One of the great mysteries of the New Testament is the Star of Bethlehem and the magi (the three kings or wise men) who “followed” the star to pay their respects to the newborn Jesus. Most historians date the birth of Jesus between 7 BC to 2 AD. Over time, astronomers and theologians theorized the star was everything from a configuration of celestial bodies to a bright supernova. However, the only primary source known to date, from ancient China , suggests that it was a comet. But does this evidence finally confirm the true nature of this celestial body? And who were the magi of the Bible? Where did they come from? What were their intentions? And how can all these questions be answered with a comet or a star?

Chinese Comet of 5 BC May Have Been the Star of Bethlehem

In March of the year 5 BC, the Chinese observed and recorded a “broom comet” in the constellation of Aguila (eagle) in the zodiac of Capricorn. Naturally, the Chinese and other Far Eastern records have been closely examined to find if any of their observations reveal celestial objects that were discovered around the time of Jesus . The recorded observations of the Chinese are known for their accuracy, and because the Chinese were non-Christians, their records were not tampered with by early Christians to establish papal authority or the existence of Jesus, something done to some early Christian texts.

The Chinese observation of a possible comet or nova, is noted in a book called the Ch’ien-han-shu, which, according to astronomer Mark Kidger, states the following: “In the second year of the period of Ch’ienp’ing, the second month, a hui-hsing appeared in Ch’ie-niu for more than 70 days.” The second month in the Chinese calendar in the year 5 BC is equivalent to March 10 to April 7. Ch’ie-niu is the Chinese constellation that includes Alpha and Beta Capricorni. Hui-hsing literally means “broom stars.” These were bright comets with tails that swept through the sky. Seventy days is a long time and would have been more than enough time for the magi to journey to Jerusalem and ultimately Bethlehem.

‘Broom stars’ were great comets that swept through the sky. ( Johnster Designs / Adobe Stock)

It must also be taken into consideration that the monsoon season in China is roughly between April to September. This may have shortened the observation period for the Chinese. Nevertheless, the comet’s observable duration and clarity was most likely longer in the arid regions of the Middle East. The Chinese comet isn’t the only ancient source that can be examined to discover information about the Star of Bethlehem. The writings of early Church Fathers and ancient historians also provide some clues.

The Early Church Fathers Views on The Star of Bethlehem

Writings from two early Church Fathers advocate that the Star of Bethlehem was a comet and that the magi came from Parthia. The Church Father Origen suggested in the 3rd-century-AD work Contra Celsus that the star followed by the magi had properties similar to a comet or meteor. It is thought that the magi were ambassadors for the royal families of Parthia who ruled Persia at that time. Julius Africanus, another 3rd-century-AD Church Father, wrote in The Ante-Nicene Fathers , “How is this, say they, that wise men of the Persians are here, and that along with them there is this strange stellar phenomenon?”

The magi or three kings who followed the Star of Bethlehem to find the new born Jesus. Source: Mapa original: Juan de la Cosa / Public domain

Over time the magi came to represent something much more than ambassadors. They were transformed into all-knowing “wise men” who set out to honor the new king, Jesus, and some believe they may have been kings themselves. Many Christians believe their journey to Bethlehem to worship Jesus parallels the journey of everyday Christians who seek out the wisdom of the Lord.

The journey of the magi to honor Jesus was long and filled with potential harm from Herod. However, through the help of God, they returned safely home. It is also believed that they were not Jewish. They were perhaps the first Gentiles to worship Jesus, but their journey may have been influenced by Jews living in the Parthian Empire .

In the past, most historians focused mainly on the astrological and astronomical skillset of the magi while overlooking their political motives. For example, the antagonistic relationship between Rome and Parthia most likely played a role in the motives of the Magi, or the brief period of peace that followed Augustus’ stable reign.

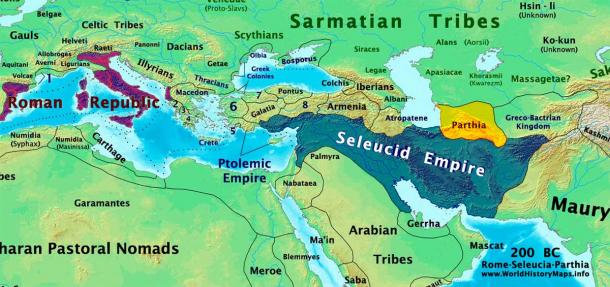

Rome vs Parthia

Long before the birth of Jesus, Parthia and Rome clashed over the territories that lay between them. Since Herod was a puppet ruler of the Roman Empire, the rulers of Parthia relished the idea of Herod being deposed by a new king of the Jews. From the New Testament we know that the Jews rejected Jesus as the Messiah because they were searching more for a warrior king, similar to David, who would free Judea from Roman tyranny. It should not be much of a stretch to believe that the magi similarly hoped for a Jewish revolution. Although it is not often mentioned, the motives of the magi may have been political as well as religious.

Rome, Parthia and Seleucid Empire in 200 BC. Soon both the Romans and the Parthians would invade the Seleucid-held territories and become the strongest states in western Asia. (Talessman / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Rome desperately wanted to recreate the empire of Alexander the Great and needed to conquer Persia to do so. Equally, Parthia desired to recreate Alexander the Great’s empire and needed to conquer Judea and Greece to achieve that goal. Both were under Roman control. As a minimum, Parthia desired a buffer zone or friendly ally between them and the ambitious Romans. Judea would have been an ideal ally for them.

Also significant was that Herod and his brother were named as tetrarchs by the Roman leader Marc Antony and asked to support Hyrcanus II. Hyrcanus II was later deposed by his nephew Antigonus, who had help from the Parthians. Herod then bribed Marc Antony to restore his tetrarch status and to make him king of the Jews. G. A. Williamson states, “Herod was never at a loss for appropriate gifts, which in his approaches to Antonius were on a vast scale. Antonius had a political motive too: Rome could never tolerate a Jewish king who owed his throne to their most dreaded enemies, the Parthians.”

Rome helped Herod defeat Antigonus, who was executed, and the Roman senate named Herod king of the Jews. Thus, the magi as representatives of Parthia most likely would have raised Herod’s suspicions. Matthew 2:3 tells us that the magi asked Herod where the newborn king of the Jews was. But Herod did not kill the magi. Instead, he attempted to use them to find the location of the new upstart, Jesus, that was a threat to his crown.

Jesus being taken from Herod to Pilate to be crucified. (James Tissot / Public domain )

As far as we know, the magi did not return to honor Jesus after their first visit and were warned by God not to return to Herod, which may explain why they did not return to Jesus for future visits. It remains unknown how upset Herod was when the magi did not return. More than likely, he was not happy, and would perhaps have executed them if they had returned at a later date.

Why the magi worshiped Jesus remains unknown. Some theologians suggest that they desired to worship the future religious authority of Judea. We know that the Jews were expecting more of a ‘deliverer from Rome’ and less of a prophet. Therefore, it must be questioned why the magi would be seeking something other than what the Jews were hoping for. Regardless of false Hollywood productions, Persian kings were not considered gods by their subjects. Therefore, it should be wondered why the magi would honor a Jewish king any differently.

The Parthian Magi: Who Were They and What Were They After?

It is very plausible that the magi knew very little about Judaism. Because they were the first Gentiles to worship Jesus, over time they earned a reputation for being wise and all knowing. But the nativity narrative in Matthew suggests that the magi were more likely ambassadors of powerful rulers. Matthew informs us that the magi lost track of the Star of Bethlehem and had to ask King Herod about the birth of Jesus.

The two most likely places for the magi to have come from are Babylonia or Persia. Both make an excellent choice because of their long history of observing the skies, and the fact that large Jewish populations were living in those regions at the time. The Greek geographer Strabo of Amaia (64 BC–ca. 23 AD), who was alive when Jesus was born, gives a description of the life of the Babylonian astronomers in The Geography of Strabo 16.1.6.

In Babylon a settlement for the local philosophers, the Chaldaeans, as they are called, was created specifically for them. The Chaldaeans were mostly focused on astronomy. A few professed to be genethlialogists (writers of horoscopes). There is also a tribe of Chaldaeans, and a territory inhabited by them in the region of the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Sea. There are also several tribes of Chaldaean astronomers.

Additionally, we know from Strabo that there were several settlements from around the time of the nativity that specialized in astronomy that would have been aware of new celestial occurrences. Relationships between the Jews and the Parthians were much better than with the Romans who occupied Judea. There were also Jewish settlements close to the Chaldaean settlements. Paul Johnson, in, A History of the Jews , writes:

“As Greek ideas about the one-ness of humanity spread, the Jewish tendency to treat non-Jews as ritually unclean, and to forbid marriage to them, was resented as being anti-humanitarian; the word ‘misanthropic’ was frequently used. It is notable that in Babylonia, where Greek ideas had not penetrated, the apartness of the large Jewish community was not resented—Josephus said the anti-Jewish feeling did not exist there.”

Therefore, the Jews living in the east had a much easier time getting along with local governments than the Jews living in heavily Roman-influenced Judea. This was most likely because they considered Judea as their chosen land and the Romans as intruders. Persian leaders were also on better terms than the Romans with the Jews. This was aided in part because Cyrus the Great liberated them from Babylonian rule, and later helped to rebuild Solomon’s Temple, which was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar II in 587 BC.

Further enhancing the relationship between the Jews and the rulers of Babylonia and Persia was the fact that the Jews were not on friendly terms with the Parthian’s rivals in the region, the Romans. The Parthians dealt a humiliating defeat—they captured the Roman Aguila (eagle) standard—to the Roman leader Crassus, killing him in the process at the battle of Carrhae in 53 BC. This defeat halted Roman imperial expansion into Mesopotamia. If a new Jewish king was about to be born in Judea, with the blessing of Augustus, the magi would want to be on friendly terms with him to prevent future Roman aggression.

Augustus’ role in the Nativity may be greater than the ordering of a census at the time of Jesus’ birth—this was also a time of peace known as the Pax Romana , and Parthia was benefiting from Silk Road trade with the Romans. It was in their best interest to remain on good terms with Augustus—he was also benefiting from the Pax Romana by avoiding civil wars and forming a military junta of generals. This gave Augustus the full might of the Roman army at his disposal.

Left: Augustus silver denarius with Capricorn c. 16 BC courtesy of A. Marinescu, Vilmar Numismatics LLC Right: Augustus silver denarius with comet tail pointing upwards 19-18 BC courtesy of Roma Numististics

Augustus Caesar Liked to Use Comets For Personal Propaganda!

Some Star of Bethlehem enthusiasts maintain the star could not have been a comet because comets are considered evil omens. However, that is not true. Ancient sources related that Augustus liked to use comets for propaganda. Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), a Roman author, naturalist, philosopher, naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian tells of Augustus’s fondness for comets.

Pliny wrote in the encyclopedic Natural History about Augustus’s interpretation of a very brilliant comet observed shortly after Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC, and just before Augustus dedicated the Olympic games to Venus. Augustus used this comet to connect its appearance with his family in their claim of divine origin as direct descendants of Venus. Pliny wrote:

“In one only place of the whole world, namely, in a Temple at Rome, a Comet is worshipped: even that by Divus Augustus Caesar himself was judged fortunate to him. Who, when it began to appear, acted in Person as Overseer in those Games which he made to Venus Genetria, not long after the Death of his father, Caesar, in the College by him erected.”

After this, Augustus honored Venus, who he used to justify his reign by displaying comets on his royal coins. He also portrayed his zodiac Capricorn on some of his other coins. At a time when coins were the Facebook pages of important people, the magi, along with anyone in the Roman Empire who used coins, may have connected comets and the zodiac of Capricorn as an occasion for Augustus to promote a new ruler in the empire. The fact that the Chinese comet was observed in the constellation of Aquila was also symbolic of the Roman standards captured during the battle of Carrhae. It was returned by the king of Parthia to Augustus in 20 BC in a gesture of good will.

We will most likely never know what the comet of 5 BC looked like, other than that it was a “broom comet.” Its tail somehow pointed the magi to Judea, and they may have seen this event as an omen that a new king of the Jews was soon coming to power. Equally intriguing is the fact that Herod was in ill health at the time, and close to death. He most likely died a year later in 4 BC. I’m always discovering new information about this topic, and currently writing a book, The Star of Bethlehem, which will explore many new and interesting discoveries that were occurring in the sky the same time the comet was observed that had even more symbolic meaning in Judaism.

Top image: The magi or three kings who followed the Star of Bethlehem to find the new-born Jesus. Source: Pawel Horazy / Adobe Stock

By Robert Weber

References

Johnson, Paul, A History of the Jews (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), 134.

Kidger, Mark, The Star of Bethlehem: An Astronomer’s View (Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1999), 235.

Origen, The Ante-Nicene Father, Translations of the Writings of the Fathers down to A.D. 325 Vol 4 , (Buffalo: C.L. Pub. Co., 1885), 422.

Pliny the Elder, Holland, Philemon, Pliny’s Natural History in Thirty-Seven Books (London: Barclay, 1847-49), 65.

Roberts, Alexander et al., The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers down to A.D. 325 . Vol. VI, (Grand Rapids (MI): Eerdmans, 1957), 129.

Strabo, The Geography of Strabo Vol. 7, ( Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961), 203.

Williamson, G. M. The World of Josephus (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1964), 78.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 18th, 2020

August 18th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: