Scientists have published fascinating new research into the reliefs found within the Chapel of Hatshepsut, an ode to the 5th pharaoh of the 18th dynasty who ruled between 1479 and 1458. Each of these whopping 13-meter reliefs, was painstakingly documented over the last decade, in order to understand the working relationship between a master and their apprentice.

Mirrored Reliefs at the Chapel of Hatshepsut

Located in the compound of the massive Temple of Hatshepsut, the Chappelle Rouge or Red Chapel, features these mirrored reliefs of a procession that is bringing offerings to the pharaoh. There are 200 figures, who are all bearers bringing the offerings, along with her offering menu, and a huge enthroned Hatshepsut in the middle, sitting grandly.

The Temple of Hatshepsut seen from the fields by the Nile. (Maciej Jawornicki / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

The study of the reliefs in the Chapel of Hatshepsut was conducted within the Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Expedition to the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari . The work was carried out on behalf of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology (PCMA), University of Warsaw, in cooperation with the authorities of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. It was led by Dr. Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska from the University of Warsaw, who is a specialist in the field of human sciences, particularly that of Egypt’s culture and history.

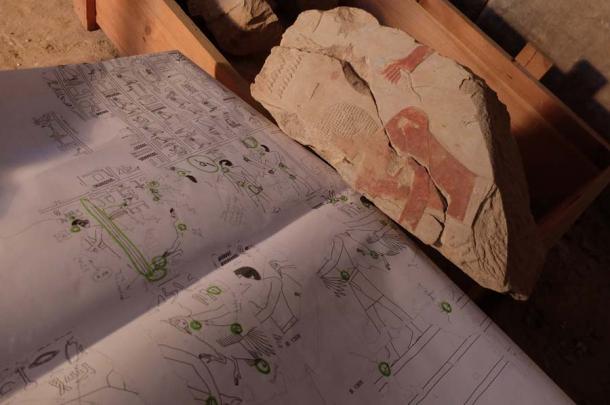

“The method was to render the wall surfaces at 1:1 scale on plastic-film sheets attached directly to the walls. These were then scanned and processed as vector graphics,” explained Dr. Stupko-Lubczynska. “I couldn’t stop thinking our documentation team was replicating the actions of those who created these images 3,500 years ago. Like us, ancient sculptors sat on scaffolding, chatting and working together.”

Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska verifying the drawing documentation in the Chapel of Hatshepsut. (Aleksandra Hallmann / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

Chaîne Opératoire or the Operational Sequence

Dr. Stupko-Lubczynska has astutely commented on a rather specific cultural anomaly that has posed a problem with reconstructing ancient Egyptian art and architecture. While artists were revered in places like ancient Greece, this was not the case with ancient Egypt, where “claims of authorship are particularly non-existent.”

In addition to this, Egyptian artists worked in community workshops, which prevented the individualization of styles and even prevented historical documentation about apprentices. She elucidates how, in the field of archaeology, the study of techniques and sequencing in a bid to produce the final product or artifact, is called the chaîne opératoire or the operational sequence.

Putting the loose blocks into the correct place within the Chapel of Hatshepsut walls. (Maciej Jawornicki / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

While derived from anthropology, in this particular context, it helps us understand the prevailing technological and socio-cultural environment which allowed and facilitated the creation of such work. It is particularly useful for relief work, because like lithic work, it is a process of reduction, and this concept has been applied to the reliefs in the Chappelle Rouge .

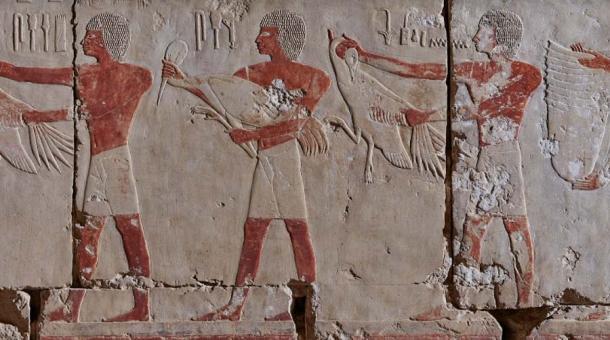

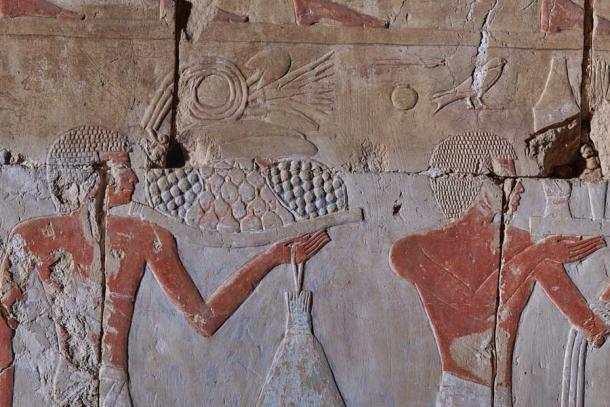

Built on the west bank of the Nile, the room was constructed using limestone blocks and decorated in raised relief. Two-thirds of each wall occupied with male bearers carrying offerings for (and to) the deceased. What was particularly noteworthy was the repetition of these figures, 200 in total and 100 on each lateral wall, in an amazing state of preservation.

Putting the loose blocks into the correct place within the Chapel of Hatshepsut walls. (Maciej Jawornicki/ Antiquity Publications Ltd )

The Preparatory Process and the Apprentice-Artist Liaison

“The chapel’s soft limestone is a very promising material for study, as it preserves traces of various carving activities, from preparing the wall surface to the master sculptor’s final touches,” said Dr. Stupko-Lubczynska.

She detailed a seven-step process, which is preserved in some form on the walls of the chapel:

- 1. Smoothing the wall and plastering of defects in the stone and joints between blocks.

- 2. Division of the wall surface into sections and application of a square grid.

- 3. The preliminary sketch is drawn in red paint, copied from a pre-prepared drawing.

- 4. Correction of the sketch by a master artist, who also added details in black paint.

- 5. Any text to accompany the images was inscribed.

- 6. With all the outlines done, the sculptors started their work, following the black lines.

- 7. The finished relief surface was whitewashed and colored.

Relief decoration in the Chapel of Hatshepsut, detail. The relief’s workmanship looks homogenous despite the fact that several sculptors were involved in its creation. (Maciej Jawornicki / Antiquity Publications Ltd

Searching for Clues About the Master Apprentice

During the project, her attention was drawn to the mystery of the master-apprentice. Who painted what and how? What was the level of skill identified for each role? One similarity with the Renaissance was found, in that those with lesser experience worked on the easier sections, such as torsos and limbs, while the more experienced artists paid attention to detail, including faces, as well as correcting any mistakes made by the apprentices.

After this, both would work on the wigs together, giving the lesser artists a chance to learn and collaborate with those more experienced and skilled. Apprentices were challenged to match the level of the artist, and Dr. Supko-Lubczynska defines this as modern-day “on the job-training”! However, this was not always successful. During her research, she found a half-finished wig because the apprentice failed to do his part.

Two offering bearers in the Chapel of Hatshepsut. The workmanship of their wigs indicates two sculptors working side by side, an apprentice (figure on the left) and a master (figure on the right). (Maciej Jawornicki / Antiquity Publications Ltd )

What Was Standard Practice? Deviating from the Norm

Though she keenly tried to gauge some kind of an individual streak in this work, it was to no avail. Artists worked towards creating a sort of homogenized work that matched Egyptian style masking all signs of individuality.

It was possible, however, to gauge that different works of art had different crews working on them. Each of the mirrored reliefs, for example was made using an inadvertent differentiation. One on the south wall is a jug made of clay, while the other is made of metal.

There was deviation from standard practices too, evidenced in hieroglyphic inscriptions near the wigs which seemed to have been added later, indicating that the sculptors began their work first in this place, and not the other way round which was the norm.

Dr. Stupko-Lubczynska’s research into the Chapel of Hatshepsut has shed light on the lack of individuality in ancient Egyptian culture, particularly in the spheres of art and architecture. The clues left behind within this ancient relief, provide a glimpse into the creation process, standard practices, the allocation of roles and the complex nature of the relationship between an apprentice and his master in ancient Egypt.

Top image: Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska documenting reliefs in the Chapel of Hatshepsut. Source: Agnieszka Makowska / Antiquity Publications Ltd

By Sahir Pandey

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 17th, 2021

November 17th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: