The economic fallout of the Covid-19 lockdowns has created the worst humanitarian crisis in recent history. Numerous surveys have revealed the sheer gravity of this unfolding catastrophe in India and the world. Its starkest symptom is mass starvation, which is once again stalking the land.

In this important series of articles for Covid Response Watch researcher and journalist, Sajai Jose explains the context, the trends and prognosis of hunger in India.

Locked down on empty stomachs: India’s accelerating hunger crisis

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the nation on August 15th, his 88-minute long speech sidestepped a sobering fact – that the nation of 1.3 billion that he governs is going through the worst economic and humanitarian crisis in its history. Instead, in a textbook illustration of demagoguery, Modi declared that the two major challenges faced by India were “terrorism and expansionism,” a veiled reference to India’s two neighbours, Pakistan and China.

The Prime Minister’s speech hardly mentioned the grim reality that was being endured by millions of Indians on the country’s 75th Independence Day – of severely reduced incomes, widespread unemployment, and increasingly, acute hunger. For good reason, perhaps, because survey after survey has confirmed that this crisis is in large part his own government’s doing; specifically through the massive disruption caused by its Ill-conceived -and worse-implemented- national lockdown in March 2020.

When the Prime Minister did touch upon the crisis, as when he brought up India’s chronic malnutrition problem, it was only to announce the launch of his government’s rice fortification programme. Ironically, recent research indicates that “compulsory food fortification is wasteful, ineffective and potentially harmful to human health.” Another analysis revealed the lucrative business that is rice fortification, suggesting that the government’s move was designed to benefit private players.

The next day, at a lavish breakfast hosted for Tokyo-returned Indian Olympians, the PM urged all of them to visit 75 schools each in the next two years to create awareness about malnutrition. It provoked one angry Twitter user, to respond: “It’s not like people suffer from malnutrition because they aren’t aware that they should eat more. You’re the prime minister. Feed people!”

India is the hardest hit

While the crisis is global, India is among those nations hit hardest. An analysis by the Pew Research Center estimated that in India alone, around 75 million people fell into poverty (people who live on $2 or less daily) last year. India accounts for nearly 60% of the global increase in poverty in 2020.

The study highlighted how from 2011 to 2019, the number of poor people in India had dropped from 340 million to 78 million. If the trend had continued, that number would have fallen further to 59 million last year. But thanks to pandemic-related disruptions, it is instead projected to rise to 134 million.

Another study, by the think-tank Brookings Institution, estimates that up to 144 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty by the impact of pandemic-related disruptions. The study puts India at the top of the list of countries where extreme poverty is likely to rise the most.

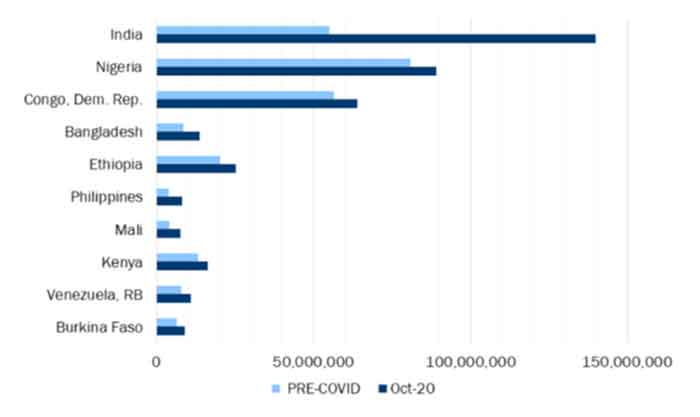

Figure 1; Countries with largest likely increases in extreme income poverty headcounts compared to baseline, 2020 (absolute numbers of people)[1]

According to Homi Kharas of Brookings, given the fact that the Indian economy is experiencing one of the deepest recessions in the world, “far and away the biggest impact is likely to be felt in India. India recently gave up its title as the country with the largest number of extreme poor to Nigeria but will reclaim its title this year, adding 85 million people to its poverty rolls in 2020.”

According to the World Bank, global extreme poverty rose in 2020 for the first time in over 20 years thanks to Covid-19-related disruptions. Up to 124 million more people have already been pushed into extreme poverty as a result of these disruptions, with the total expected to rise to as much as 163 million by the end of 2021. It further predicts that almost half of the new extreme poor will be concentrated in South Asia, a region already struggling with extreme poverty.

Similarly, the International Monetary Fund estimates that India would account for 40 million of the 80-90 million people expected to be pushed into extreme poverty (or 44.4% of the total) due to the impact of the pandemic-related disruptions.

Table 1: Global estimates of poverty induced by pandemic-related disruptions*

| Organisation | New poverty worldwide | Impact on India |

| IMF | Between 80 – 90 million | India will account for 44% of the newly poor |

| World Bank | Between 119 – 124 million | Half of the new poor will be in South Asia, the bulk of them in India |

| Pew Research Centre | Up to 134 million | Up to 75 million newly poor |

| Brookings | Up to 144 million | Up to 85 million newly poor |

*The number of people estimated/projected to be newly pushed into poverty by pandemic-related disruptions, calculated against pre-pandemic projections. Poverty here refers to people living on $ 2/day or less – which the World Bank classifies as ‘extreme poverty’.

Lockdown as body blow

India’s economic and employment situation was already at a historic low point when it was dealt a body blow by the national lockdown in March 2020. The majority of the population was already in dire straits nutritionally too when the lockdown hit them.

The pre-pandemic data is revealing. The National Sample Survey Office’s periodic labour force survey (PLFS) report for 2017-18 had revealed the country’s unemployment rate to have been the worst ever in 45 years. The survey’s findings reflected so poorly on the government –it being the first such survey after the disastrous move of demonetization – that it refused to release them, forcing two expert members of the National Statistical Commission to resign in protest. The Consumer Expenditure Survey of 2017-18, which revealed that for the first time in more than 40 years ‘real’ per capita household expenditure in India had fallen, suggesting a rise in poverty and food insecurity, was similarly buried.

Then the lockdown happened. This abrupt shutdown of a nation of 1.3 billion people rendered nearly 140 million of them jobless, as estimated by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. It reduced India’s GDP growth for the April-June 2020 quarter to minus 23.9% – the most severe impact suffered by any major economy. India’s GDP shrank by 7.3% last year, the worst performance of the economy in any year since Independence.

Then the lockdown happened. This abrupt shutdown of a nation of 1.3 billion people rendered nearly 140 million of them jobless, as estimated by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. It reduced India’s GDP growth for the April-June 2020 quarter to minus 23.9% – the most severe impact suffered by any major economy. India’s GDP shrank by 7.3% last year, the worst performance of the economy in any year since Independence.

The full extent of the impact of such a sudden, all-pervasive and enduring shock on the working population that form India’s majority, is incalculable. Various surveys conducted in the aftermath of the lockdown hinted at the sheer scale of misery and hardship visited on them by this callous move.

A Union health ministry survey found that the lockdown had “triggered food insecurity across Indian households, with people eating less than before and even skipping meals. Nearly 44 per cent of those reached for a response were either curtailing their daily food intake or skipping one meal.” These findings were consistent with those of several other surveys conducted in this period, including one by the Right To Food Campaign held across 159 blocks in Jharkhand, which found that a large number of beneficiaries – including nearly 70% of under-3 malnourished kids – did not receive supplementary nutrition from January to June this year.

One of the most detailed such studies, a 12-state survey by Azim Premji University, found that the situation remained dire a year after the lockdown. It revealed that the pandemic-related disruptions had pushed a shocking number of Indians – 230 million – below the national minimum wage poverty line (Rs 375 per day, as recommended by the Anoop Satpathy committee).

A worsening hunger crisis

In recent years, India has become self-sufficient when it comes to grain production. Media reports indicate that Food Corporation of India procurement has far exceeded the buffer stock limit to reach record levels. At the beginning of 2021, it was estimated, India had foodgrain reserves 2.7 times more than required, creating a “massive problem of plenty.”

The Food Corporation of India, which is responsible for procurement and storage of grain, along with the Public Distribution System (PDS), form the backbone of the country’s food security. Considered the largest food distribution machinery of its type in the world, the PDS consists of a network of more than 400,000 Fair Price Shops (FPS), and is said to distribute commodities worth more than Rs 15,000 crore to about 16 crore families each year.

These figures may seem impressive, but the reality is that India remains home to the largest undernourished population in the world. Some 189.2 million Indians, i.e. 14% of the population, are undernourished, forming a quarter of all undernourished people worldwide.

The 2020 Global Hunger Index ranked India 94th out of 107 countries with hunger. With a score of 27.2, only 13 countries fared worse than India, which has a level of hunger the Index classifies as ‘serious.’ The Global Nutrition Report, which reports on country-level progress towards global nutrition targets, puts India in the category of countries that are not on track for meeting the listed targets.

The government’s own data confirms these trends. The latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) found that there was no improvement in chronic malnutrition or stunting among children below five years, while acute undernourishment or wasting worsened in a majority of the surveyed states in the last half-a-decade. The Niti Aayog’s sustainable development goals (SDG) index, released in June 2021, revealed that 11 states, including the more economically developed ones like Maharashtra and Gujarat, scored less than 50 out of 100 in their stated goal of reaching zero hunger.

A government-made disaster

India’s per capita income has more than tripled in the last two decades, and yet the minimum dietary intake of its citizens fell. The gap between the incomes of the rich and the poor has only increased during this period of high economic growth. Around 21.25 percent of the population lives on less than Rs 150 (US$ 2).

The irony is that India saw the most people moving out of poverty – some 270 million people- between 2005 and 2016, as reported by the Multidimensional Poverty Index. However, at least since 2016, India has been sliding down when it comes to poverty, hunger and income inequality. A 2019 Niti Aayog report showed that poverty went up in 22 states in 2019 compared to 2018; 24 saw hunger go up and 25 saw income inequality go up during the same period.

The Business Standard columnist Prasanna Mohanty’s take on this government-made disaster is worth quoting in full. “It being the chief think tank of the Government of India, it is surprising that the Niti Aayog does not explain why there is a fall in such critical indices as poverty, hunger and income inequality… Ironically, the government never acknowledged the Niti Aayog’s report nor took corrective measures. It had done the same for growing unemployment and slowing down of the economy before the pandemic.”

Mohanty further says, “The inept and callous handling of the pandemic and the untimely and unplanned lockdown has jolted India like no other country… After the pandemic hit, (the government) never bothered to track job loss or loss of lives of migrant workers, millions of whom walked home for months – a phenomenon not witnessed anywhere else in the world – some perishing on the way. Consequently, it did not do anything to protect jobs, unlike the OECD countries which saved 50 million jobs, or help survive loss of jobs and livelihoods of millions. In a display of gross callousness, it told the Parliament during the September 2020 session that it has no data and therefore it can’t even provide compensation for deaths of migrant workers,” Mohanty wrote.

The shocking truth is that at almost every stage of this still unfolding and, for the most part, avoidable tragedy, instead of alleviating a hapless public’s misery, the government’s actions (and inaction) actively contributed to it. It is precisely this lack of concern or competence, combined with institutional denial of the problem, as reflected most recently in the PM’s Independence Day speech, that should worry us as India’s hunger pandemic grows, with almost no sign of a reversal in sight.

[1] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/10/21/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-global-extreme-poverty/

Related posts:

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 21st, 2021

August 21st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: