From Wear’s War

…the Americans forced the defendants to watch US-made “documentary” films of German atrocities that deceitfully included scenes of corpses filmed in the wake of Allied air raids on German cities and factories.

After Germany’s defeat in WWII, the Nuremberg and later trials were organized primarily for political purposes rather than to dispense impartial justice. Wears War brings to you each week a quote from the many fine men and women who were openly appalled by the trials. All of these people were highly respected and prominent in their field, at least until they spoke out against the trials.

Daniel W. Michaels reviewing David Irving’s book Nuremberg: The Last Battle:

As Irving shows, the victorious Allies who sat in judgment at Nuremberg were guilty of many of the same actions or crimes for which they tried (and hanged) the German defendants. Indeed, the Allies very probably outdid the Germans in crimes and atrocities.

Irving cites, for example, the British-American fire bombings of Dresden, Hamburg and other German cities, killing tens of thousands of civilians at a time, the “ethnic cleansing” mass expulsion of German civilians from eastern and central Europe, of whom some two million perished or were killed, the widespread summary shootings of German prisoners, and the Allies’ use of hundreds of thousands of German prisoners as slave laborers. He also cites such lesser-known incidents as the sinking by British aircraft during the war’s final days of a clearly marked German Red Cross refugee ship, the Cap Arcona, killing 7,300 refugees, mostly women and children.

At the Yalta conference in February 1945, Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin agreed to use millions of German POWs and German civilians as slave labor in Soviet Russia, France, and Belgium as partial “reparations in kind.” Jackson was shocked to learn that the Soviets wanted five million of these forced laborers, and France two million. (No final accounting has ever been made of the total number deported to the USSR for this purpose, or of the number who ever returned). President Roosevelt endorsed this policy, which was in blatant violation of international law, concerned only about the possibly negative impact on public opinion and election prospects back home.

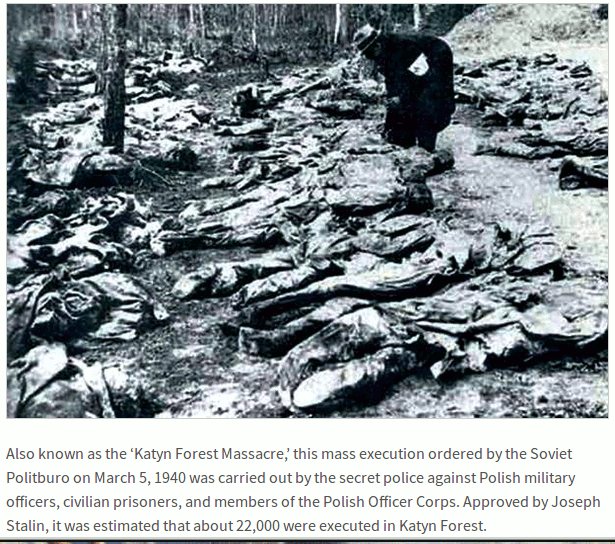

In some cases, the Nuremberg defendants were charged with or held guilty of crimes that were actually committed by the Allies. Most noteworthy, perhaps, is the massacre, at Katyn and elsewhere, of some 11,000–15,000 Polish officers and intellectuals. At Nuremberg Soviet prosecutors presented seemingly persuasive evidence of German responsibility for this crime, and several Germans whom a Soviet court had found guilty of these killings were publicly hanged in Leningrad. It was only decades later that Soviet officials formally acknowledged that the massacre had been carried out by the Soviet secret police, acting on Stalin’s orders.

Predictably, the Allies grandly exploited the Tribunal for propaganda purposes. As Irving relates, the Americans forced the defendants to watch US-made “documentary” films of German atrocities that deceitfully included scenes of corpses filmed in the wake of Allied air raids on German cities and factories. Some of the German viewers spotted the deception, and one former Messerschmitt worker said he even recognized himself in the film.

In these unprecedented proceedings, the Allies discarded basic principles of Western jurisprudence, perhaps most notably the well-established principle that in the absence of a law there can be neither crime nor punishment – nullum crimen sine lege, nulla poene sine lege. Instead, the Tribunal established new laws for the occasion, which were applied not only retroactively, but uniquely and exclusively to the German defendants. The Allies thus refused to consider the German defense argument of tu quoque or “you too” – that is, punishing the German defendants for actions that the Allies themselves also carried out.

The Tribunal rejected defendants’ pleas of obeying higher orders, even though, as Irving points out, precisely this had been affirmed as a valid defense under both British and American military law. Article 347 of the American Rules of Land Warfare, for example, specifically declares:

Members of the armed forces are not punished for these crimes, provided they were committed on the orders or with the permission of their governments or commanders.”

The Tribunal’s procedures, which were a blend of Allied procedures, differed markedly from German practice. In Germany, as in most of continental Europe, the court’s primary objective is to ascertain the truth. However, the Nuremberg Tribunal adopted a version of the American confrontational system, in which each side introduces only the evidence that benefits its own case. But because the Allies had confiscated all pertinent German documents and records, and refused access to them by the defense attorneys, the prosecution had a tremendous advantage over the German defendants.

Source: The Journal of Historical Review, January/February 1998 (Vol. 17, No. 1), pages 38-46.

Daniel W. Michaels retired from the US Department of Defense after 40 years of service. He was a Columbia University graduate (Phi Beta Kappa, 1954), and a Fulbright exchange student to Germany (1957). He resided in Washington, DC prior to his death.

Source Article from http://www.renegadetribune.com/allies-outdo-germans-crimes-atrocities/

Related posts:

Views: 2

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 22nd, 2018

March 22nd, 2018  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: