Consider the phenomenon known as “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.”

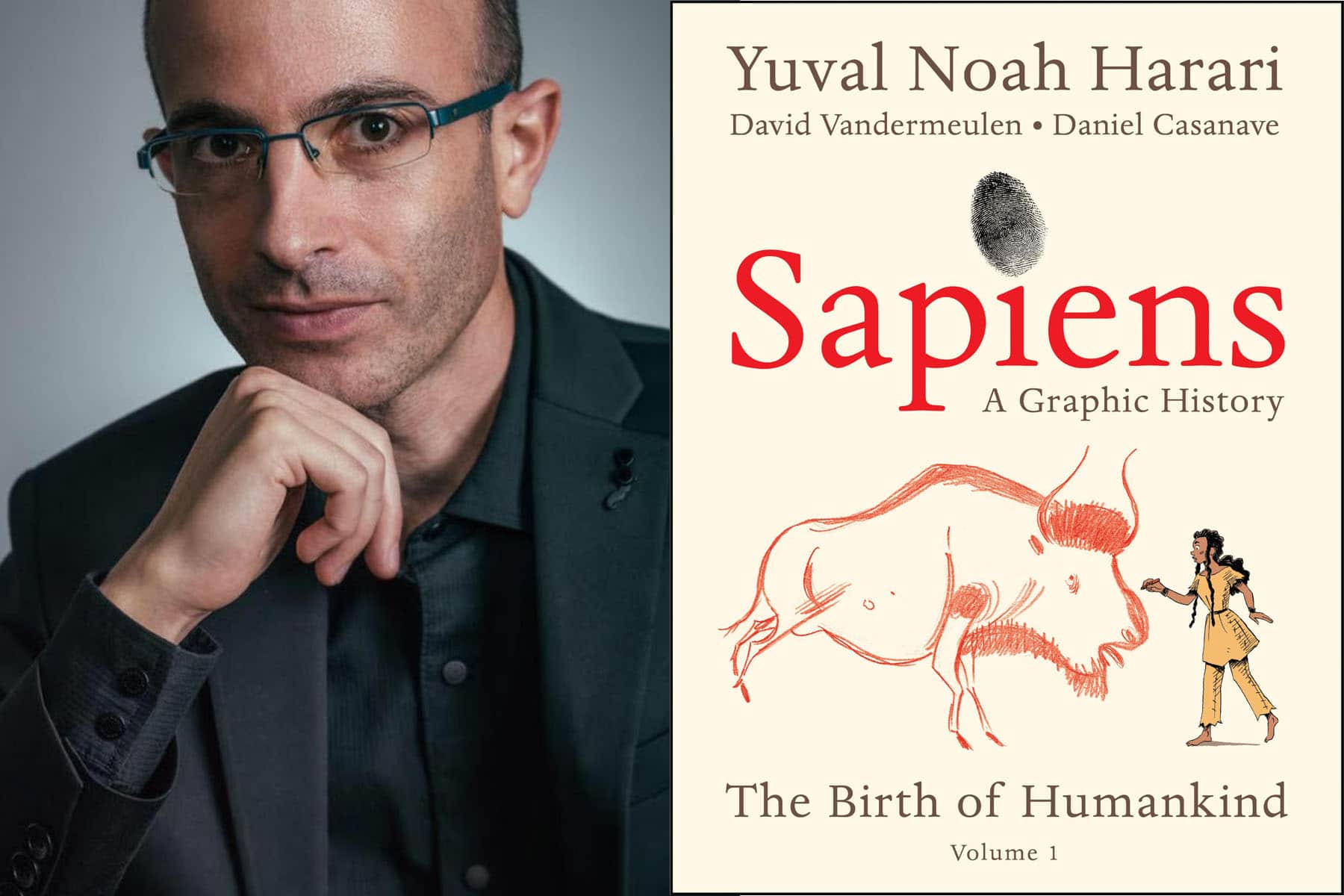

First written in Hebrew and self-published in Israel in 2011, the book by Yuval Noah Harari found an American publisher in 2014, quickly became an international best-seller in 60 languages, and then morphed into a kind of multi-media empire called Sapienship. Its visionary author, a history professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, is now a much sought-after public intellectual, and his career is managed by his husband, Itzik Yahav. When Fareed Zakaria asked Barack Obama what he was reading during an interview on CNN, the President sang the praises of “Sapiens.”

Harari is a gifted writer, and he is not afraid to traffic in the biggest of Big Ideas. He starts by reminding us that Homo sapiens, the last surviving species in the genus known as Homo, started out as unremarkable animals “with no more impact on their environment than baboons, fireflies or jellyfish.” Our unique gift among the other fauna, which emerged about 70,000 years ago, is our ability to imagine things that cannot be detected by the five senses, including God, religion, corporations, and currency, all of which he characterizes as fictions. He points out that we have risen to the top of the food chain only by exploiting and often exterminating other animals, but he predicts that humans, too, are not long for the world. All of these intriguing ideas – and many more — are explored in depth and with wit and acuity in “Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind.”

The latest manifestation of the “Sapiens” publishing enterprise is “Sapiens: A Graphic History” (Harper Perennial), a series that tells much (if not all) of the same sweeping saga in comic-book format. The first volume in the series, co-written by David Vandermeulen and inventively illustrated by Daniel Casanave, is “The Birth of Mankind.”

The first lines of the graphic novel version of “Sapiens” echo the original book, which starts with an alternate version of Genesis: “About 14 billion years ago, matter, energy, time and space came into being in what is known as the Big Bang.” The cartoon character who is shown to speak these lines is a caricature of Harari himself, comfortably seated in an armchair while floating in space at the moment of creation. And he continues to play the role of kindly schoolmaster throughout the rest of the book, peering into or entering the comic-book frame and sharing the story-line with his young niece, Zoe, an endearing Indian scientist named Arya Saraswati, and Professor Saraswati’s mischievous pet dog.

It is beyond argument nowadays that the comic book can be enjoyed by adult readers, and some of them are literally so graphic that their intended readers are adults only. “Sapiens: A Graphic History,” however, is child-friendly. For example, when explaining the principle that animals from different species may mate but cannot produce fertile offspring, Harari shows us a horse and a donkey and comments that “they don’t seem to be that into each other.” While many of the illustrations and dialogue bubbles are quite frank, the book serves as a useful primer of history and science for readers of all ages.

The illustrations, too, enliven the story-telling. Casanave wittily alludes to iconic artwork ranging from “American Gothic” and “Guernica” to the Flintstones and “Planet of the Apes.” To illustrate how the discovery of fire resulted in a diet that made human beings healthier, he depicts an idealized male couple standing together over a cooking pot: “Beautiful brain! Perfect smile! Six pack abs! Flat tummy!” The imagery is always cheerful and often funny, which is sometimes at odds with the dialogue bubbles, where the brutality and bloodlust of Homo sapiens over the course of history are described with candor.

Indeed, the graphic novel version of “Sapiens” lacks none of the edginess of the original. “Tolerance isn’t a sapiens trademark,” we are reminded. “In modern times, just a small difference in skin color, dialect or religion can prompt one group of sapiens to exterminate another. Why should ancient sapiens have been any more tolerant? It may well be that when sapiens encountered Neanderthals, history saw its first and most significant ethnic-cleansing campaign.”

The single most subversive idea in “Sapiens” is the notion that Homo sapiens achieved a great leap forward in evolution because of our unique ability to use language to “invent stuff.” Among the examples that Harari uses is religion: “You could never convince a chimpanzee to give you a banana by promising him unlimited bananas in ape heaven” is my single favorite line from “Sapiens,” and it’s in the graphic version, too, along with an illustration of a chimp descending Mount Sinai with a pair of tablets in his arms. The story is told, suitably enough, by an imaginary superhero called Doctor Fiction.

The single most subversive idea in “Sapiens” is the notion that Homo sapiens achieved a great leap forward in evolution because of our unique ability to use language to “invent stuff.”

“All large scale human cooperation depends on common myths that exist only in peoples’ collective imagination,” Doctor Fiction sums up. “Much of history revolves around one big question…how do you convince millions of people to believe a particular story about a god, a nation, or a limited liability company?” History proves that human beings have been perfectly willing to embrace the stories that other human being made up, and “now the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depend on the good grace of imaginary entities, almighty gods, or Google,” as Harari’s comic-book avatar puts it.

The graphic novel ends on a gloomy note. A tough cop named Lopez enlists Harari and Professor Saraswati to assist in the investigation of what she calls “the world’s worst ecological serial killers.” Says the cop: “Wherever these guys go, a whole bunch of bodies always show up.” By now, of course, we know the prime suspect is, as one character says, “all of us.”

Some of my favorite stuff in “Sapiens” is necessarily left out of the first graphic novel, but the author promises to tell the whole story in future titles in the series. In the meantime, of course, there’s always the original book to read, and I’ve gone back to my copy countless times already.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 2nd, 2021

January 2nd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: