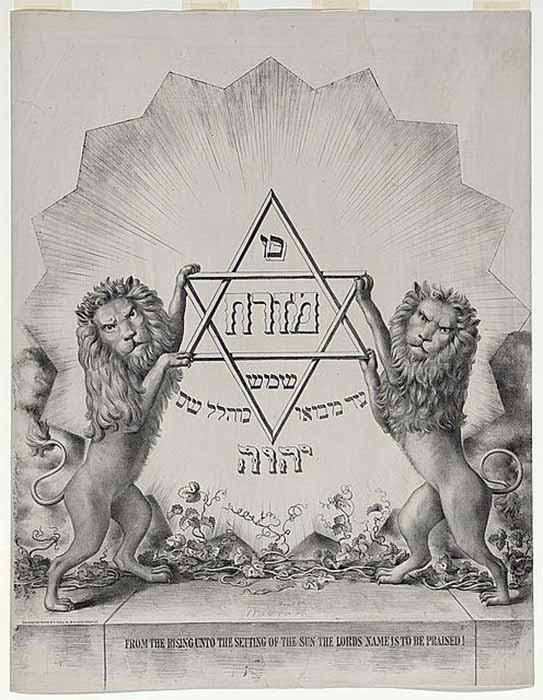

An interesting feature of Yom Kippur is that during prayer services, the Aron Hakodesh that houses the Torah scrolls is left open. This reveals the beautifully embroidered covers made for the precious scrolls, which generally feature the following motifs: the Ten Commandments , the Crown of God, the Tree of Life, the Gateway to the Temple, the Menorah, and two lions.

Lithograph by Henry Schile, 1870-1880, now in the Library of Congress. The quote says: From the Rising unto the Setting Sun the Lord’s Name is to be praised. ( Public Domain )

This last image is symbolic of the Lion of Judah, God’s judgment, and the fear of him. The Hebrew word for lion, aryeh, is an acronym for the High Holy Days. The prophet Isaiah describes a future time of restoration during which the lion and the calf will live together, while Amos likens God to a lion: “The lion has roared, who will not fear? The Sovereign Lord has spoken, who can but prophesy?”

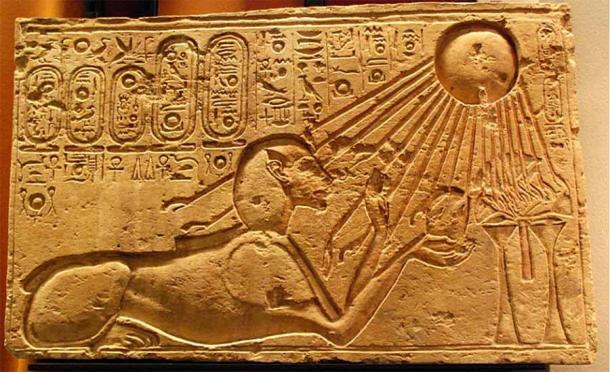

These connections to lions are fascinating because Akhenaten had similar leonine links. In many depictions of the king, we see him in the classic Egyptian form of the sphinx.

Akhenaten as a Sphinx, worshipping the Aten; inscription from a talatat block from Amarna. Now in the Kestner Museum of Hanover, Germany. (Hans Ollermann, CC BY 2.0 )

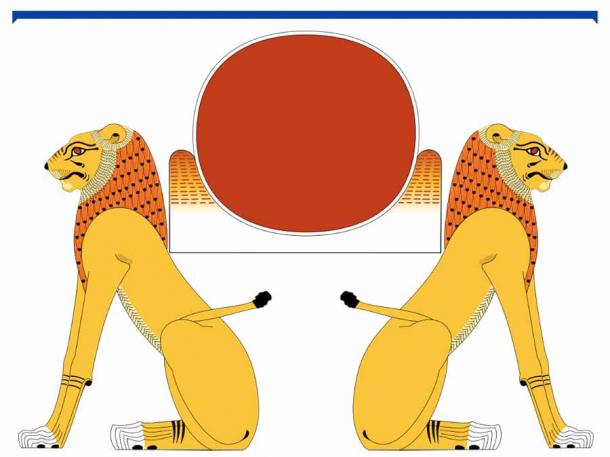

We also see the motif of two lions flanking the Akhet symbol, similar to the Torah cover designs. These Egyptian lions were called Aker, and they protected the king. They were Duaj (yesterday) and Sefer (tomorrow). Most fascinatingly, this latter word is still preserved in the word for the Torah Scroll, the Sefer Torah, which would mean, in Egyptian: “The Law for Tomorrow”. A Jewish scribe is also called a sofer.

The Aker symbol of the sun disk between two lions: Duaj (yesterday) and Sefer (tomorrow). The lion pair echoes the lithograoh by Schile, and also of every Torah scroll cover. (Jeff Dahl / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

By the Hand of God

During Yom Kippur, Jews place their lives metaphorically into God’s hands. The idea of God having hands is not new, and dates back to ancient Israel and Egypt. Today, we see this theme expressed in the protective amulet the hamsa hand. From the oldest section of the Torah, the Song of the Sea , we read Moses sang: “Your right hand, Lord, was majestic in power. Your right hand, Lord, shattered the enemy.” (Exodus 15:6). Many other of the oldest verses in the Torah speak of the strong hand of the Lord.

Egyptologist James K. Hoffmeier has even connected two Hebrew words to ancient Egyptian phrases from the time of Akhenaten. First, the Hebrew yad hazaqah (strong hand) is equivalent to the Egyptian hps, or “strong arm”, while the Hebrew zeroah netuya (outstretched arm) is equivalent to the Egyptian pr-a, or “the arm is extended” ( Israel in Egypt , 1996). We can see both ancient phrases many times in the Bible, such as Deuteronomy 26:8: “And the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with great deeds of terror, with signs and wonders.”

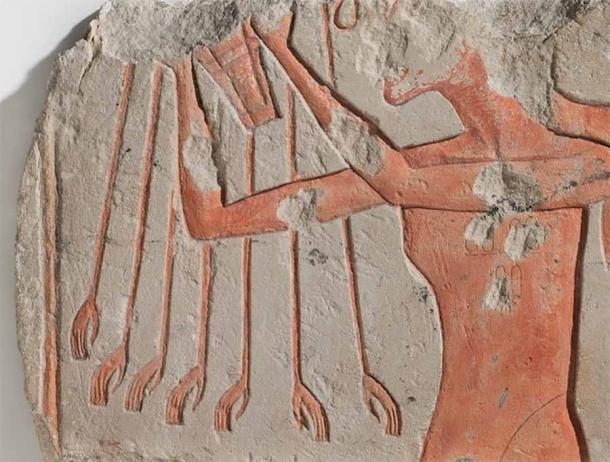

Akhenaten was obsessed with the hands of his deity, the Aten. It was the only human body part granted the Aten in art , and the only one referred to in inscriptions. For instance, we read from a decree of Akhenaten: “The beautiful living Aten…who constructed himself with his own two hands…” (Earlier Proclamation, Amarna Boundary Stelae).

The many hands of the Aten sun disk stretch down past the king, from an inscription on a limestone talatat block recovered from Amarna. Now in the Brooklyn Museum, Ascension #: 60.197.6. ( Brooklyn Museum )

We also find evidence that the Hebrew word zeroah (“outstretched arm”) derived from the Egyptian concept of the conquering arm of Pharaoh. In one of Akhenaten’s Foreign Letters, we read of the zu-ru-uh, meaning “the strong arm of the king.” If Akhenaten became Moses, the use of this Egyptian word in the Torah would make sense, and further serve to connect them.

Priests in White Linen

The appropriate clothing during this day is white linen. This symbolizes purity, and represents the spiritual cleansing that one should be seeking. One type of white linen outfit is called a kittel. The practice stems from the ancient Biblical ordinance for the High Priest to forgo his usual elaborate golden outfit (another connection to Akhenaten) on this holiest day of the year and dress only in white linen. This was so he could appear before the Ark of the Covenant as completely pure.

According to Leviticus 16:4: “He is to put on the sacred linen tunic, with linen undergarments next to his body; he is to tie the linen sash around him and put on the linen turban. These are sacred garments; so he must bathe himself with water before he puts them on.”

Many Jews have emphasized another theme associated with white clothing: the death of self, and the rebirth into new life during the Day of Atonement. The kittel, for example, is actually a burial robe, and far from being a morbid notion is actually meant to remind worshippers of their own symbolic death and rebirth under God’s redemption. This idea very likely originated from the concept of rebirth and new life represented in the Book of the Dead scrolls, and at Amarna (in modified form).

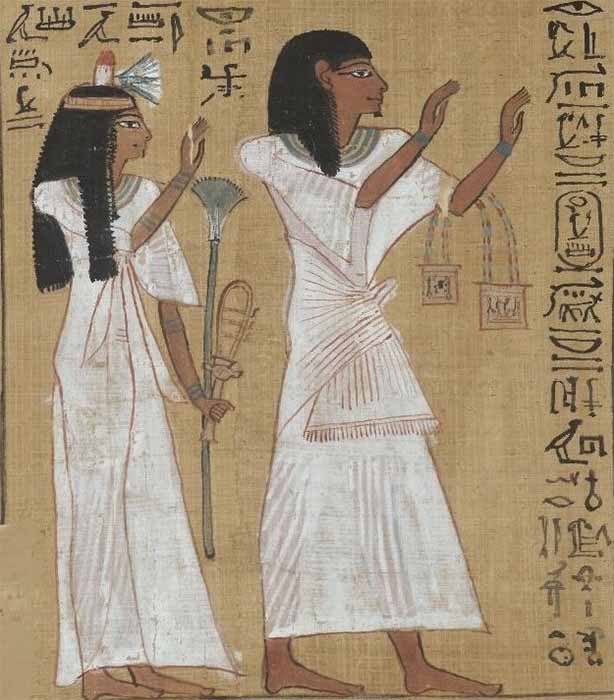

When we look at images from life at Amarna under Akhenaten, we see the king and his family dressed in very similar white linen garments. In fact, most people living in the city wore such garments. Egyptian priests in general were commanded to wear only pure white linen, a practice later adopted by Moses and his Israelite religion.

Full length white linen body garments worn my pious Egyptians when before the gods. Here they are worn by Hunefer and his wife in a vignette from his Book of the Dead scroll, now in the British Museum (EA 9901). They are pleated and sheer and are meant to represent the ritual purity of Hunefer. ( British Museum)

It is so fascinating to see Akhenaten and Nefertiti dressed in white linen garments while they worship the Aten, while modern Jews today still wear near-identical garments while worshipping the Lord, three millennia later.

There is yet another connection back to Amarna, concerning the extra commandment to bathe and wash. This practice was a common feature of Amarna life and religion. Akhenaten’s temples were full of washing basins and ritual stepped pools, and even the houses in Amarna sported lime-plastered washing areas (called “lustration slabs”) and even toilets!

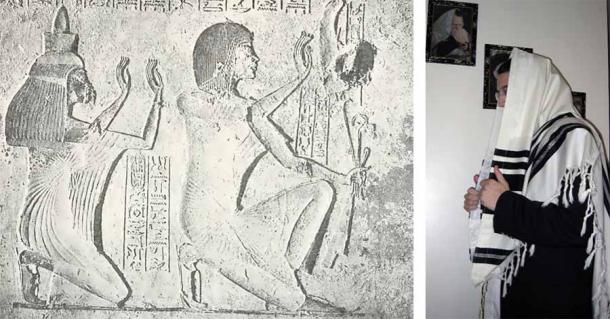

During the evening prayer service, called Kol Nidrei, it is customary for male Jews to wear the linen tallit prayer shawl. This is the only occasion that this special shawl can be worn at night, and draws our attention to its enigmatic origins. Described in the Torah (Numbers 15:38), I believe that it actually originates with the striped Pharaonic nemes headdress, seen most famously on Tutankhamun.

Left; Akhenaten’s uncle and general Aÿ (right) and his wife Tyi (left) wear white pleated linen outfits in a scene from their Amarna tomb (No. 25). (Plate I, “Aÿ and his wife Tyi”, from Davies, N. de G., The Rock Tombs of El Amarna: Part VI, Tombs of Parennefer, Tutu, and Aÿ. (London, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1908). Right; A Jewish Tallit, or prayer shawl. They are worn through all prayer services on Yom Kippur, and the only time of the year they are worn at night. They likely derive from the striped nemes headdress worn by all Pharaohs. ( Public Domain )

Curiously, the service Kol Nidrei means “all vows”, and refers to participants pleading with God to be forgiven for any vows they made the previous year but were unable to keep. This recalls Akhenaten’s penchant for making vows, his desire to keep those vows, and the presumed guilt he would have experienced were he ever to have, for some reason, broken them.

We read the King’s words directly from his Earlier Proclamation, Amarna Boundary Stelae: “Behold I am making an oath about it, saying “I shall make it (Amarna) as the Horizon for the Aten.” He later declares he will never leave the boundaries of his city, which belong entirely to the Aten: “Here is this genuine oath of mine … it is Akhet-Aten in its entirety. It belongs to my father, the Aten … I shall not ignore this oath which I am making for the Aten, my father.”

Shine On You Crazy Diamond

Associated with white linen was another resounding theme throughout Yom Kippur: light – God’s light specifically. For example, we read in Psalms 27:1: “The Lord is my light and my help; whom should I fear?” We also read Moses describe God’s face in Numbers 6:25: “The Lord make his face shine on you , and be gracious to you.” This verse is the oldest Bible verse ever found, inscribed on two small silver scrolls in Israel during the 7th century BC. The idea of a shining face of divine light harkens back to Amarna and Akhenaten, who was known for worshipping the light of his father, the Aten.

Let us look at the Yotzer Or Blessing (“Creator of Light”), the first blessing recited before the Shema during Shacharit, the Morning prayer service on Yom Kippur. There are many similarities to inscriptions from the tombs of Panehesy, his Second Prophet, Tutu, his chamberlain, and Ay, his uncle and general. Let us compare the Jewish prayer (in bold) to the Amarna inscriptions (in italics):

Blessed are you, the Lord our God, King of the universe.

Beautifully you appear from the horizon of heaven, O Living Aten, King who gives life,

Who forms light and creates darkness,

When your movements vanish, the land is in darkness, but the land grows bright when you are risen …

Who makes peace and creates all things,

Welcome in peace, lord of peace! You are the lord of all you have created.

The one who provides light for the earth, and for all who dwell upon it, with mercy,

For although you are far away, your rays are upon the earth, and you are perceived,

And in His goodness renews every day, constantly, the work of creation,

O Living Aten, who begets himself by himself every day! Every land is in festival when you appear!

Sunrise, Sunset

The exact start of Yom Kippur is marked by the setting of the Sun, and is precisely recorded by Rabbis. The image of Orthodox Jews praying as the sun sets behind them has now become a classic image of Yom Kippur. The reason behind this remains a mystery. The precise times of sunrise and sunset are vitally important to Jews, who schedule their prayers around them. These times are called zmanim in Hebrew, and are carefully calculated each year. They demarcate certain periods of time during which Jews can complete various commandments, or mitzvot, of the Torah.

The most noticeable feature of the zmanim is their discernment between dawn, sunrise, and even the period between them. Dawn is called Alos Hashachar, and sunrise is called Haneitz Hachama, when the actual sun disk is visible above sea level. Likewise, in the evening, Shkiyas Hachama is the moment when the sun disk disappears completely, and officially marks the end of the Jewish day. Noon, or mid-day, is called Chatzos, which echoes the three ancient aspects, or manifestations, of the Egyptian sun god: Khepri at dawn, Ra at noon, and Atum at dusk. It also curiously echoes the prayer times of King David: “Evening, morning and noon I cry out in distress, and he hears my voice.” (Psalms 55:17).

This focus on the light of the Sun and the disk of the Sun is eerily reminiscent of Akhenaten’s cult of the Aten. Most scholars agree that the Egyptian day began at dawn, before the rising of the Sun, rather than sunrise, especially at Amarna. We read in inscriptions: “Be adored when you rise in the horizon, O Aten!” and “Hail to you who rises in the sky and shines at dawn in the horizon of heaven!” and even “So that celebration may be made at your rising and your setting also.”

The appearance and disappearance of the sun disk itself, the Aten, was of prime importance to Akhenaten: when it moved through the akhet, or horizon, that magical place in the distance. The Bible shares this focus on morning, light, sunset, and celebration of the deity. For example, Psalms 5:3 states: “O Lord, in the morning you hear my voice, in the morning I prepare a sacrifice for you and watch.” Psalm 97:11 meanwhile says: “Light dawns for the righteous, and joy for the upright in heart.”

The idea of a sole eternal God who created light and life for the entire world was first introduced by Akhenaten, and this same idea permeates the earliest layers of Moses’ Torah. Akhenaten’s original ideas of truthful words, righteous actions, pure motives, and loving care – all subsumed under the rubric of divine light – remain key attributes of Judaism generally and Yom Kippur specifically. Three millennia ago, a rebel king became the world’s first monotheist, teaching truth, joy, light, peace, and righteousness. Remarkably, Jews today are still celebrating these same themes.

Top image: Painting, ‘On the eve of Yom Kippur’ by Jakub Weinles. Source: Public Domain

By Jonathon A. Perrin

Jonathon Perrin is a petroleum geologist who has helped excavate numerous prehistoric Native sites in Canada. With a degree in geology and archaeology, his passion is writing about ancient mysteries and uncovering the subverted truths of history. He is the author of Moses Restored: The Oldest Religious Secret Never Told , available in its brand new Second Edition as a print or e-book from Amazon.com. Visit his new site: www.jonathonperrin.com.

References

Abramowitz, Rabbi Jack, “Z’manim Explained,” OU Torah, (https://outorah.org/p/41921).

Assmann, Jan, From Akhenaten to Moses: Ancient Egypt and Religious Change . (The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2016).

Assmann, Jan, “Confession in Ancient Egypt,” In Destro, Adriana ; Pesce, Mauro (Hrsgg.): Ritual and ethics. Patterns of repentance. Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Second International Conference of Mediterraneum. Paris; Louvain 2004, pp. 1-12.

Assmann, Jan, “Conversion, Piety and Loyalism in Ancient Egypt,” In Stroumsa, Guy G. (Hrsgg.): Transformations of the inner self in ancient religions. Leiden; Boston; Köln 1999, pp. 31-44 (Studies in the history of religions; 83).

Dodson, Aidan, Amarna Sunrise: Egypt from the Golden Age to Age of Heresy (American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2014).

Dodson, Aidan, Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation (American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, 2009).

Ertman, Earl L., “Images of Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti in the Style of the Previous Reign,” University of Akron, In Causing His Name to Live, Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane, (Brill, Leiden, 2009) ( https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.memphis.edu/dist/4/463/files/2014/03/Ertman-29te95x.pdf).

Friedman, Richard Elliot, The Bible With Sources Revealed: A New View into the Five Books of Moses (Harper One, New York, 2003).

Hoffmeier, James K., Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism, (Oxford University Press, New York, 2015).

Jastrow, Morris Jr., and Max. L. Margolis, “Atonement, Day of,” In the Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906, ( http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/2093-atonement-day-of).

Kalimi, Issac, “The Historical Uniqueness and Centrality of Yom Kippur,” In TheTorah.com, (https://www.thetorah.com/article/the-historical-uniqueness-and-centrality-of-yom-kippur).

Kamring, Janice, “Telling Time in Ancient Egypt,” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000, February, 2017, ( https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tell/hd_tell.htm).

Markus, Rabbi David Evan, “Yom Kippur’s Circle Dance,” In My Jewish Learning, (https://www.myjewishlearning.com/rabbis-without-borders/yom-kippurs-circle-dance/).

Moran, William L. ( ed), The Amarna Letters (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1992).

Murnane, William J., Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt (Scholars Press, Georgia, 1995).

Osman, Ahmed, Moses and Akhenaten: The Secret History of Egypt at the Time of the Exodus (Bear & Company, Vermont, 2002).

Pendlebury J. D. S., The City of Akhenaten, Part III. London. Egypt Exploration Society. Memoirs of the Egypt Exploration Society 44 (London, 1951).

Redford, Donald B. Akhenaten: The Heretic King, (Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1984).

Ringgren, Helmer, “Light and Darkness in Ancient Egyptian Religion,” In Liber Amicorum: Studies in Honour of Professor Dr. C.J. Bleeker; Vol. 17 (Brill, Leiden, 1969).

Safren, Jonathan D., “Jubilee and the Day of Atonement,” In Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies, 107-113, 1997.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 17th, 2021

September 17th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: