The adoption of the so-called “Chips Act” in the USA in August of this year, with the addition of the word “science” in the title (not accidentally, as will be discussed below), is an extremely noteworthy event from many different perspectives. And, perhaps most of all, from a political perspective. It is from this latter perspective that the Chips and Science Act 2022 is mainly discussed.

For the very fact of its adoption was yet another strong indication of the validity of the long-held assumption that the globalization project was being scrapped. This project was launched with the end of the Cold War, when it seemed that the lines dividing the world socio-economic organism had finally disappeared. It was then that the philosophical utopia of the “end of history” was reincarnated, with the so-called “Washington Consensus” almost as its main applied component.

However, the emergence of China as a second world power by the end of the 2000s was perceived by Washington as a major challenge to its claim to leadership in all aspects of “post-history” humanity. The consequence of this perception was a “renewal” of the historical process with its inherent competition between the major power centers of the moment.

The main component of the category of “power” itself is now the level of economic development of the country claiming to be one of its main “centers” of concentration. China’s acquisition of its current political position on the world stage was ensured by the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative, a global project. Washington’s realization of the inadequacy of the “missile-aircraft carrier-strike” argument in countering this process has led to attempts to form “something global-economic of its own”.

These attempts are comprehensive, i.e. aiming to form inter-state structures designed to address both broad economic tasks and rather specialized ones. What both have in common is a well-defined anti-Chinese agenda. An example of the former is the recently established Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), whose 14 participants held their first ministerial meeting in early September.

As for the latter, the Chip 4 project, to which the Chips and Science Act under discussion has a direct bearing, is of particular importance today. The Chip 4 configuration, which is currently undergoing inter-state negotiations, and the above law are intended to solve a rather narrow, but crucial task for Washington at the current stage of its confrontation with Beijing. This boils down to the need to form an international structure designed to ensure the entire production cycle of semiconductors (“chips”).

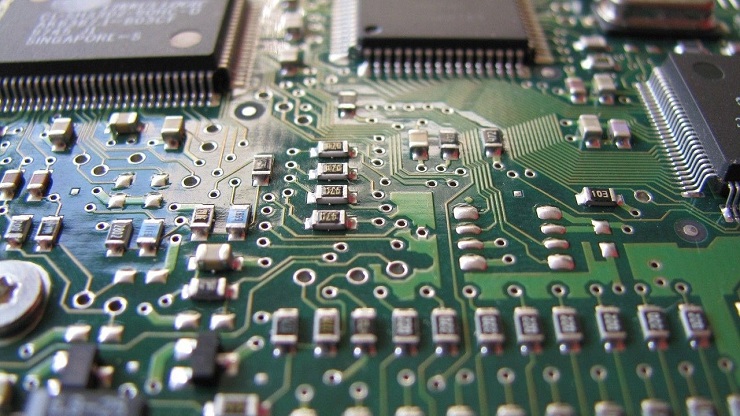

The latter, in turn, form the basis for the production of a wide range of IT end products, among which those used for military applications are of particular importance. It is no great exaggeration to say that the quality of modern weapon systems today is largely determined by the characteristics of the IT equipment used in them and, consequently, by those very chips.

This fact substantially determines the twofold nature of the above-mentioned task, according to which the Chip 4 configuration must be formed without China and against China. The same “anti-Chinese spirit” pervades the Chips and Science Act.

Such a task cannot be accomplished without violating the basic rules of international trade as spelled out in the WTO constituent instruments. Meanwhile, such violations are seen not only in China’s exclusion from the emerging international chip production chain, but also in the preferential government funding of US companies themselves, as well as the scientific institutions that are involved in accomplishing this task.

In the end, the total financial support for the package of measures spelled out in the Chips and Science Act was a whopping $52.7 billion. It increased as the range of problems to be solved grew and the need for extensive research was recognized. This explains the appearance of the word “science” in the title of this act.

The situation with its adoption is accurately depicted by an illustration in the Chinese newspaper Global Times article commenting on the set of problems involved. The text also gives another image in the form of a group of people who find themselves in the same boat, dangling in a stormy sea. The only way to escape is only through the coherence of the entire “crew,” and not through attempts to isolate some of its members.

However, the Chip 4 formation project envisages the latter. The backbone of this configuration should be made up of chipmakers from Taiwan, the Republic of Korea, Japan and the US. In terms of competence in the field, this is roughly the order in which the countries participating in the (future) configuration are ranked today. Although the technology for making basic semiconductor elements and then using them in the production of end products using the children’s construction kit principle originated in the US.

But notorious outsourcing, with its search for skilled and cheap labor abroad, has literally “swept” chip production to other countries. Both the Chips and Science Act and the Chip 4 project can be seen as attempts to some extent to “win back” the process of manufacturing fleeing from the US, which is continually growing in importance. This is also (mainly) a national security issue.

A key role in the (future, to repeat) Chip 4 configuration is assigned to Taiwan, which accounts for between 60% and 80% (depending on “packing density”) of chip production worldwide. Although the ROK and Japan have their own niche in chip production chains. And South Korea’s position on this configuration remains uncertain because Seoul is well aware of the possible costs of dealing with China because of the political (anti-Chinese) component present in the configuration. Meanwhile, Taiwan’s current leadership views its role in global chipmaking as an important tool that could be used as part of its overall course towards becoming a “common actor” in international relations. This course is increasingly supported by Washington, which fits in with the general process of aggravation of US-China relations.

Amid the media fuss over the very fact of the visit to Taiwan by Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the lower house of the US Congress, the practically meaningful component of the visit, which stemmed from talks she held with representatives of Taiwan’s semiconductor manufacturing business, went almost unnoticed.

The same topic of Taiwan’s (irreplaceable so far) role in the global chip industry was addressed in a wide-ranging interview by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken to the host of the popular television program 60 Minutes on September 25. In particular, it was said that although the US is keen to expand its own semiconductor manufacturing capabilities, in fact they are still largely made in Taiwan. In connection with the ongoing tensions in the Taiwan Strait, the “devastating” effects on the world economy of possible disruptions to the Taiwanese chip industry were predicted.

The same topic of organizing international (excluding China) chip production chains was the main practical content of US Vice President Kamala Harris’ trip to Japan and South Korea in late September, whose formal reason was attending the funeral of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Finally, it should be noted again that the main purpose of the Chips and Science Act is to increase the role of the US industry itself in semiconductor manufacturing with the apparent impossibility of full autonomy in this area from the partners in the (potential, to repeat) Chip 4 configuration.

Vladimir Terekhov, expert on the issues of the Asia-Pacific region, exclusively for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook.”

Related posts:

NASA rover on target for August landing on Mars

Ocean's Salt Measured from Space

Dino Dealer Says He's Not a 'Smuggler,' Calls Fossil 'Political Trophy'

Masking Returns Despite The Science, Illegal EUA & Zelensky Arrests Opponents/Shuts Down All Media

No more polygamy & underage wives for immigrants, says German minister

Busy Sunspot Unleashes Another Strong Solar Flare

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 13th, 2022

October 13th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: