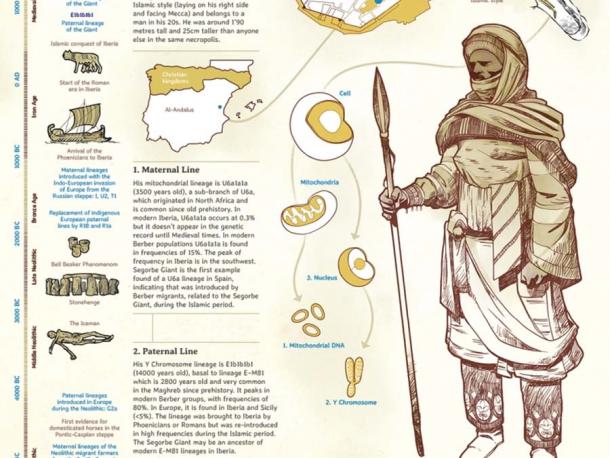

Genetic experts have completed a full sequencing of a DNA sample obtained from a 1,000-year-old skeleton unearthed in 1999 in an ancient Islamic cemetery near the village of Segorbe, Spain, which is located a short distance inland from the Mediterranean coastal city of Valencia. Nicknamed “the Segorbe Giant” because of his unusual height (74 inches or 190 centimeters), it seems this individual carried genes inherited from both the local Spanish population and from Moorish immigrants. The latter would have arrived sometime following the establishment of the Islamic kingdom of Al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century AD.

The study of the Segorbe Giant’s DNA was carried out by a large international research team, led by British scientists from the University of Huddersfield’s Archaeogenetics Research Group. The scientists published the results of their study in the journal Nature: Scientific Reports . The actual DNA sequencing was completed by Huddersfield researchers Dr. Marina Silva and Dr. Gonzalo Oteo-Garcia, who specialize in evolutionary genetics.

The Moorish immigrants were Arabs and Berbers who came to the kingdom of Al-Andalus from North Africa. The DNA analysis showed the Segorbe Giant was related to Berber immigrants on both his father’s and mother’s sides.

Nevertheless, his overall genetic makeup was more than half Spanish. This showed he came from an integrated community where North African Muslim immigrants and the local Spanish population lived side-by-side and interacted peacefully. A further chemical analysis proved he’d grown up in the community where he lived, meaning his North African ancestors likely arrived several generations earlier.

One of the most eye-opening discoveries to emerge from the genetic analysis was that the 11th-century Segorbe Giant shared no DNA with the modern settlers of the Valencia area. The Segorbe Giant’s people didn’t remain in the region over the long term, which confirms what historians studying medieval Spain already know about the tragic events that occurred in the Valencian region in the early 17th century.

When the Christians arrived in the area they expelled or killed many of the Muslims settled in the area for generations and soon enough this also included the Muslim converts to Christianity (the Moriscos or converted Moors).

An artist’s illustration of the Segorbe Giant along with genetic information about his maternal and paternal lines. ( University of Huddersfield )

The Segorbe Giant and the Expulsion of the Morisco Muslims

After the establishment of the Kingdom of Al-Andalus under the Umayyad Dynasty , Spain remained under Muslim control for more than 300 years. However, Christian campaigns to retake what had formerly been Christian land began to find success in the early 11th century.

In the Kingdom of Valencia where the Segorbe Giant lived, Muslims maintained political authority and military control until the end of the century . But eventually the Christian forces occupied the entire Iberian Peninsula, ending the Kingdom of Al-Andalus and putting Muslim settlers in Segorbe and elsewhere in a precarious position.

Relations between Christians and Muslims in the Spanish Christian kingdom of Aragon, which included the lands of the former Kingdom of Valencia, got worse over time. This was most distressing for Muslim communities, who were in a minority position without the political power and influence to control their own fates.

That lack of power and influence proved to have severe consequences. In 1525, a decree issued by King Charles I ordered all Muslims in the Kingdom of Aragon to convert to Christianity immediately, or face expulsion from the country (other Spanish kingdoms had issued such edicts earlier).

The majority did so. But the end of religious tolerance in Christian Spain was accompanied by increased suspicions about the true intentions of the former Muslims who remained within Spanish realms. In Valencia, where converted Muslims comprised about a third of the population, tensions ran especially high. In general, the Christian population comprised the upper and middle classes, while the Moriscos (Muslims who had converted to Christianity) were peasants and laborers.

Expulsion of the Moriscos at the port of Dénia, by painter Vincente Mostre. (Vicente Mostre / Public domain )

Finally, in 1609, the reigning Spanish monarch, King Philip III, took one of the most drastic steps imaginable. He ordered all the descendants of Moriscos to leave the Iberian Peninsula immediately. They were instructed to take only what they could carry with them, excluding any money, gold, or jewelry they might possess. If they refused to leave they would be subject to arrest and imprisonment, or possibly even worse.

Exactly how many Moriscos were forced into exile over the next few years is not known exactly, but the total number was certainly in the hundreds of thousands.

In the area around Valencia, the forced exodus was massive, and much larger than in other regions. This historical event explains why the Segorbe Giant’s DNA is so different from modern residents of the location where he was buried.

“The decree of expulsion of Moriscos from the Valencia region was followed by the resettlement by people from further north, who had little North African ancestry, thereby transforming the genetic variation in the region,” explained Dr. Oteo-Garcia in a University of Huddersfield press release .

“The impact of this dramatic change in population, resulting from a brutal political decision hundreds of years ago, can finally be witnessed directly using ancient DNA , as seen here in the ancestry of the ‘Segorbe Giant’ and his contemporaries,” added Dr. Silva, who is currently employed at London’s Francis Crick Institute.

The effects of the forced expulsion of all Muslim converts to Christianity in and around Valencia were significant. With so many agricultural workers and laborers suddenly gone, the economy contracted, and the region experienced hard times. Even with the importation of workers from elsewhere, inhabitants in the region suffered. For some this is exactly what they deserved for letting their bigotry and intolerance overcome their sense of decency and compassion.

Professor Martin Richards, director of the Evolutionary Genomics Research Centre, was one of the main researchers involved in the study of the Segorbe Giant’s DNA. ( University of Huddersfield )

Revealing History Through Genetic Analysis

The data uncovered from the deep genetic analysis of DNA often reveals fascinating details about the migratory patterns of ancient peoples. That is certainly the case with the Segorbe Giant, as his DNA proved that he was descended from Mediterranean migrants who arrived to help build a stable and prosperous Islamic kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula in the medieval period.

The termination of the Segorbe Giant’s genetic line also reveals important details about past events. While archaeological and anthropological knowledge is most often advanced by what scientists do find, in this unusual instance it was advanced by what they didn’t find. The impact of a long-ago crime against humanity lingers, revealed through the diminished diversity of modern Valencia’s genetic heritage.

Top image: An artist’s illustration of the Segorbe Giant along with genetic information about his maternal and paternal lines. Source: University of Huddersfield

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 28th, 2021

September 28th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: