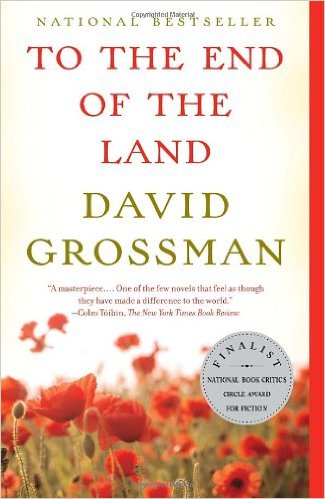

David Grossman is a very prominent and well-respected “liberal Zionist.” The Israeli writer recently wrote an essay for The Guardian in which he criticized Benjamin Netanyahu’s leadership. Grossman’s latest novel, To the End of the Land, was published in 2008 to high praise, almost reverence. I purchased the book last month. A careful reading suggests that Grossman still probably has a lot of emotional work to do. To the End of the Land is nationalistic. It’s also racist against Arabs—in its own special, strange, and chaotic way, which still manages to be completely banal at the same time. Here, in this short review, I will discuss his book and provide a few of my criticisms.

The main character is a middle-aged Israeli woman named Ora. She is extremely upset. Her son, Ofer, has finally finished up his mandatory military service, but after being home for only a few days, he gets called back. Ora and Ofer had planned to go on a mother-son hiking trip. Now he can’t go, and Ora is devastated. Then, horribly, she learns that her son hasn’t really been called back— he has, in fact, volunteered. Apparently, the thought of the mother-son trip was so grim and oppressive, he decided to reenlist.

Ora goes on the trip anyway. She’s newly single (her husband has recently left her). So, she brings along a lonely old boyfriend from her past, a dysfunctional male named Avram. The bulk of the book takes place on their trip. They’re walking along a path, through a nature reserve in Israel. As they hike, Ora tells Avram all about her family. Unfortunately, it feels like Ora’s spoken reminiscences, as well as her internal monologue about her two sons drag on endlessly, for hundreds of pages. Reading these passages was incredibly boring for me, and I felt like I had contempt for this nervous, intellectually limited woman. The book is 650 pages long, and I would recommend to Grossman that, going forward, he write short stories.

Grossman actually does a good job illustrating how distressed Ora is. Because there’s a military draft, the state can take her sons, and put them in danger. In this sense, I felt sorry for Ora. It certainly constitutes a form of violence against women, I think, for the government to seize teenage boys, and use them for war games.

While some parts of the book were interesting, I felt that Grossman’s treatment of the Palestinians was too simple. There’s an extended passage at the beginning of the story about Ora’s driver, a man named Sami. This made me think of the movie Driving Miss Daisy. (Ora’s family is middle-class, and they can afford to have a Palestinian driver who is on-call, 24 hours a day.) Grossman did a nice job describing Ora’s ambivalent feelings towards Sami. The character of Sami, however, is two-dimensional. Sami is sometimes charming, sometimes macho. At one point, he is taking care of a sick Palestinian boy (a relative) and when the little boy suddenly vomits, Sami punches him. Sami also speaks disparagingly of this mentally disabled boy.

Then, it gets worse: Although the boy is about seven years old, and has just vomited heavily, a Palestinian woman breastfeeds him. To the majority of mainstream readers, this would seem disgusting. I doubt that Grossman ever witnessed this particular (weird) sequence. So why put it in? He makes the Palestinians seem primitive.

Grossman also has too much reverence for the dream of Israel. During the nature walk in the story, there are lots of descriptions of beautiful plants… We learn that, years ago, Avram had been a prisoner of war, and was tortured in Egypt. Upon his release:

…he [Avram, in a semi-conscious state because of his torture wounds] was opening his eyes wide. A cold, strange spark shone out of them.

“Is there… Is there an Israel?”

I can’t relate to this. I also felt that Ora the mother, as described in one of the book’s many flashbacks, had brainwashed her son:

What do you tell a six-year-old boy, a pip-squeak Ofer, who one morning, while you’re taking him to school, holds you close on the bike and asks in a cautious voice, “Mommy, who’s against us?” And you try to find out exactly what he means, and he answers impatiently, “Who hates us in the world? Which countries are against us?”

Resignedly, she caves in and lists all the Arab countries that “hate” Israel. I felt this was unnecessary. She reinforces an overly simplified, very scary world view.

Ultimately, the book is a tragedy, because Ofer, the son, grows up and engages in explicitly criminal behavior while he’s in the army. Ora learns that Ofer has participated in an operation during which an older Arab man was locked inside a large refrigerator—a meat locker— for two days, and was almost killed as a result. Ofer, in an adolescent trance, didn’t take the initiative to release the man, or even to ask a supervisor, or another soldier, about the man. This part of the book was honest and sensitive. It could have been a self-contained short story.

Unfortunately, I can’t recommend To the End of the Land. I think Grossman intended his novel to be a love letter to Israel, warts and all. For me, it was too tedious to wade through the long descriptions of the nature area, and the endless, mundane flashbacks about Ora’s family. And, as stated earlier, the descriptions of the Palestinians are a little bit animalistic. I think that many readers of this site would be angered by this book.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2015/11/grossmans-letter-israel

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 30th, 2015

November 30th, 2015  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: